Introduction

In March 2020, comics and pop culture media outlets in the US, like The Beat, Bleeding Cool, and Comic Book Resources, began reporting how the COVID-19 pandemic was having a devastating effect on the US comics industry. Diamond, the main comic book distributor in the US, shut down (Geppi, 2020). Major US comics publishers instituted work stoppages and laid off scores of employees (Johnston, 2020). Cons got canceled (McMillan, 2020). Comic shops struggled to stay afloat (Connolly, 2021).

At the same time, comic creators used their skills to illustrate personal experiences with the pandemic (Callender et. al, 2020); to address political dimensions of it (Buck, 2021); to serve as an outlet for healing from trauma and anxiety (Heifler, 2022); to function as a resource for people living with mental illness (Mazowita, 2021) and for those studying illness (Diedrich, 2021); and to provide an outlet for creators to imagine the world after the it ends (Chute, 2020). Furthermore, creator-oriented communities grew or came into existence.

In this article, I focus on three such communities—Cartoonist Kayfabe, the Sequential Artists Workshop, and Comic Lab. I discuss how each community presents a different take on what it means to make comics and to be a creator, and how they use different practices to build community. Considering these perspectives and practices raises questions about long-standing divisions within the US comics industry and comics fandom, including the divisions among mainstream and alternative comics, and divisions between professionals and amateurs. Also, it raises questions about how comics studies scholars relate to nonacademic communities where comic creators develop and share practitioner knowledge.

My interest in these communities reflects my experience participating in them. I started making comics during the pandemic, and I got involved in each of these communities over the course of 2020 and 2021. Since then, I have begun publishing comics in nonacademic anthologies and various academic spaces (see e.g., Unger, 2023; Unger, 2022a). My interest also reflects my ongoing research on the social practices involved in building communities (Unger, in press; Unger, 2022b). Put another way, the overlaps and tensions among my identities as a comics fan, a comics creator, and an academic inform this work.

In this article, I draw from comics studies research that addresses how comics people–fans, creators, and publishers–comprise a community, or more accurately multiple communities. In doing so, I draw attention to scholarship that deals with the traditionally accepted fault lines among different groups of comics fans and areas of the industry. Also, I draw from research on how platforms promote nichification in cultural production. Bringing comics studies and platform studies scholarship together helps me reconceptualize comics culture as a landscape composed of many fandoms and industries. Next, I discuss how Lave and Wenger’s (1991) theory of communities of practice provides an analytical lens through which to focus on the values and practices at the center of online creator-oriented comics communities. To lay the groundwork for discussing three such communities that grew or emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic, I develop a broad picture of how the pandemic affected the US comics industry and various stakeholders associated with it. Following this overview, I profile each community. In the end, I depict these communities as part of a landscape. Noting that the description of this landscape is only partial, I raise questions about how additional work focused on creators could help comics studies scholars see the relationships among community, creator identity, and craft.

Defining Comics Communities

As Davies (2019 p. 3) notes in “New Choices of the Comics Creator,” the “theorization of comics and graphic narrative have tended to focus on readership rather than creation.” Davies draws a distinction between interpretive work that speaks to fans, critics, and academics, such as Scott McCloud’s (1993) Understanding Comics, and work that speaks to creators, such as McCloud’s (2006) Making Comics. Woo (2018 p. 38) extends Davies’ assertion by arguing that “most comics scholars work or were trained in departments of literary studies, and formal or narrative features of comic art have received more attention than their production, circulation, and reception.” As someone who creates comics and teaches students how to do so, Davies would like to see more scholarship on craft and comics pedagogy. On one hand, I heed his call, with particular attention to how creators develop their craft in relation to communities. On the other hand, my work also connects to scholarship on US comics fans and the industry in order to refine the term community as it pertains to the comics landscape.

I argue that comic creators locate themselves in several different communities rather than as part of one homogenous group. I begin with Pustz’s (1999) Comic Book Culture: Fanboys and True Believers. In his book, Pustz focuses on the comic shop as a space that brings together the two distinct groups of comics readers, namely mainstream fans and alternative fans. Each group coalesces around particular titles, artists, and/or publishers. The mainstream fans stick to publishers like Marvel, DC, and Image, which are dominated by superhero titles. The alternative fans read an array of titles that feature grittier, more adult, or even more mundane stories and artwork that would not fit with the mainstream publishers. For the most part, the two main groups overlap very little. Pustz (1999, p. 17) laments the divisions between them, and he fears that in the future each comic shop will have to choose a side, catering to only one of the two. In turn, this will shatter comics fandom, which he sees as “unified into a single culture.” In ending his book, Pustz (1999, p. 213) argues that future research on comic book culture will focus on “specific reading communities,” such as “homosexual readers” or “prospective creators.” I would add that research on comic book culture should also focus on specific creator communities as such.

Pustz’s work draws from interviews and observations that he conducted in the late 1990s, but the idea that US comics fandom can be divided into mainstream versus alternative camps has held sway with some comics historians, critics, scholars, and fans since the 1970s (Singsen, 2017). While this narrative might have held explanatory power decades ago, it is certainly more complicated today. Recent scholarship has challenged this narrative by interrogating some of its champions, such as The Comics Journal (Singsen, 2017), and by exploring the contemporary contradictions bound up in the terms mainstream and alternative (Woo, 2018; Singsen, 2014).

The terms aren’t particularly helpful in describing the current state of the US comics industry. In “Is There a Comic Book Industry?”, Woo (2018) draws from 2016 sales data on comic books and graphic novels to argue that the kinds of comics that can be identified as mainstream may be up for debate. As the data indicates, fans of publications by Marvel, DC, and Image, and the like continue to frequent comic shops. Meanwhile, alternative comics fans, manga fans, and fans of titles aimed at young readers often get their publications from bookstores. However, sales of “mainstream” graphic novels at bookstores and sales of “alternative” titles at comic shops are not insignificant. Pustz’s fear that comic shops would cease to be community spaces for all of comics fandom seem to have come to fruition (if comic shops ever played this role). As Woo makes plain, there is not a single unified comics industry in the US. There are many publishers and venues through which fans purchase comics, and there are transmedia properties spawned from comic books that draw various other industries and types of fans into the discussion. I would add that there is not a single unified comics fandom. There are many comics fandoms, and many physical and digital spaces where comics people interact and build communities. Together, these spaces constitute the comics landscape.

The argument for viewing comics as a landscape reflects research on how platforms, such as YouTube, Amazon, and Spotify, have shaped cultural production writ large. Poell, Nieborg, and Duffy (2022a, pp. 5–7) argue that platform companies create the market for cultural production, own the infrastructure on which such production occurs, and regulate practices for all parties who use their platform. These companies make money from and maintain control over every aspect of their multisided markets: they make money off creators, users, and advertisers and dictate how each group interacts with one another. Platforms shape, or even dominate, various industries, and scholars have begun analyzing their effect on the news media, free-to-play game apps, pop music, and fashion, among others (Poell et al., 2022b; Poell et al., 2017).

Recent research on the platformization of comics addresses the effects that some of these platforms have had on creators and fans. Kohnen, Parker, and Woo (2023) apply Poell, Nieborg, and Duffy’s (2022a) framework to San Diego Comic-Con (SDCC). They raise questions about what platforms look like outside strictly digital spaces and argue that SDCC represents one example. Kim and Yu (2019) examine South Korean webtoon platforms Naver and Kakao (formerly Daum). They argue that these platforms create an atmosphere where professionals and amateurs compete with one another in a “winner-takes-all” system of crowd-sourced labor (Nieborg and Poell, 2018, qtd. in Kim and Yu, 2019, p. 4). Most webtoon creators, whether professional or amateur, work for no or low pay on strict deadlines while also promoting their work to try to increase its popularity so that the platform will pay them (Lamerichs, 2020; Kim and Yu, 2019). Additionally, Lamerichs (2020) describes how webtoon platforms force new constraints on comics creators, such as designing comics for vertical scrolling online rather than designing the page layouts, spreads, and turns required by print comics publishing. Furthermore, creators often use metrics about their readers collected by the platform to make data-driven decisions in their comics storytelling.

When platforms become commonplace in an industry, it can result in what Poell, Nieborg, and Duffy (2022a, pp. 140) call nichification, or the “structuring of production and consumption by narrowly defined interest communities.” Undoubtedly, the many industries and fandoms that comprise the comics landscape are shaped by various platforms, including SDCC, webtoons, social media, etc. Considering this research, my work in this article might be viewed as a step in mapping the nichification of comics. While I focus on what makes each community distinct by discussing the practices I engaged in and observed, I inevitably address some of the ways that different technologies, including platforms, afforded and constrained these practices. Put another way, I attend to some of the ways that these technologies have shaped each community as a niche.

Considering Comics Communities as Communities of Practice

To identify and document some of the practices found in different online creator-oriented communities, I turn to Lave and Wenger’s (1991) theory of communities of practice. The concept refers to how a group of people with a common interest interact to share ideas, knowledge, and experiences pertaining to that interest. To do so, communities develop a set of practices through which members engage with one another and build relationships. These practices include developing a shared history, formal or informal ways of determining membership and status within the community, and methods and expectations for group interaction, among others.

For educators and researchers, Lave and Wenger’s theory has opened conversations about how people learn in nonacademic settings and raised questions about how these practices might apply to learning in the classroom (see e.g., Garner, 2021; Pane, 2010). Furthermore, it has helped those whose interests and work straddles fan communities, industries, and academe to consider how to share knowledge derived from one context in another context (see e.g., Garner, 2021). However, Lave and Wenger’s theory has met with criticism.

Some critics argue that the theory glosses over power dynamics within communities of practice and how community members with more financial and/or social power skew community practices (Roberts, 2006), or how a community member works outside the community to achieve personal goals because the individual has the resources and connections to do so (Kimble and Hildreth, 2004). Others argue that the theory gives short shrift to the role that technologies play in delimiting interactions among members, particularly online (Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, 2015). Still, these critics use the theory in their work investigating various communities because of its adaptability to many different contexts.

In a basic sense, a community of practice for comic creators focuses on community members’ shared interest in figuring out how comic books work and developing or refining one’s creative process. In these communities, comic creators develop their skills through observation, participation, and interaction with other members who have different experiences with and processes for creating comics. Once you move beyond this broad view and begin to look at each community’s practices, their distinct perspectives come into focus.

In this article, I profile three online communities of practice for comic creators, namely Cartoonist Kayfabe, the Sequential Artists Workshop, and Comic Lab. I construct these profiles from the perspective of a community member, or in academic parlance, a participant-observer. To do so, I draw information for these profiles from two to three years of interaction with other members. Additionally, I use information from websites representing these communities and from public conversations, such as posts to social-media platforms, to reflect on and supplement my experiences. I do not reproduce ostensibly private discussions that are protected by paywalls. In these profiles I address the following:

The community’s history

How the pandemic affected the community

How the community determines membership

Some of the ways that members interact with one another

How these practices come together to reflect a particular perspective on comics

I do not claim that these profiles represent the values and opinions of other community members. Still, creating these profiles has helped me see similarities and differences across these communities and to begin to envision these communities as part of a complex landscape for comic creators.

Critics may take issue with how I use Lave and Wenger’s theory as a framework to study communities from the perspective of a participant-observer, arguing that doing so inevitably foregrounds an “affective rather than a distanced intellectual stance” (Garner, 2021, para. 2.3). They might argue that such work is not research; it’s just vibes. Researchers who use ethnographic or autoethnographic methods are often met with skepticism from critics who “support binary logics valuing objective detachment over subjective involvement” (Garner, 2021, para. 2.3). As Garner (2021, para. 2) notes, such skepticism has dogged acafans for decades. Acafans occupy multiple, or maybe more accurately, hybrid identities as academics, fans, and/or industry professionals, and academics have debated whether their work at these intersections or in theorizing from this hybrid perspective constitutes a limitation or an advantage (Garner, 2021; Lee, 2021; Jenkins, 2012).

I would argue that this hybrid identity provides both. I acknowledge that the criticisms of Lave and Wenger’s theory and my methods have merit and that my work is necessarily limited. For example, I describe some of the ways that each community uses digital technologies including platforms, but I do provide an in-depth analysis of each technology (e.g., YouTube, Instagram, etc.). Also, I do not include information collected from other community members, relying largely on my own interpretation of online discussions and events. However, I argue that my identity as a comics fan, a comics creator, and an academic puts me in a unique position within and across these communities, and from this position I contribute to ongoing discussions in comics studies about how the practices of comic creators might better inform how we study and teach comics. Because the COVID-19 pandemic and public safety directives for self-isolation during the pandemic preceded my membership in these online creator communities, I begin my discussion by documenting how the pandemic affected the US comics landscape.

The Pandemic and the US Comics Landscape

To develop a broad overview of how the pandemic affected comics in the US, I approach this landscape as being composed of a network of distributors, publishers, comic shop owners, event organizers, academics, creators, and readers–all of whom might be fans. Doing so illustrates how different communities responded to the pandemic and begins to reveal how they shaped other communities. It teases out their interconnectedness. It also reveals some of the factors that might have helped creator-oriented comics communities flourish online.

In the US, the COVID-19 pandemic shook up the comics industry by bringing the traditional methods of print production and distribution to a grinding halt. This shake up radiated out from distributors to publishers, from publishers to their staff and freelancers, from publishers to comic shops and events, and finally, from shops and events to readers.

In response to safety concerns and stay-at-home orders, Steve Geppi (2020), CEO of Diamond Comics Distributors, announced that the company was putting distribution on indefinite hiatus. His announcement stated that Diamond would go on hiatus after distributing materials that had a 1 April release date. This date reflects the fact that Diamond’s distribution warehouse is in Olive Branch, MS, and Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves issued a shelter-in-place order for nonessential workers to take effect 1 April 2020 (Mississippi Emergency Management Agency, 2020).

With no way to distribute comics to shops, major US publishers implemented “pencils down” policies where they ceased producing new material and laid off many employees and freelancers (Connolly, 2021; Johnston, 2020). For example, Marvel laid off half its editorial staff while also stopping work on 15–20% of its titles in April 2020 (Thielman, 2020), and DC laid off approximately 25% of its workforce by August 2020 (MacDonald, 2020). Overall, “30% fewer new comic books were released by the major publishers in 2020” (Comichron, no date, para. 4).

With few new comics arriving in the early months of the pandemic and fewer titles published for the remainder of 2020, comic shops feared the worst, and many shop owners pursued several new tactics in order to stay afloat, including creating web stores and conducting live auctions via Facebook and/or YouTube as well as offering curbside sales and delivery services. Shop owners reported an uptick in sales of manga and back issues throughout the year (O’Leary, 2021).

As comic shop owners grappled with the pandemic so too did comics event organizers. Many comic cons canceled their face-to-face gatherings, from industry stalwarts like San Diego Comic-Con and Emerald City Comic Con to events focused on small presses and self-publishers like the Small Press Expo (SPX) and Cartoon Crossroads Columbus. Some moved online with limited offerings. For example, San Diego Comic-Con organized Comic-Con@Home, consisting of video presentations, an online exhibit hall, and an art show and masquerade on Tumblr (Romano, 2020). Others postponed their events until 2021 or later. For example, SPX didn’t convene again until September 2022. Finally, some cons have yet to return online or otherwise (e.g., the Denver Independent Comics Expo and Comic Arts Brooklyn).

With cons canceled, postponed, or shifted online, associated comics studies events were canceled or scaled down. For example, conference organizers canceled the 2020 Comic Arts Conference that coincides with WonderCon in April 2020, and the 2020 Comic Arts Conference at San Diego Comic-Con offered a limited number of video presentations as part of the Comic-Con@Home event. Additionally, the 2020 Comics and Popular Arts Conference that coincides with DragonCon offered a limited number of video presentations as the convention shifted online (Comics and Popular Arts Conference, 2020). As Woo, Hanna, and Kohnen (2020) note, Comic-Con@Home 2020 was wildly successful in the sense that many more fans were able to view panels online than would have been able to attend them in person during a regular year at the con.

Just as major publishers and comics events shut down, some comic creators kicked into high gear by exploring their experiences, feelings, and reactions to the pandemic in fiction and nonfiction comics, publishing much of this work online. For example, comic creators Simon Hanselmann (2020) and Alex Graham (2020) serialized fictional works on Instagram. These comics reflected or satirized people’s responses to the pandemic. Hanselmann posted installments of Crisis Zone from March through December 2020, and Graham started Dog Biscuits in June 2020 and finished it in January 2021.

Others created online venues that put comic creators in conversation with one another and with readers. Beginning in April 2020, Gabe Fowler, owner of Brooklyn-based Desert Island Comics, initiated Rescue Party. Also published via Instagram, Rescue Party features 9-panel comics from creators around the world that address Fowler’s prompt of “visualizing your ideal future, in a utopian world after we survive this moment” (qtd. in Chute, 2020, para. 1). Rescue Party published work steadily for the rest of 2020 and first half of 2021 but has published only a handful of strips since then.

Within months of the pandemic’s worldwide outbreak, publishers released comics anthologies. In July 2020, editors Dean Haspiel and Whitney Matheson released Pandemix: Quarantine Comics in the Age of ‘Rona, a 56-page digital comics anthology, as a benefit for the Hero Initiative, a nonprofit that supports comic creators. In November 2020, The Nib centered the seventh issue of their quarterly comics anthology on the pandemic (Bors, 2020). Additionally, they published several strips exploring different dimensions of the pandemic on their website and through their social media accounts. Also, during November 2020, the Arts Students League of New York digitally released This Quarantine Life: A COVID-19 Era Comics Anthology, featuring comics from 76 different creators (Walker and Follender, 2020). Later, Graphic Mundi published the print edition of COVID Chronicles: A Comics Anthology in February 2021 (Boileau and Johnson, 2021). The anthology features over 60 comics by creators around the world that detail personal experiences and fictitious accounts of people’s experiences during the pandemic through October 2020.

Despite the challenges posed by the pandemic early on, comic book sales in 2020 surpassed sales figures from 2019 (Comichron, no date). This upward trend in comics sales continued in 2021 with industry-trackers Comichron and ICV2 noting that comic and graphic novel sales skyrocketed past 2020 figures, from $1.28 billion in 2020 to $2 billion in 2021 (MacDonald, 2022). It seems that many comic lovers took social-distancing policies as an opportunity to catch up with their favorite creators, stories, and characters and to explore work that they had missed over the years. Additionally, many readers discovered comics and graphic novels during the pandemic, and both groups continued to buy and read comics after many states rescinded their social distancing protocols.

As some comic creators and readers kicked into high gear during the pandemic, online communities for comic creators experienced a boom as well. Some communities that had already existed, like the communities around Cartoonist Kayfabe and Comic Lab, saw their numbers steadily increase over 2020 and 2021. Other communities, like the Sequential Artists Workshop shifted online to keep going as their states issued shelter-in-place and limited capacity protocols for physical spaces.

In the sections that follow I profiles of these communities, using the criteria described previously: their histories, how they navigated the pandemic, their structures and practices, and how they depict what comics are and can do (See “Considering Comics Communities as Communities of Practice”). Focusing attention on some of these communities sheds light on an underreported aspect of the US comics landscape: how the pandemic affected creator-oriented communities and how these communities work.

Cartoonist Kayfabe–The Collectors

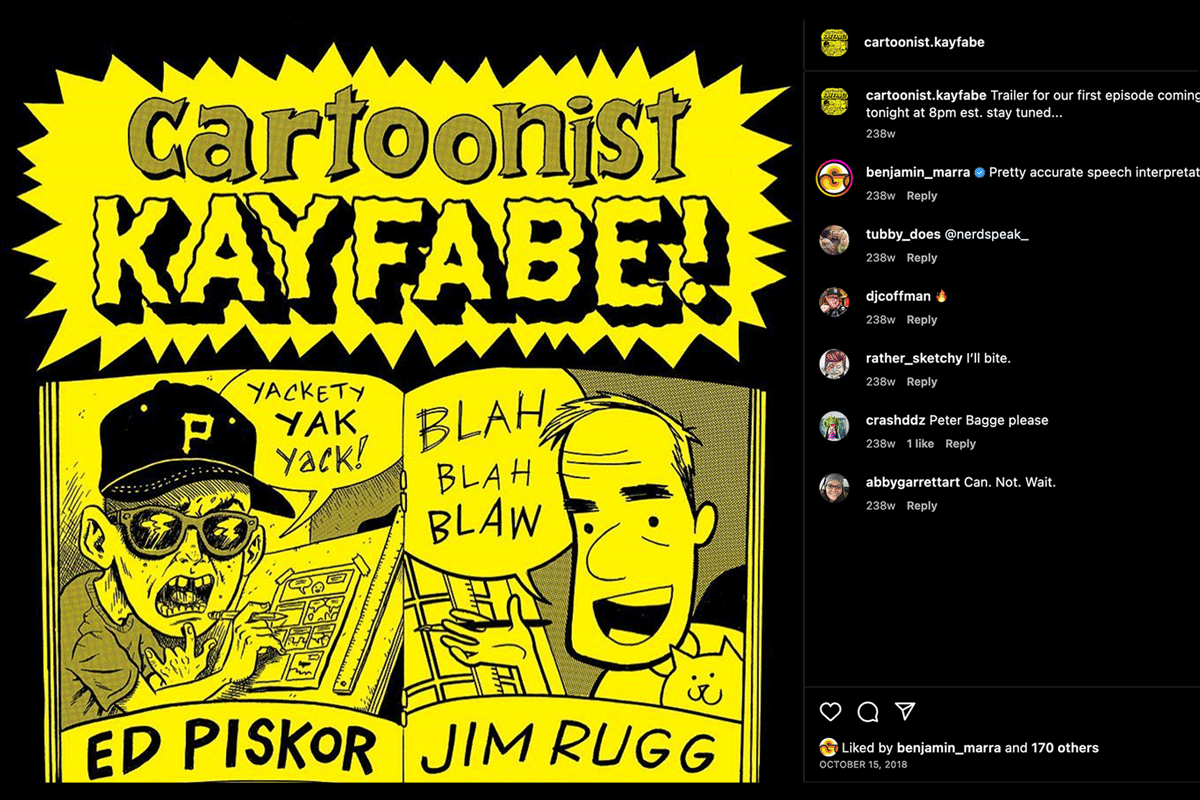

In October 2018, Pittsburgh-based comic creators Ed Piskor and Jim Rugg started the Cartoonist Kayfabe (CK) channel on YouTube (CK, 2018a) (see Figure 1). Piskor may be best known as the creator of Hip Hop Family Tree, Red Room, and X-Men: Grand Design, and Rugg is the artist on Street Angel, The Plain Janes, and the creator of Hulk: Grand Design, among others.

CK’s first Instagram post features the logo used across their social media platforms (CK, 2018b).

Piskor’s and Rugg’s careers traverse different areas of the US comics landscape as Pustz described it: they both have published “alternative comics” via small press and indie comics companies and have worked on “mainstream” superhero titles with major US publishers. Likewise, the content on their channel deals with a variety of comics. In these videos, Piskor and Rugg flip through a comic book or graphic novel on camera while they discuss things like the art style, panel composition, page layout, etc. The CK channel also features several other video genres, including interviews with a wide range of comic creators, such as indie comics darlings like Daniel Clowes, Adrian Tomine, and Ron Wimberly as well as 80s and 90s superhero comics purveyors like Rob Liefeld and Todd McFarlane. While Piskor and Rugg focus much of their attention on artists and artist/writers, the channel includes interviews with writers and editors as well, such as Ed Brubaker, Ann Nocenti, Shelly Bond, and Gary Groth. Typically, these interviews outline the interviewee’s career, focusing on highlights and behind the scenes stories about the creation and production of particular works. Oftentimes, these interviews include discussions of craft, process, and the tools the interviewee uses in their work. In addition to the flip throughs and interviews, CK features comics mailbag videos where Piskor and Rugg show off work sent in by viewers, video reviews of comics publications like old issues of Wizard and The Comics Journal, videos about comic conventions, and videos about the hosts’ comics making processes. Currently, they publish new videos daily.

CK has grown by leaps and bounds since Piskor and Rugg started it, attracting much of its audience after US politicians issued pandemic stay-at-home orders in March 2020. In April 2020, the channel had 15,000 subscribers (CK, 2020a). As of May 2023, that number sits at over 79,000 (CK, 2023a). Piskor and Rugg use the channel as well as the CK social media accounts to promote their work and to promote a love for comics in general. Through these venues, they interact with fans, who Piskor and Rugg refer to as Kayfabers. In addition to the mailbag episodes mentioned previously, Piskor and Rugg use fan-created artwork on the thumbnails for various videos, and they also post work by fans on the CK social media accounts. This artwork often depicts Piskor and Rugg as various comic book characters (see e.g., CK, 2022).

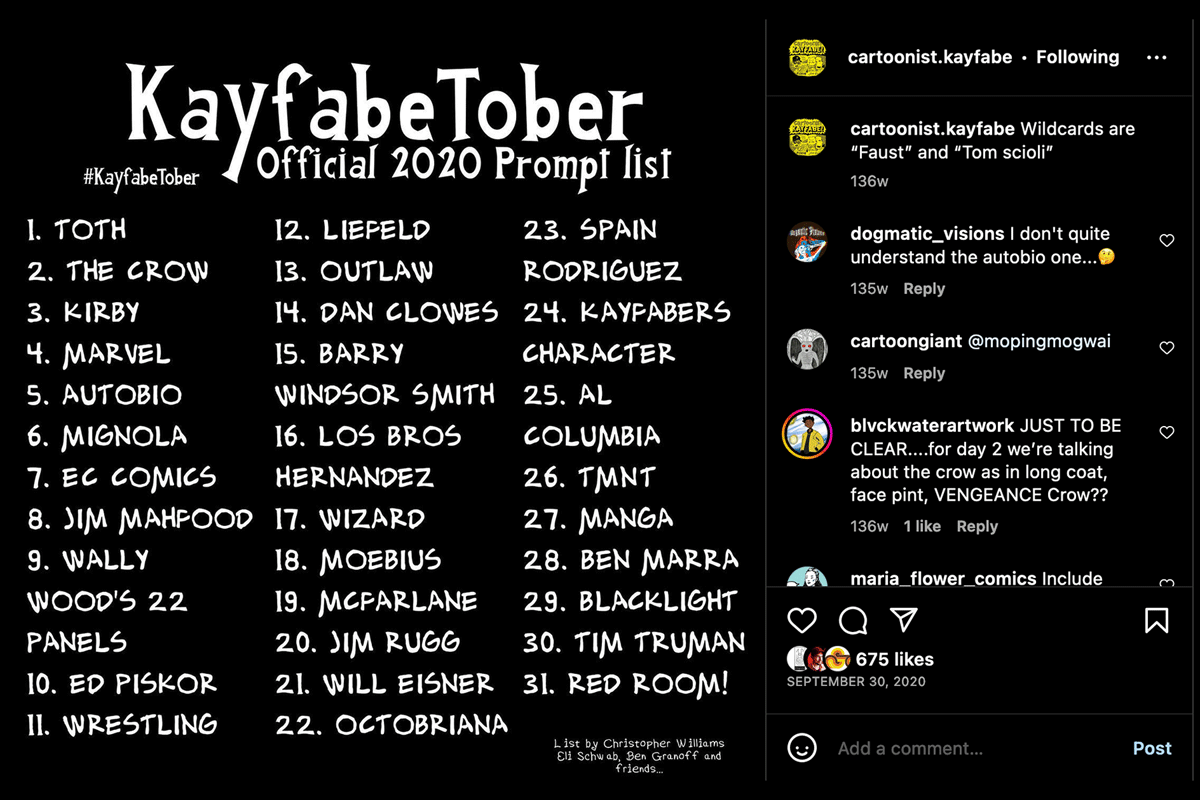

This attention to fans and use of multiple online platforms has helped CK establish a community around their channel. To foster more interaction, CK fans founded the Facebook groups Cartoonist Kayfabe Ringside Seats and Kayfabe Ringside Comics Swap, which have over 3400 and 883 members respectively as of 11 May 2023. Both groups are closed, and membership must be approved by community managers. Through the Ringside Seats group, CK fans discuss content from the channel, but they also discuss their own creative processes, promote their work, and collaborate on events and projects. For example, members of Ringside Seats organized and published a fanzine that included comics, interviews, reviews, and comics criticism called Wizerd in homage to Wizard: The Comics Magazine published 1991 to 2011 (Allen, 2020). The title is a nod to the CK YouTube channel’s origins as Piskor and Rugg started their channel with videos discussing issues of Wizard from the early 1990s. In addition to contributing to Wizerd, and submitting fan art, folks in the CK community participate in Kayfabetober, an online event that supersedes Inktober. Kayfabetober started in October 2020 (CK, 2020b) (see Figure 2). In lieu of random words used as prompts to create artwork, as in the Inktober annual event, Kayfabetober uses the names of well-known comic creators to spur participants’ creativity, pay homage to the medium, and to build community. For example, the 2020 list includes Piskor and Rugg alongside Alex Toth, Jack Kirby, Mike Mignola, and others. Kayfabetober continued in October 2021 and 2022. As of May 2023, there are over 10,000 #Kayfabetober posts on Instagram.

The Instagram post advertising Kayfabetober 2020 (CK, 2020b).

During the pandemic, CK filled a space that was missing when comic shops closed or functioned at limited capacity by following safety protocols. Because these protocols limited interaction, many people turned to the Internet to find the sense of community that comic shops had provided them previously. It may go without saying that for owners, employees, and customers, comic shops are not only spaces where fans can buy comics, they are spaces where people can geek out with one another over comics. This includes comic creators. CK stepped into that role. Several folks who participate in the Facebook groups own or work at comic shops, and there are frequent posts discussing members’ local comic shops. To show solidarity with the CK community, some comic shop owners and employees have created CK sections in their stores. These sections feature work by Piskor, Rugg, and Tom Scioli (another Pittsburgh-based comics creator who is a frequent guest on the channel) as well as any titles recently discussed in CK videos.

In terms of positioning the CK community as part of the comics landscape, I identify the Kayfabers as “the Collectors.” The collectors demonstrate a profound love of comics by collecting them and knowing or learning the creators’ and publishers’ histories. Major US publishing companies like Marvel, DC, and Image occupy a lot of space in this community, but CK also shows a penchant for the 1980s and early 1990s black and white comics boom in the US, manga and anime masters like Katsuhiro Otomo and Hayao Miyazaki, and outlaw comics (i.e., comics that feature over-the-top sex and/or violence, such as Faust and The Crow). This passion for collecting serves as the glue that connects Kayfabers, which is evident in examining the content from the YouTube channel and discussions in the Facebook groups. It is also demonstrated by the lists of artists included in the annual Kayfabetober event and through “Kayfabe effect.”

Coined by Piskor and Rugg, the Kayfabe effect refers to the fact that sales of comics and graphic novels tend to increase after the CK YouTube channel features the work. For example, in CK video from 29 June 2023 called “The Cult of the Comic Book 6.29.23,” Piskor and Rugg discuss the impact of a previous video that they produced about 93-year-old comics creator Robert Nunn (CK, 2023b and 2023c). In the 1970s, Nunn created a comic called Earthman, which he never did anything with. In the 1990s, his wife published it, and the couple sold copies through their local comic shop. In recent years, the coordinators of Power Comics tracked Nunn down and got permission to republish Earthman on their Floating World Comics imprint. After Piskor and Rugg told Nunn’s story on YouTube, sales of Earthman increased dramatically. In commenting on the Kayfabe effect, Rugg says, “To be able to hold [Earthman] up and say there’s a lot of interesting stuff in here, and then to have people go check it out, I love it. I don’t think of our primary purpose is to sell comics, but I am happy for every comic that we sell” (CK, 2023b, 4:51). Rugg’s comments illustrate that not only are Kayfabers comic collectors, but they lean heavily on guidance from Piskor and Rugg when looking to add to their collections.

If a creator identifies as someone who has collected comics for decades and has a room full of long boxes to show for it, then they will find a welcoming community in CK. Because this passion for collecting guides the CK community, it can outshine the fact that many Kayfabers create their own comics and that many of them make their living off comics as creators, shop owners, or employees. Still, CK video comments and Ringside Seats posts often address various aspects of the comics craft. In fact, the CK YouTube channel offers a “Make More Comics” playlist, which includes over a hundred videos with titles like “How to Make Comics the Gilbert Hernandez Way,” “Secrets Revealed: Richard Corben’s Color Technique Explained,” and “How to Ink Comic Books-90s Style” (CK, no date). These titles and the comments they generate reveal the CK community’s core values: paying homage to the work that community members grew up reading and using this work to inform one’s craft.

Sequential Artists Workshop–The Storytellers

While the Cartoonist Kayfabe community centers collecting as an important part of what it means to be a comics creator, the Sequential Artists Workshop (SAW) focuses on comics as a medium for expression. SAW members share a common desire to tell stories through comics and to improve on their storytelling skills. In addressing SAW’s history, this sense of building a community of storytellers working in the medium of comics comes to the fore.

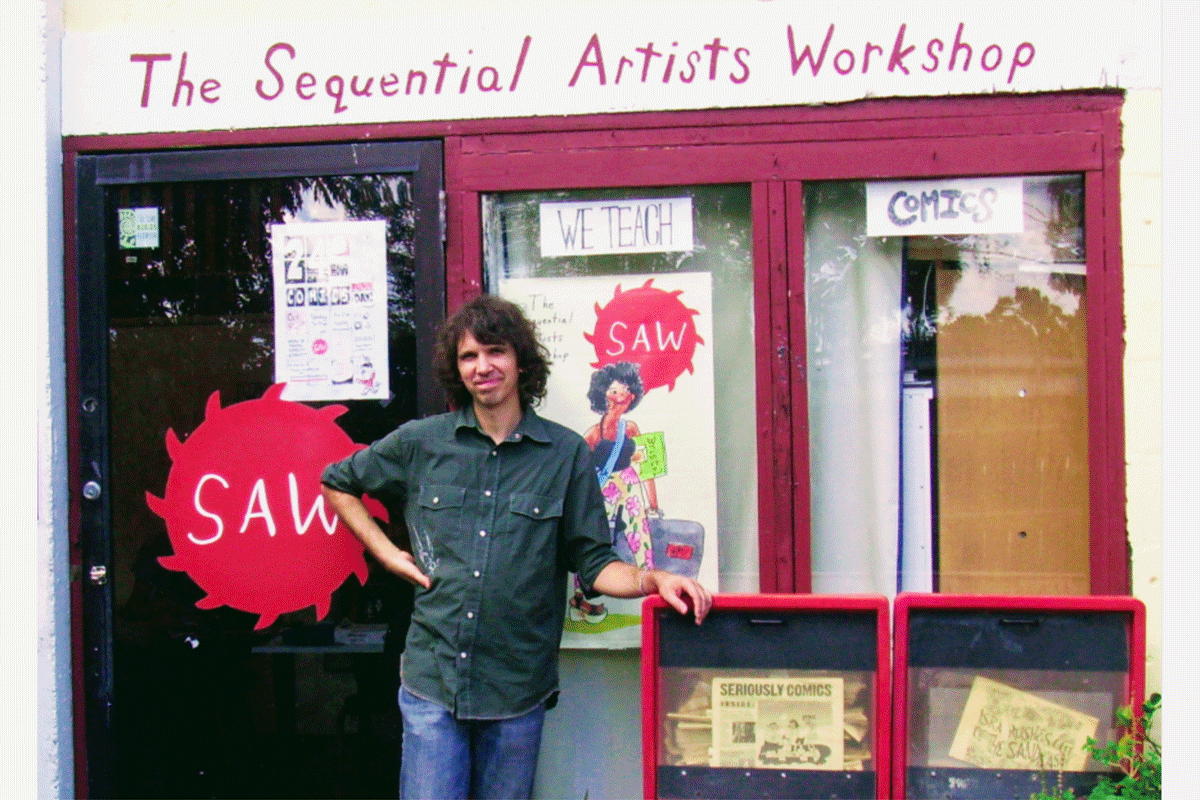

Tom Hart, the creator behind the Hutch Owen comics, Rosalie Lightning, and B is Dying, founded SAW as a 501c3 nonprofit in Gainesville, FL, in 2011. SAW opened its doors in January 2012 (see Figure 3). Hart’s goal was to create an alternative to the comics programs in expensive art schools: he wanted to establish a school “without the baggage, the loans or the politics of higher education” (Hart, no date, para. 1). In advertising posted to YouTube in October 2012, SAW billed itself as “a school, a studio space, a gallery space, and a publishing/promotional house for comics, graphic novels, sequential art” (SAW, 2012).

Tom Hart in front of the Sequential Artists Workshop’s brick-and-mortar space in Gainesville, FL in 2012 (SAW, no date a).

In the pre-pandemic years, SAW’s programming focused on face-to-face workshops, short courses, and a year-long intensive program. Typically, the workshops lasted one day or a few hours per day over the course of a few days, with time built into them for students to create comics. The short courses ran from 4–6 weeks, meeting for a few hours once per week, and students did the homework between class sessions. The year-long intensive program was broken into courses where students learned different aspects of the comics making process and about comics history. It culminated in a comic-length project that students displayed in an art show at the end of the academic year each spring.

In the months following the outbreak of the pandemic in the US, SAW pivoted toward online programming. Initially, they introduced a six-month graphic novel development intensive program beginning in June 2020. This GNI, as it is more commonly known, met online via Zoom every two weeks from June until December. Additionally, SAW offered monthly pro calls. On these calls, comic creators discussed their work and their comics-making processes. These pro calls featured creators such as Carol Tyler, Robyn Chapman, Matt Madden, and Leela Corman. In addition to these online meetings via Zoom, the GNI offered self-paced coursework and supplemental resources that divided the process of making a graphic novel into stages. The coursework covered topics such as outlining, scripting, thumbnailing, penciling, inking, and lettering as well as issues like getting stuck and dealing with burnout. As 2020 progressed and the pandemic continued, other programming, such as the workshops, short courses, and the year-long intensive, shifted online as well. For example, SAW added stand-alone, self-paced courses, like “Comics and Visual Storytelling for Writers,” “Let’s Make a Holy Book,” and “Storytelling Flow,” among others (SAW, no date b).

This shift from face-to-face programming in Gainesville to online programming helped SAW reach creators around the US and the world—both in terms of students and instructors. Some of these instructors included Tom Hart, Emma Jensen, and Jess Ruliffson, among many others. Many students who completed the six-month and year-long programs online wanted to maintain the sense of community that they had developed through their courses, so eventually SAW added membership tiers with monthly fees. These memberships allow folks to access old course materials, attend meetings to share their work, and attend upcoming pro calls.

SAW’s workshops, short courses, and six-month and year-long programs work on a sliding scale and aspects of SAW’s online space are free and open to the public. This space is hosted on Mighty Networks–an online platform that feels like a mashup of Facebook and a learning management system. Mighty Networks allows a user to be a part of multiple feeds, and when someone signs up for a course or for membership to a particular SAW group, they are granted access to additional feeds. For classes, these feeds are used to submit work in between class sessions and to engage in additional discussion. For membership groups, these feeds are used to maintain connections with alums from past classes and programs. Still, the free public feed is one of the most active on SAW’s network.

In addition to interacting on these feeds, SAW community members interact with one another through a weekly comics workshop on Friday nights called “We Believe in Comics” SAW took over hosting duties for these workshops from The Believer when the magazine shut down in spring 2021. Each Friday night, a different comics creator presents a themed workshop on Zoom. For example, Kristen Radtke hosted a recent workshop on “Making Comics about Secrets” (SAW, 2022). During these workshops, the host leads attendees through creating a short comic. Attendees share their comics with one another at the end of the session and on Instagram with the #FridayNightComics hashtag. As of May 2023, there are over 2100 Instagram posts that use the hashtag. Along with the free Friday night workshops, students host free weekly and biweekly events that anyone can attend. These groups have included a weekly session where folks work through Lynda Barry’s Making Comics, a weekly session of Procreate tutorials, and a weekly session on underdrawing and another on portraiture. There are also several free, weekly co-working sessions.

In terms of members, SAW’s online space attracts a wide range of creators, from school-aged children to retirees; academics and former academics from various fields such as art, writing, and English, among others; and professional artists and writers whose previous work employed other media. It also attracts many members with little formal training in art or writing. Furthermore, members’ backgrounds in comics and art differ along with their styles. Unlike my experiences with the CK community, I have encountered only a handful of SAW members whose penchant for comics includes the kinds of work published by Marvel, DC, and the like and carried in most comic shops. You won’t find many superhero comics posted to or discussed on SAW’s network or artwork that echoes the house styles associated with these publishers. SAW members work with traditional tools, digital tools, and any and everything in between. Because SAW attracts such a diverse range of creators, posts on SAW’s public feed might feel a bit scattered to newcomers. On any given day, you’ll find advertisements for upcoming meetings or courses, regular accountability check-ins (e.g., “Monday Goals,” “Where You’re at Wednesday,” and “Something Finished Friday”), advertisement for a creator’s finished work, discussions about the inspirations behind one’s work (e.g., “Thursday Non-Comics Inspirations”), etc. (see Figure 4).

If there is one aspect of comics that binds the SAW community together, it is the desire to tell stories through comics and to develop further as a comics creator. Overall, “storytellers” may be less concerned with collecting comics or creating comics as one’s profession than they are in developing their craft and building community through their work. They may also be less interested in engaging in the complexities of comics industries. While many folks in the SAW community have worked with various publishers, many more self-publish their work online or in print. Many SAW members distribute their work through Etsy and Gumroad, by posting their comics to Instagram, or by tabling at small conventions. Put simply, the SAW community values learning how to make comics, getting better at making them, and getting them out to readers in whatever form interests a particular community member.

Comic Lab–The Web Pros

While the CK community foregrounds collecting as being intertwined with creating comics, and SAW focuses on the craft of comics storytelling, the Comic Lab (CL) community devotes much of its attention to the business side of comics, particularly web comics. CL’s podcasts anchor the community while the real interaction among community members takes place on an affiliated Patreon account and a Discord server (see Figure 5).

A screenshot of the Comic Lab account on Patreon (CL, no date).

Cartoonists Brad Guigar and Dave Kellett host the podcasts. Both Guigar and Kellett are long-standing webcomic creators. Guigar is the cartoonist behind Evil Ink and Greystone Inn as well as the editor of webcomics.com, an online resource and community for web comic creators. He’s been creating webcomics since 2000. Dave Kellett is the creator behind webcomics Sheldon and Drive, and the co-director of the comics documentary Stripped. Kellett began publishing Sheldon online in 1998.

Guigar and Kellett release CL episodes every week through various podcast hosting sites. These episodes are free. In between these public episodes, they post weekly “pro tips” episodes for Patreon subscribers. Both the main podcast episodes and the pro tips episodes offer advice about being a comics creator and self-publishing. However, the types of advice on each podcast differ. Public episodes focus often deal with how current events affect various aspects of making, publishing, and promoting or marketing comics. For example, Guigar and Kellett have addressed how the pandemic affected comic creators over the past few years. Initially, they focused on issues such as how to manage time while working from home or how to write in times of grief (CL, 2020a). More recently, they have addressed the financial efficacy of tabling at cons as pandemic safety protocols loosen or disappear completely (CL, 2022; CL, 2021a). They have also discussed their opinions of various platforms for publishing and promoting comics, such as publishing through Substack and Webtoons (CL, 2021b; CL, 2020b). Meanwhile, pro tips episodes address pragmatic topics and issues of craft that change less dramatically in relation to current events, e.g., lettering and font choice or setting up a business bank account (CL, no date). Because of Guigar and Kellett’s backgrounds, discussions about publishing often focus on webcomics publishing. However, much of their advice can apply to comic creators working in any format.

CL reflects a part of the US comics landscape that often gets overlooked: webcomic creators who make a living off online publishing. In and of itself, however, the public CL podcast isn’t a community of practice because it does not provide a physical or virtual space where the hosts and listeners can interact with one another or share their work. While the public podcast addresses listener-submitted questions, there is little direct interaction between the hosts and listeners. The CL Patreon account affords more interaction, but this varies based on your membership level (CL, no date). At the lowest tier, it allows a member early access to episodes, to post questions and comments on Patreon below these episodes, and to access to the CL Discord server. At higher tiers, patrons have more access to Guigar and Kellett and the ability to shape the podcast’s content. These patrons can submit questions to be addressed on the podcast and attend livestreams, called “LiveGab,” when Guigar and Kellett record the episodes. The Discord server plays the most significant role in affording the kinds of interaction that build community, so unlike CK or SAW, folks must pay a fee to be a part of the CL community. In May 2023, the minimum fee is US$2 a month.

The CL Discord server offers several text channels for where members build community, such as #comiclab, #critiquecentral, #imadethis, #selfpromotion, #cspbootcamp, #protips, #writers_room, and #collaborations, among others. Discussing these channels gives some sense of how the CL community interacts in very specific ways. The #comiclab channel provides a general conversation channel. Posts may or may not relate to the content of podcast episodes. On #critiquecentral, folks post their work looking for specific feedback. Conversely, folks post their work to the #imadethis channel when they are proud and want to share it, but they are not looking for criticism. In #selfpromotion, folks share links to their comics on Webtoons, Tapas, and Instagram as well as links to their online shops or crowdfunding campaigns. On the #cspbootcamp channel, creators who use Clip Studio Paint ask others for advice about using the software. The #protips channel, like the #comiclab channel, may or may not refer to pro tips episodes. In #writers_room people address questions explicitly related to writing comics, of course. Finally, #collaborations is by far the least used channel on the server: the implication being that CL community members aren’t terribly interested in collaborating on comics.

By comparing CL’s Discord server to SAW’s network feeds and CK’s Facebook group, it becomes clear how the CL community differs from the others. In general, CL’s Discord server is like SAW’s network feeds in that interactions center on sharing one’s comics, looking for advice, or talking about craft or process. However, SAW also uses Zoom for several meetings and events, so SAW community members might have a better sense of who they are interacting with on a discussion feed than people do when interacting on a CL Discord channel. Also, discussions about comics as a business are rare on SAW’s feeds, but they are commonplace on the CL Discord server. It is relatively rare to see in-depth discussions about specific comics or graphic novels on the CL Discord server, unlike CK’s Facebook group or SAW’s feeds. These differences point toward CL’s focus on pragmatic issues. The Discord server has the character of a co-working space where community members interact when taking a break from their work. For the most part, CL community members seem to have a strong sense of what they are doing, but occasionally, they want advice from a colleague. For the CL community, comics are a profession, either one that members are already engaged in or one that they are working toward. Therefore, I refer to the CL community of practice as the “Web Pros.”

Conclusion

Taken together, the communities of practice that have coalesced around CK, SAW, and CL begin to reveal a complex landscape for US comic creators, a landscape further complicated but also made more visible by the COVID-19 pandemic. These communities point toward the kinds of support that some comic creators seek and that I needed in order to make comics during the pandemic (Unger, 2022).

For the collectors, comics are a life-long passion, and creating them connects one to a tradition. The goal for such a creator might be to become a part of this tradition but also to help shape it. During the pandemic, this meant that I returned to my long boxes and the proverbial back issue bin to pick up where I left off with a specific title or to find something new. It meant gravitating toward others who interpret US comics history through the lens of the comic shop, at least in part, and it meant considering craft as a tradition shaped over many decades and by specific creators.

For the storytellers, creating comics means developing the tools to tell one’s stories in engaging ways. Storytellers aren’t necessarily interested in creating comics as a profession. They are interested in creating work that resonates with readers. My experiences in this community of practice helped me focus on becoming a better comics creator by getting better at telling stories. During the pandemic, this meant I dove headlong into investigating comics as a medium by focusing on my own practice and that I finally got around to telling the stories that I had put off for years.

Finally, web pros focus on comics as something enjoyable but also as commerce. They’re determined to make their passion for comics the work that pays the bills. During the pandemic this might have meant exploring new avenues for income, stepping up their work to cover unanticipated expenses, or shifting more time toward comics in order to move from someone who makes comics as a hobby to someone who makes comics as a profession. For me, it meant publishing my first comics and shifting my research and teaching toward comics.

Being a member of these communities of practice does not mean that one must adhere to a singular concept of what it means to be a comics creator or to a simple idea of what comics are and can do. Comics can connect you to the history and traditions of an art form in a particular area of the world, they can present evocative stories that connect with readers, and they can make money. Sometimes, a lot of money. And, being a comics creator can mean dealing with the pull of all three perspectives, and others, throughout your time making comics. Therefore, creators might find it valuable to engage in several communities of practice where a community has coalesced around different perspectives.

Future work investigating communities of practice for comic creators in the US might delve deeper into CK, SAW, and CL by using different approaches to investigate community members’ experiences, such as conducting interviews, or by delving much more deeply into how platforms like YouTube, Instagram, Facebook, and others afford and constrain these communities. Additional research might focus on other communities of practice for comics creators, including other online or face-to-face communities. As Woo (2018, p. 40) reminds us, attempts to impose boundaries “on a fluid, complex field of social practices” are never innocent; they reflect particular “values, interests, and unexamined prejudices.” I note that while the communities I discuss in this article include members of various races and ethnicities, social classes, and gender identities and sexual orientations, they were established by white cis men, and I did little to address how inclusive these communities are to creators with historically marginalized or multiply marginalized identities. Future research might focus on questions of representation and inclusion by using different frameworks or by focusing explicitly on communities of practice created by and for people of color and/or LGBTQIA+ comic creators, for example, the Black Comics Collective or Prism Comics. Such research would contribute to a better understanding of the ever-shifting comics landscape in the US and a better understanding of how practitioner knowledge and craft connect to communities.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all the wonderful folks who I have met through Cartoonist Kayfabe, the Sequential Artists Workshop, and Comic Lab, particularly SAW’s Comics Expedition Group who have served as a sounding board for my own comics work. Thanks also to The Comics Grid reviewers for feedback on an earlier iteration of this article.

Editorial Note

This article is part of the Conjuring a New Normal: Monstrous Routines and Mundane Horrors in Pandemic Lives and Dreamscapes Special Collection, edited by Alexandra Alberda and Julia Round, with assistance from the editorial team.

Competing Interests

Since 2020, Dr. Unger has been a Patreon supporter of the Comic Lab podcast as well as a student-member of the Sequential Artists Workshop. He has not been employed by or taken payment from any of these groups or from Cartoonist Kayfabe.

References

Allen, TJ. 2020. The culture of comics: Cartoonists Kayfabe inspires ‘Wizerd’ fanzine. Previews World, 13 Oct. Available at: https://www.previewsworld.com/Article/241914-The-Culture-of-Comics-Cartoonists-Kayfabe-Inspires-Wizard-Fanzine. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Boileau, K, and Johnson, R. (eds.). 2021. COVID Chronicles: A Comics Anthology. State College, PA; Graphic Mundi. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9780271091723

Bors, M. (ed.). 2020. Issue 7: Pandemic. Portland: The Nib.

Buck, LE. 2021. Pandemic cartoons for the #Draw challenge: Sisyphus as key worker and The Toad and the Scorpion. The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship 12(1): 1–11. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/cg.6468

Callender, B, Obuobi, S, Czerwiec, MK, and Williams, I. 2020. COVID-19, comics, and the visual culture of contagion. The Lancet, 396(10257): 1061–1063. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32084-5

Cartoonist Kayfabe (CK). 2018a. Episode 1 trailer. YouTube, 15 Oct. Available at: https://youtu.be/k5fZtBb9yKs. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Cartoonist Kayfabe (CK). 2018b. @cartoonist.kayfabe Trailer for our first episode coming tonight at 8pm est. Stay tuned. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/Bo8t50zArmO/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Cartoonist Kayfabe (CK). 2020a. @cartoonist.kayfabe Subscribe to our YouTube and get us over the hump to 15,000. Link in profile. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/B_APRweJFce/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Cartoonist Kayfabe (CK). 2020b. @cartoonist.kayfabe Wildcards are ‘Faust’ and ‘Tom Scioli’. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CFxXP-Xh_X-/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Cartoonist Kayfabe (CK). 2022. @cartoonist.kayfabe Thanks @robgaughran for this portrait of the CK horror hosts. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CiZD0zTMWAf/. [[Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Cartoonist Kayfabe (CK). 2023a. @caroonist.kayfabe Subscribe to the YouTube channel if you dig our vids and get us to 74k! Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CnLG3QZvaL-/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Cartoonist Kayfabe (CK). 2023b. The cult of the comic book 6.29.23. YouTube, 29 June. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/live/ZO2R_AeqjFM. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Cartoonist Kayfabe (CK). 2023c. 93 year old cartoonist makes first comic in 50 years! True story! YouTube, 27 June. Available at: https://youtu.be/pPmcEFANlg0. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Cartoonist Kayfabe (CK). no date. Make more comics playlist. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLclmZ5KRrb89MP6y2BwPKNwhoVCzPkGUL. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Chute, H. 2020. Can comics save your life? Public Books, 21 Aug. Available at: https://www.publicbooks.org/can-comics-save-your-life/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Comic Lab (CL). 2020a. Episode 121: Comics under quarantine. Simplecast, 16 April. Available at: https://comiclab.simplecast.com/episodes/comics-under-quarantine. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Comic Lab (CL). 2020b. Episode 109: Should you build your audience on Webtoons? Simplecast, 23 January. Available at: https://comiclab.simplecast.com/episodes/should-you-build-your-audience-on-webtoons. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Comic Lab (CL). 2021a. Episode 190: Exhibiting at your first comic con. Simplecast, 12 August. Available at: https://comiclab.simplecast.com/episodes/exhibiting-at-your-first-comic-con. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Comic Lab (CL). 2021b. Episode 196: Will Substack change comics? Simplecast, 23 September. Available at: https://comiclab.simplecast.com/episodes/will-substack-change-comics. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Comic Lab (CL). 2022. Episode 242: San Diego Comic-Con review. Simplecast, 11 August. Available at: https://comiclab.simplecast.com/episodes/san-diego-comic-con-review. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Comic Lab (CL). no date. Patreon account. Available at: https://www.patreon.com/comiclab/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Comichron. no date. Comics and graphic novel sales hit new high in pandemic year. Available at: https://www.comichron.com/yearlycomicssales/industrywide/2020-industrywide.html. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Comics and Popular Arts Conference. 2020. 2020 Program. Available at: https://comicspopularartsconference.org/2020-program/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Connolly, S. 2021. COVID-19 impact on the comic book industry. News 2: NBC Affiliate, 19 Feb. Available at: https://www.counton2.com/news/local-news/covid-19-impact-on-the-comic-book-industry/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Davies, PF. 2019. New choices of the comics creator. The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, 9(1): 3. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/cg.153

Diedrich, L. 2021. Comics as pedagogy: On studying illness in a pandemic. The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, 11(1): 1–9. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/cg.7680

Garner, RP. 2021. Acafan identity, communities of practice, and vocational posting. Transformative Works and Cultures, 35. Available at: https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/1985/2771. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023]. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2021.1985

Geppi, S. 2020. Steve Geppi addresses coronavirus’ effect on distribution. Available at: https://www.diamondcomics.com/Article/241552-Steve-Geppi-Addresses-Coronavirus-Effect-on-Distribution. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Graham, A. 2020. @alex.graham.artist Dog Biscuits post 1. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CBjawMKjzWT/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Hanselmann, S. 2020. @simon.hanselmann Crisis Zone post 1. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/B9sB-C3hQ_X/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Hart, T. no date. Sequential Artists Workshop. Available at: https://www.tomhart.net/saw.html. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Haspiel, D, and Matheson, W. (eds.). 2020. Pandemix: Quarantine Comics in the Age of ‘Rona. LA, CA: Hero Initiative. Available at: https://www.heroinitiative.org/shop/books/pandemix-56-page-digital-download-comic/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Heifler, SP. 2022. Let me out of here: A story of using comics to heal during the pandemic. The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, 12(1): 1–11. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/cg.6545

Jenkins, H. 2012. Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. London: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9780203114339

Johnston, R. 2020. Marvel tells more comic creators to stop work for now. Bleeding Cool, 15 April. Available at: https://bleedingcool.com/comics/marvel-tells-more-comics-creators-to-stop-work-for-now/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Kim, JH, and Yu, J. 2019. Platformizing webtoons: The impact on creative and digital labor in South Korea. Social Media and Society, 5(4): 1–11. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119880174

Kimble, C, and Hildreth, P. 2004. Communities of practice: Going one step too far? HAL, Post-Print. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.634642

Kohnen, MES, Parker, F, and Woo, B. 2023. From Comic-Con to Amazon: Fan conventions and digital platforms. New Media and Society, 1–22. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231165289

Lamerichs, N. 2020. Scrolling, swiping, selling: Understanding Webtoons and the data-driven participatory culture around comics. Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies, 17(2): 211–229. Available at: https://www.participations.org/17-02-10-lamerichs.pdf. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Lave, J, and Wenger, E. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge UP. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Lee, K. 2021. Acafan methodologies and giving back to the fan community. Transformative Works and Cultures, 35. Available at: https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/2025/2859. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023]. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2021.2025

MacDonald, H. 2020. More layoffs at DC mark the end of an era. The Beat, 11 Nov. Available at: https://www.comicsbeat.com/more-layoffs-at-dc-mark-the-end-of-an-era/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

MacDonald, H. 2022. Report: Comics and graphic novel sales grew over 60% in 2021. The Beat, 30 June. Available at: https://www.comicsbeat.com/report-comics-and-graphic-novel-sales-grew-over-60-in-2021/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Mazowita, A. 2021. Graphic communities: Comics as visual and virtual resources for self and collective care. The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, 12(1): 1–8. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/cg.6493

McCloud, S. 1993. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. NY: Harper Perennial.

McCloud, S. 2006. Making Comics: Storytelling Secrets of Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels. NY: William Morrow.

McMillan, G. 2020. Seattle’s Emerald City Comic Con canceled. The Hollywood Reporter, 16 June. Available at: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/seattles-emerald-city-comic-con-2020-canceled-1298698/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Mississippi Emergency Management Agency. 2020. Governor Reeves Issues a Statewide Shelter-In-Place Order. 1 April. Available at: https://www.msema.org/governor-reeves-issues-a-statewide-shelter-in-place-order/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

O’Leary, S. 2021. 2020 was a tough year for comic shops. Publishers Weekly, 2 April. Available at: https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/comics/article/85976-2020-was-a-tough-year-for-comics-shops.html. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Pane, DM. 2010. Viewing classroom discipline as negotiable social interaction: A communities of practice perspective. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(1): 87–97. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.05.002

Poell, T, Nieborg, D, and Duffy, BE. 2022a. Platforms and Cultural Production. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Poell, T, Nieborg, D, and Duffy, BE. 2022b. Spaces of negotiation: Analyzing platform power in the news industry. Digital Journalism. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2103011

Poell, T, Nieborg, D, Duffy, BE, Prey, R, and Cunningham, S. 2017. The platformization of cultural production. In: Selected Papers of the Association of Internet Researchers 2017, Tartu, Estonia on 18–21 Oct. 2017, pp. 1–19.

Pustz, MJ. 1999. Comic Book Culture: Fanboys and True Believers. Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi.

Roberts, J. 2006. Limits to communities of practice. Journal of Management Studies, 43(3): 623–639. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00618.x

Romano, A. 2020. Comic-Con 2020 was entirely virtual—but was it still magical? Vox, 27 July. Available at: https://www.vox.com/2020/7/27/21332948/sdcc-comic-con-2020-at-home-online. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Sequential Artists Workshop (SAW). 2012. What is SAW comics? Sequential Artist’s Workshop. YouTube, 12 Oct. Available at: https://youtu.be/V4HkUBXmso8. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Sequential Artists Workshop (SAW). 2022. SAW comics workshop—Making comics about secrets with Kristen Radtke. YouTube, 2 Dec. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/live/vwC9a_EH97c?si=8qd6txy_6crZy_PA. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Sequential Artists Workshop (SAW). no date a. About. Available at: https://www.sequentialartistsworkshop.org/about-history. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Sequential Artists Workshop (SAW). no date b. Courses. Available at: https://learn.sawcomics.org/collections/courses. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Singsen, D. 2014. An alternative by any other name: Genre-splicing and mainstream genres in alternative comics. Journal of Comics and Graphic Novels, 5(2): 170–191. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2013.871306

Singsen, D. 2017. Critical perspectives on mainstream, groundlevel, and alternative comics in The Comics Journal, 1977 to 1996. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 8(2): 156–172. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2016.1247372

Thielman, S. 2020. ‘This is beyond the Great Depression’: Will comic books survive coronavirus? The Guardian, 20 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/apr/20/great-depression-will-comic-books-survive-coronavirus-marvel-cuts. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Unger, D. 2022a. Words and smiles: Making comics during the pandemic. The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, 6(2). Available at: http://journalofmultimodalrhetorics.com/6-2-unger. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Unger, D. 2022b. Free pride hugs. Community Literacy Journal, 16(2): 181–186. DOI: http://doi.org/10.25148/CLJ.16.2.010633

Unger, D. 2023. Memphis gay bars. Radical Faerie Digest, 193: 20–23. Available at: https://issuu.com/rfdmag/docs/rfd_193_7x10_online. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Unger, D. In press. Grassroots activism and tactical communities: Examining the Poor People’s Corporation in Mississippi in the 1960s and 1970s. In: M. Kimball and H. Sarat-St. Peter eds., Tactical Technical Communication.

Walker, S, and Follender, G. (eds.). 2020. This Quarantine Life: Comics Anthology. NYC: The Art Students League of NY. Available at: https://theartstudentsleague.org/this-quarantine-life-comics-anthology/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Wenger-Trayner, E, and Wenger-Trayner, B. 2015. Available at: https://www.wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].

Woo, B. 2018. Is there a comic book industry? Media Industries, 5(1): 29–46. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3998/mij.15031809.0005.102

Woo, B, Hanna, E, and Kohnen, MES. 2020. Comic-Con@Home: Virtual comics event declared a failure by industry, but fans love it. Available at: https://theconversation.com/comic-con-home-virtual-comics-event-declared-a-failure-by-industry-critics-but-fans-loved-it-143801. [Last accessed 17 Oct. 2023].