On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 (Covid) a national pandemic prompting many governmental efforts to contain the rapidly spreading virus. In response to the new virus, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) released information on social distancing, quarantine, and compulsory use of masks. California was the first state to issue a stay-at-home order on March 19, 2020, after which other states soon followed suit, thus beginning the first wave of nationwide lockdowns in the U.S. By May 28, 2020, only two months later, Covid deaths in the United States surpassed 100,000. Meanwhile, various states continued lockdown measures with services, businesses, and industries being restricted in efforts to curb this growing death rate. In the same month on May 25, 2020, George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis, Minnesota by a white police officer triggering a wave of Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests throughout the country. Within days hundreds of thousands of people swarmed the streets and dense crowds soon gathered in most major metropolitan areas throughout the country. Logically, Covid related infections spiked once again with the outpouring of the protests.

As the country, and then-President Trump, pushed to re-open the economy, by July 2, 2020, cases had spiked to 50,000 new infections per day, forcing many states to reverse their plans. Lockdowns with mask mandates continued to remain firmly in some states, while other states insisted on remaining open. By August 2020, now 6 months into lockdown, the mask mandate debates had begun. Although talks around masks had already been a pressure point for Americans, the continued mandates sparked outrage and cries of an overbearing government, while other groups of citizens felt the government was not doing enough in the easing of restrictions as infection rates continued to rise. By mid-2020, Covid had become the third leading cause of death in the U.S. Notably, as other countries delt with the pandemic some also juggled a beratement of natural disasters, such as the wildfires that devasted Australia and disastrous floods in Indonesia.

Starting from 2020 to the present time now in early 2023, many people experienced what is fair to refer to as years from hell, especially in the early stages of the pandemic when the most restrictive lockdown measures were in place. Many were forced indoors, cut-off from support systems, family, friends, and forced to rely on a government that was facing more than one social revolution. People lost jobs, layoffs were rampant as companies downsized, closed brick and mortars, or decreased employee salaries in droves. It was a time of chaos, isolation, distrust, and visibility.

There was no escape from the mundane horrors the pandemic introduced. Even the virtual realms of social media and other mobile technologies could no longer offer the shelter from reality many in society desperately seemed to be seeking. Technology became yet another source of nihilistic gloom and doom—leading to a prevalent increase in the cultural phenomenon of ‘doomscrolling’. Doomscrolling can be defined as ‘the phenomenon of elevated negative affect after viewing pandemic related material’ (Price et al. 2022) or phrased generally, acts of consuming endless streams of negativity online to the detriment of the scroller (Ytre-Arne and Moe 2021).

During these unprecedented and difficult times, people had to adjust their everyday routines and learn to adapt to a new normal initiated during this period. This paper will address the chaos of surviving the pandemic, how creatives used comics as an outlet to express their perspectives and experiences in this new normal, and how ‘doomscrolling’ has shifted the once euphoric representation of mobile technology into a place of despair and horror. This article will analyze the phenomenon of doomscrolling as it manifested in comics during the Covid pandemic amidst the contexts described above.

Comics during the Pandemic

Since many people spent more of their time cooped up inside their homes and cutoff from traditional coping methods of life (such as the gym, watching a movie at the theater, visiting with family or friends, etc.), some of the popular coping mechanisms that emerged involved creative expression. While some people began recording themselves in different manners, finding new hobbies, or just making varying attempts to reconnect with others, the commonality between all options was the use of a mobile device. All in all, during the pandemic, mobile devices were quickly singled out as the primary, and addictive, lifeline for society—one that kept us all connected to our very detriment.

Another source of creative expression, and escape from reality, was the surge of digital comic books. According to ICv2’s Milton Griepp and Comichron’s John Jackson, total comics, and graphic novel sales to consumers in the U.S. and Canada were approximately $1.28 billion in 2020, a 6% increase over sales in 2019 (Miller 2021). Digital sales of major and independent comics would also later increase overall sales to 62% by 2021 (Milliot 2022).

Independent comic anthologies and memoirs became popular alongside the rise of ‘graphic medicine’, or comics that focus on an illness (Czerwiec et al. 2015), to advocate and educate during the pandemic, while others focused on the horror-like experience of existing during the pandemic. The following analysis will examine doomscrolling in two works created during this time. Covid Chronicles, and Quarantine Comix similarly use short comics to express their views on the pandemic, roles mobile technology played during the pandemic, and more precisely how mobile technology served as a catalyst to the monstrosities of ‘normalcy’ in the quarantine era.

In the first work analyzed, the anthology Covid Chronicles, creator Kendra Boileau teamed up with Rich Johnson, a judge for Eisner Awards, to create a collection of over 60 comics that spoke to how individuals, societies, governments, and markets reacted to the worldwide Covid crisis. While Boileau did not have much experience at the time with comics that focused more on artistic expression, she is known for her development of the Graphic Medicine line of graphic novels for PSU Press. Given her experience with comics that educate readers on illnesses and treatments, this anthology was chosen as an example of how graphic medicine creation shifted during the pandemic to illustrate new external and psychological horrors.

In contrast, the second work, Quarantine Comix: A Memoir of Life in Lockdown, shifts to the singular perspective of creator Rachael Smith. Rachael Smith created a comic for every day of lockdown (200 in total) and created a memoir of her individual experience during the pandemic. Though Smith’s comics historically focus on her battles with mental health, Quarantine Comix offers a similar focus but speaks to the overall shared experience of the pandemic and the battle with loneliness, isolation, and other monstrous melancholy experiences.

Comics are ‘juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer’ (McCloud 1993). They can be used to challenge systems of power, raise social concerns (McAllister et al. 2001), and ultimately raise a mirror to the society they represent. In other words, comics can be studied as cultural artifacts to inspect a society and uncover some of its many cultural challenges. Generally, comics tend to focus or respond to cultural crisis (such as the pandemic) to reflect and document the ways in which society deals with such events (Saji, Venkatesan, and Callender 2021). A common depiction in pandemic comics is the specific way in which an author builds tension within the frames to demonstrate the use of mobile technologies, and how they represent a frequent and shared experience within society during the pandemic—doomscrolling.

Analyzing Doomscrolling and the Covid Pandemic

While examining the ways the Covid pandemic introduced monstrous routines of what became ‘a new normal’, comic authors and creators depicted their horrors during the lockdown period. To successfully reach their readers, or rather, unite under a shared experience, authors had to build precise tensions that allowed readers to ‘act as the authors active accomplice’ (McCloud 1993) in developing understanding and meaning. In other words, authors had to successfully portray the many layered tensions of doomscrolling in a manner that readers could easily relate to.

Doomscrolling is a term used as early as 2018, however its use drastically surged during the lockdown phase of the pandemic (Jennings 2020). Many individuals felt tethered to their mobile devices, more so than ever before, as it served as a main lifeline to the outside world. While individuals utilized platforms for video calling and socializing more than before, people also used it to consume news and updates around the quickly spreading virus. During this period, the Covid pandemic was not the only existing horror. Humanity continued to face an escalated confrontation with police brutality, misinformation, political anxieties, as well as mundane horrors introduced by isolation, boredom, and a hyper focus on anxiety-inducing news cycles. People were drawn to their devices because it was a lifeline to their friends and family and allowed them to still be connected but was also a significant contributing cause of their internal anxieties and fears.

While it’s likely many people participated in ‘doomscrolling’ prior to the pandemic, it was almost unavoidable during 2020. Quartz reporter, Karen Ho, popularized the term with tweets asking, ‘are you Doomscrolling right now?’. In an interview with Vox, Ho touched on why so many people were consumed by the act. She states, ‘It feels productive and like we’re exercising our agency during a period where we can’t do much and so much choice and variety has been taken away, even though it’s often neither of those things’ (Jennings 2020). This constant cycle of mundane horror is commonly expressed in the pandemic comic anthologies and offers a stark difference in how the horrors of mobile technology were expressed in this medium previously.

While looking to some comics produced during the pandemic, it is important to understand the significance in how certain elements of this period are depicted and how mobile devices are used to depict internal expressions of anxiety, dread, or chaos. In examining mobile use in the following comics, text and visual imagery will be analyzed for societal anxieties, fears, ideals, and desires around the pandemic (Langsdale and Coody 2020: 3). More importantly, the comics will be analyzed for their creator’s commentary around doomscrolling and imposed psychological horrors incited by Covid and the adjustments to surviving the pandemic. In examining these aspects of the comics, I will be using Charles Hatfield’s tensions (2009) as a lens to better understand the variety of interpretations left by the author and the active role the reader plays in forming meaning through these potential interpretations. This lens is useful as Hatfield’s Alternative Comics serves as an overall discussion on comics and provides preconditions and key examples of how comics are understood as a literary form. Hatfield defines four types of tensions found in comic art: code vs. code (word vs image), single image vs. image in series, narrative sequence vs. page surface, and reading as experience vs. text as an object (2009).

Doomscrolling in Comics

Covid Chronicles: A Comics Anthology was released in 2021 (Boileau and Johnson 2021), and contains the works of over 50 creatives, all of which submitted short comic panels on different perspectives and experiences during the early stages of the pandemic in 2020. The first of many doomscrolling representations is illustrated in the short, Shelter In Place Sing (Marrs 2021: 119–23). This comic stands out as a prime example of multiple difficult and stressful experiences in a short period of time. Readers are told a short story about a young girl who is isolated from her primary care givers (her parents) while forced to withstand the constant shortcomings of the government. Her immediate and temporary caregivers (her grandparents) are terribly impacted, which leaves our main character wrestling with inescapable doom all around her (family, television, social media). This example stands out as an overwhelmingly shared mundane horror of the pandemic crisis. It is the delicate balancing of everyday, inane tasks, dread, and shortcomings of the world’s governments in protecting the people from widespread disease that create these relatable situations.

The reader starts out with a god-view of the earth covered in virus clusters (meant to depict the rapid and global spread of Covid). We see our protagonist, Jaz, sitting in a room with her grandparents. She observes with a look of panic as they argue about their fears and lack of awareness by then-President, Donald Trump. Readers are made aware the conversation between Jaz’s grandparents teeters into an argument and is a high-stress conversation because of the tension presented between the text and the images. Hatfield points out that ‘words can be visually inflected’ (2009: 54) meaning the use or emphasis of certain words can be as clear as looking at an image. Though the conversation between the grandparents is written in text bubbles, a form commonly used in comics, we know tone and word choice is being emphasized by the selective use of bolding. With ‘royally pissed’ being the first bolded part of the conversation, the reader receives the tone right away and knows the character has an aggravated tone followed by ‘CDC?!!!’ and ‘grumble, grumble’. Without providing any more context, the grumble implies grandpa is still carrying on the conversation with a similar tone but there is no need to home in on the details.

The emphasis placed on WHO and CDC in the same manner as ‘royally pissed’ implies the same tone is being used to discuss political/governmental components. Readers can easily interpret the political ideology of the grandparents simply with the grandmother’s response of ‘We just didn’t hear about it. Remember who’s president?’ The tension in this panel is delivered to the reader by using bold font as a tool to denote the tone in the room. This aligns with the stressful expression drawn on Jaz’s face.

In the next panel, we watch as Jaz video-chats with her parents and their background of tropical trees, alluding to them being separated as impacted travelers who were left stranded in a different country because of different travel restrictions. Here, the author has created a subtle reference to a specific topic within the pandemic crisis and leaves the reader to create meaning and understanding through this shared experience.

As Jaz sits down to watch TV with her grandparents, they are immediately hit with the darkly lit news of hospitals overwhelmed with patients and rising death tolls. Although there are no speech bubbles, we know the TV is on and most likely displaying narration from a news channel. The author makes the decision to include a real image of a hospital scene rather than an illustrated image which is uniformly used in all other panels. This change in image style affords the reader the ability to identify similar news clips they have already seen in real life, which again, also allows them to draw from the experience and create the understanding of what is happening in frame.

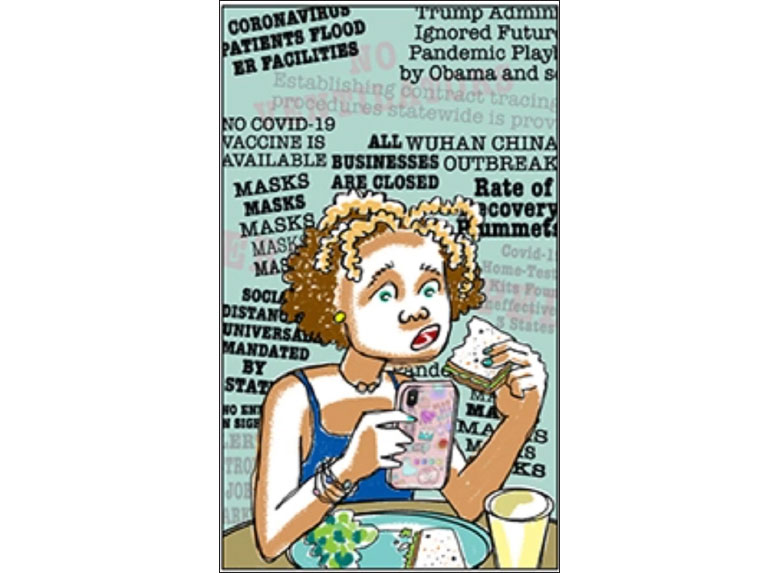

Readers are then presented with Jaz sitting at a table to eat and scroll on her phone (Figure 1). Jaz sits with a look of discomfort and concern as her background is plagued with texts that allude to different headlines or topics, she helplessly sifts through in her act of doomscrolling. The headlines overlap each other in gray, black, and bolded text to depict the chaotic emotions experienced simultaneously within the single timeframe of the last panel. The different headlines, in no special order, read as ‘Coronavirus patients flood ER facilities’, ‘no ventilation’, ‘masks, masks, masks, masks’, ‘all businesses are closed’, ‘no covid-19 vaccine available’, ‘rate of recovery’, ‘Wuhan China outbreak’, ‘social distancing mandated by state’, ‘home tests’, ‘contact tracing’, ‘Trump administration ignored’, and a couple of others that are not as clearly shown.

The overlapping headlines contribute to the illustrated shared experience Marrs is building for readers—while most of us were locked inside and cut off from our normal routines, we were forced to consume the constant flood of news spewing from multiple sources to both stay updated and connected. Whether the topic was fake news, political news, social revolutions, illness, death, or fear, many individuals were suffocated by the never-ending tap of doom. The narrative Marrs creates in her short speaks to this feed and the mental repercussions it had on people. Marrs also creatively depicted the distrust of governmental regulation many had regarding Covid.

This panel’s pictures are a clear example of the tension between text and image. With each overlapping headline written in the background, the tension continues to build as certain headlines are bolded, are written larger than surrounding text, are in a different color, or are so jumbled it is hard to even read clearly. Similarly to how Hatfield discusses sound effects in comics, these headlines ‘are not part of the fictional world’ we are physically presented in the panel but of the chaos presented by the mobile device in Jaz’s hand. Although there is no obvious sound in the panel, the reader is offered a format that enables them to ‘hear’ the sounds of the repeated doom-focused news headlines being distributed on news sources. Though Jaz escapes the mundane horror of watching the doom presented on the news, she rather decides scrolling through it is her only alternative—replacing one form of doomscrolling with another.

The shift from one form of doomscrolling to the overwhelming beratement of headlines illustrates the mundane horrors associated with the growing reliance of mobile technology during lockdown and the negative effects that are associated with it. This tells readers although Jaz can communicate with her parents, there is still an overwhelming uncertainty around their safety, her safety, and the overall situation at hand. The artist makes it obvious Jaz is doomscrolling because we can see the various click bait headlines taking over her entire background overlapping each other while Jaz looks at her phone with furrowed eyebrows as she sits at a table eating food. Her environment suggests safety as she is sheltered with her grandparents and being fed, however she welcomes the mundane horrors of pandemic related news and overly biased opinion pieces by scrolling through a constant feed of anxiety and fear-inducing information.

The depiction of tension in these panels, compared to previous works from the artist, demonstrate a stark difference in how ‘chaos’ and ‘tension’ are illustrated. Looking back to some of the artists previous works, we can see a recurring theme with narratives around society, but the distribution of them changes with time. For instance, in the comic series Pudge, Girl Blimp, Marrs tells the story of a teenage runaway during a time of street protests, self-help clinics, burglary, job hunting and midnight pizzas in the 1970’s (Marrs 2016). With just about as much social disruption as the pandemic, Marrs illustrates a time where mobile technology was not yet prevalent, and ‘doomscrolling’ may not have yet existed in the current context but could be demonstrated through similar tensions of text and imagery in printed media. In a very popular cover of this work, Marrs illustrates a multitude of overlapping images that speak to different aspects of the social and sexual revolution during that period.

Looking back to Shelter In Place, Marrs creates tension with the reader using overlapping visual text (creating a sense of an overload of information) whereas in her cover illustration of Pudge the girl blimp, Marrs creates similar tension using overlapping images of different social groups and events. This then speaks to an in-person tension, or rather a tension the reader is familiar with through their personal experiences of ‘urban life’, whereas the tension of Shelter In Place, speaks to a tension one experiences in isolation—the difference here being one of tension through connectivity and the other through separation.

In the short April 11–15, created by Rob Kirby (2021: 162) we are introduced to our protagonist waking up at 4:00 am and going about his new and mundane routine during lockdown. He lays in bed for about thirty minutes then begins to doomscroll on his laptop—making a point to state all the headlines were bad. Kirby begins building tension in these panels using ‘pictographic language’ (Hatfield 2009: 56). Kirby surrounds himself with vector lines, like lightning bolts, which creates the atmosphere of stress or doom (like what we faced in lockdown). By 7:30 am, our protagonist has a conversation with his partner, John. They discuss the need for space which is followed by a nerve-wracking trip to the grocery store. They are surrounded with sweat, dark shading, and zig zag lines to depict their heightened and unwelcomed stress and anxiety around the experience (McCloud 1993: 125). Again, the author is building tension in the scene but now homing in on the new levels of stress and fear when attempting to carry out simple, regular tasks in stores where we are routinely mingled with strangers. The following panel contributes to the sense of chaos by shifting the focus to Kirby’s internal dialogue.

As our protagonist continues through his days, the panel for Sunday 4/12/20 stands out. Our protagonist is drawn for the first time in a solid black color (Figure 2) with dark black clouds and lightning striking just above his head. There are no internal or external dialogues taking place in this scene, however readers are shown a large headline—’The US now has the most reported Coronavirus deaths of any country’. In the frame, it is clear the artist is making a very direct statement on the emotional state of our protagonist (McCloud 1993: 192). The tension in this panel is provided via vector lines similarly styled to the previous vector lines.

In this scene, the vector lines, harsh shading, and lightning are all techniques used by Kirby to create a shared understanding with the readers. Storm clouds can easily be understood as a representation of doom/dread, and Kirby is counting on this to resonate with readers. He takes his own experience and reproduces it in a way that echoes with anyone. In fact, the lightning being produced from the cloud is directly aligned with the mobile phone pointing to the source of the entire panel’s negativity. The harsh shading and vector lines also share the same effect in showing readers this particular action immediately takes our protagonist into a dark mental state.

The only other time we see our protagonist drawn in solid black is on Wednesday 4/15/20 when he is overcome with complete dread of being locked inside and the constant ticking of a clock pushing him closer towards feelings of insanity. Readers are aware of the significance of the shading because of the timing of its use and the context within the frame. The shading of Kirby is done consistently until the bottom portion of his torso, which then becomes harsh scribbling—a similar style shown to strong negative emotions or thoughts. Again, there is no use of dialogue or words, but the text used is to create sounds for the reader of a constant, loud, and maddening ‘TICK’.

The readers can easily align with the mental stage Kirby is setting once again. The repetitive use of ‘tick’ combined with the apathetic look from the protagonist creates an unpleasant understanding. What really allows the readers to understand Kirby’s mental state here is the use of sound effects trailing into the protagonist ears, along with the not completed dark shading implying that with every ‘tick’ he is filled with slightly more dread.

In this comic, the author uses many code vs. code and narrative sequence (Hatfield 2009: 53) techniques to tell a story of internal psychological horrors while also facing the horrors of mundane routines. First, we know there is a monotonous routine because we are made to watch our protagonist go through his lockdown routine step-by-step through the narrative sequence that Kirby has built out for us—the order in which you review the panels (with exception of the end) do not take away from the monotonous routine he is sharing with readers. Readers are taken through the mundane progressions of Kirby’s day but are shown multiple forms of tension in the use of text, images, and sequence of events. Secondly, readers are made aware of the monstrous routine because of the tension built between text and image (code vs. code). Kirby shows tension in how his words are drawn as sound effects, and the impact the repetitive use of those words has on our protagonist (dark shading and harsh vector lines.)

We are also given the backstory that our protagonist and his boyfriend might, at the very least, be irritated with each other’s constant presence and inability to get the necessary space away from one another. We know there are feelings of dread because of heavy line use and the illusion of repetitive sound—like the ticking clock. We are also told very directly our protagonist is doomscrolling because of the use of dark shading and an overhead storm all while holding a mobile phone. The artist does not bring attention to any specific headlines or topics, but we know right away whatever is being shown on screen elicits immediate feelings of dread and anxiety.

The dichotomy between mixed feelings during lockdown of the pandemic is shown in the final panel of the story as the protagonist sits down to watch Ru Paul’s Drag Race and find peace (or just escape from reality) in the more tolerable portions of his new mundane routine. The entire short provide readers with the back and forth of forcing oneself through their mundane routines of survival during Covid—waking up, being locked in the house, handling basic errands while avoiding most to all human interaction, and finding a sense of normalcy or peace in distracting oneself from the current state of panic.

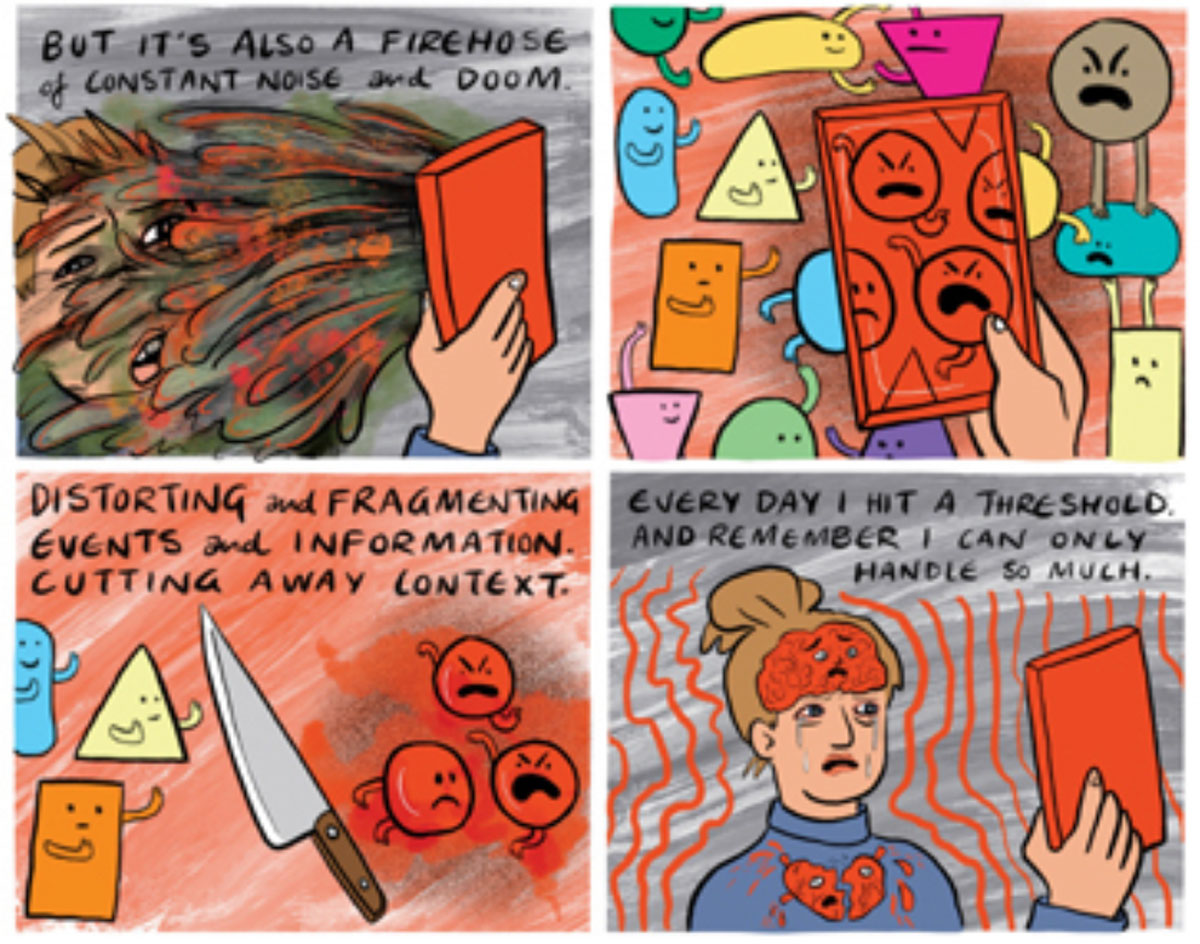

State of Emergency by Sarah Firth kicks off with the protagonist narrating her experience at the start of Covid and how it ‘hit Australia on the back of the devasting bushfires’ and how one mask was swapped for another (2021: 177). The comic short utilizes the contrast of bright orange and reds as well as black, to provide a detailed view of the burning chaos occurring in Australia, followed by its gloomy outcomes. Firth also uses a mix of both European ‘clear line’ (Hatfield 2009: 76) styles and ‘ratty line’ approach (Hatfield 2009: 78) styles to portray her story. Clear lines are shown in how the characters are drawn to portray them carrying out their routine tasks, while ratty lines are used to portray the internal and external expressions of chaos or doom, or rather their internal or emotional conflicts.

There is no dialogue in the scenes, however Firth provides narration above the images throughout the short. The format of the text has no boundaries, or bubbles, and instead they are added to the frame as a secondary code next to the images. Tension is shown through the text using font size and/or bolder lines. This creates the illusion that Firth wrote this down herself, digging her hand down harder to emphasize the sentiments or emotions of each scene. Firth describes her mobile phone as ‘lifeline’ in one panel and then a ‘firehouse of constant noise and doom’ in another (Figure 3). Readers watch as the protagonist holds her phone up to her face as monstrous-like figures with dark shading begin to sprawl out onto her. Again, we see the use of the symbiotic tension that exists with the technology as in Boileau and Johnson referenced above.

In this strip, Firth does well to focus on the dichotomy between feelings of connectedness and feeling of helplessness. This representation is a key element for understanding how Covid comics speak to a shift in depicting everyday life and how mobile phones in these comics are used as a demonstration of both positive and negative impacts on individuals during this time. In some of Firth’s previous works, before the pandemic, she speaks a lot to connectedness using proximity to other characters or outside, rather than being tethered to a mobile device.

She also alludes to the monstrosity of misinformation during the pandemic—a very common issue involving social media, news outlets, and other outlets for pandemic related news, which she continues this conversation in her later works such as Bullshit Buffet. In the last frame, we see the immediate impact doomscrolling has on the main character as we watch her cry. Red wavy lines outline her body emphasizing her internal state, which is clearly drawn as an anxious or worried mind and a broken heart. Here, Firth builds tension for readers using specific colors and vector lines as well to create the modality of the scene. The red coloring is commonly understood to be symbolic of a form of danger, while the vector lines are ‘diagrammatic symbols used to exploit the tension’ (Hatfield 2009: 56) of the situation readers are joining.

While Firth does not focus on the opposing effects of mobile usage during the pandemic, her focus is mostly placed on the spread of misinformation. Readers are provided with a single panel of different shapes meant to represent people and/or events. Firth places her camera, as an added layer, over the shapes’ perspective changing the shapes from colorful, somewhat happy, or neutral images to red blobs with angry/doom-stricken faces. Admittedly this can just be one interpretation of the use of shapes. This form of ‘visual dialogue’ (2009:57) demonstrates how there is no need to rely on verbal tensions when symbols are played against each other. These depictions of spread misinformation are also used to parallel the spread of wildfires—shifting from one monstrous norm to the other.

State of Emergency reflects on the already chaotic time of the Australia wildfires and in combination with Covid, the author creates a sense of normalcy in the constant redundancy on chaotic times. Readers are presented with a character and her narration of the lived experience of piggybacking one disaster to another.

Shifting over to the works of Rachael Smith, she also focuses on the dichotomy between mobile technology being a savior while also being a catalyst for internal dread. In Quarantine Comix (2021), Smith humorously reflects on her time during the height of the pandemic and the toll it played on her mental health. In Figure 4, we watch as her cell phone is used as a constant vehicle for information that has a negative impact on Smith’s emotional state (2021:27). She separates her feelings of doom into categories of fear and loneliness. Smith creates tension here by separating two emotions into a split panel rather than separate individual panels. Due to this layout, readers are made aware of the negative impacts that are attached to the pieces of text and the strain that exists between the two.

Here Smith uses text to focus on the mixture of anxieties—uncertainty, death, and helplessness. Readers can see the author is clearly upset and avoidant of her mobile device by standing away from and looking down to it with tears. While the text from Smith is read as a narration we can see multiple speech bubbles, sourced from her mobile device which can be interpreted as doomscrolling headlines, or bits of information she is receiving from social media—either way, readers are aware of the constant stream of ‘doom’ because of the use of more than one speech bubble. Since we know Smith is locked down during the pandemic, we know her only attachment to others is her mobile device, so she is ultimately tethered to the doom of the pandemic, making it a monstrous routine.

Smith speaks to the negativity sourced from her mobile device first, before ever acknowledging positive impacts. In the frame of loneliness, the text highlights social media posts from people in relationships with the ability to share this experience with someone rather than bear it alone. We are made aware of this because of the tension of the narration with the dialogue bubbles coming from Smith’s mobile device. Notabley, the expression from the above panel is a stark difference from the panel below showing readers that in either scenario Smith is experiencing negative emotions. In the last frame of this short, Smith goes from an expression of dread and discomfort to complete happiness and satisfaction. This quick and blatant difference comes almost as a catch line to a joke, but also serves as commentary on the mixed sentiments towards mobile devices. In one regard, mobile technology tethers us to a constant stream of bad news and dread—doomscrolling—and in another regard it can be our only lifeline to others and social connections.

This was a common sentiment throughout the pandemic, making these anthology comics quite relatable to readers while also suggesting the more widespread cultural impacts the pandemic had on real life routines and how real life is depicted in comics. This recurring theme is easily identified in multiple Covid comics produced during the pandemic and are reflected in the comics highlighted in this article as well.

In Smith’s lockdown routine, she makes clear she is torn between the two sides of her phone—needing it to feel connected but also being addicted to the internal doom is disperses. Readers are made aware of this routine because rather than walk away from her feelings of dread, Smith draws herself glued to the table just watching as her device delivers anxiety inducing information. The use of multiple text bubbles jumping out of her phone produces the same overwhelming response as if multiple text messages had all been delivered at the same time or everyone speaking at once—this constant stream confirms Smith is in fact doomscrolling and shares the negative impacts it has on not only her mind but the overwhelming hopelessness she and most people experienced during the pandemic. The beratement of text serves as a ‘radical synchronism’ (McCloud 1993: 95) and can also be understood as the passage of time within the frame, as it is unlikely the character can simultaneously read more than one gloomy news headline. Time not only exists within Smith’s complete comic anthology, but also within the panels themselves (Hatfield 2009: 70).

Smith calls attention to the monstrosity of mobile devices during the pandemic once more by creating tension within a full-page panel (Figure 5). She sits on the floor, wrapped in a blanket as she clutches to her phone (2021:190). There are imaginary characters on either side of her, the dark representing her negative state of mind, and the light to represent the positive. Depicting both her negative and positive internal states in a constant tug of war as she stares down at her phone. On this page, readers are told right away that this image is very important, so important it had to take up a whole page. Since the complete anthologies within this book are different monotonous routines Smith experienced during the pandemic, readers are made aware the use of a single image is representative of a reoccurring and thematic like event. The page is also used to create tension between images and Smith’s internal state.

Smith is focusing on the dueling impacts of mobile phones during the pandemic—one side being negative (doomscrolling) and the other positive (socialization). We know this because each side is literally tugging on either side of Smith as she sits stressfully looking at her phone. We are also made aware of the tension because of the use of black and white like how a ying-yang symbol would be depicted. Smith also tells readers this is her current and most prominent struggle during the pandemic, at least during the lockdown period, which has been established as a very common and universally felt theme during this period. While her struggle with mental health may have existed prior to the pandemic, the forced emphasis on mobile technology has tethered her to a more fragile horror she cannot escape, thus creating a monstrous routine during the pandemic.

Conclusion

Although the term ‘doomscrolling’ had been used pre-pandemic it was not considered part of a regular day routine until Covid and the lockdown period of the pandemic. Prior to 2020, most previous depictions of mobile usage did not focus as heavily, or at all, on the mundane horrors of being tethered to a device that brings both joy and discomfort routinely. However, comics that did manage to address cell phones before Covid focused on how they contributed to disconnections from external relationships (i.e ignoring your partner at dinner to look at your phone rather than engage in conversation.) The shift from external negative impact to internal negative impact (anxiety and fear) in comics distinctly came during the lockdown period of the pandemic while everyone was forced to disengage with others and stay inside.

To understand doomscrolling as a component of monstrosity, the surrounding context of time, political climate, and current events need to be analyzed in conjunction. This requirement of readers mandates an active role in working with the author to create meaning. Doomscrolling is a phenomenon that a mass majority have all experienced and unanimously understood its meaning and impact. Due to this fact, the expression of doomscrolling in story telling can be done in a variety of ways but can still be understood broadly. Ultimately, doomscrolling can be viewed as a shared experience that depicts a mundane but monstrous repetitive routine.

Comics created during the pandemic focused on the experiences of isolation and panic, which resulted in much auto-biographic story telling. Interestingly, these comics introduced a new component to depicting everyday life that has never been highlighted to this degree in the past. A recurring theme and focus of these creations involve the freedom and monstrosity that both come from mobile technology. The pandemic and lockdown allowed (and forced) many people to reflect on their habits and home in on their sources of discomfort—thus not only evolving our shared experience within society but the routines in which we willingly or forcibly partake in.

The tensions of these comics are depicted through text, images, and sequential layouts of the stories themselves leaving readers to construct their own meaning/understanding based on their own shared and expected experiences during the pandemic. While the expected monstrosity in these tellings is the virus/pandemic itself, the secondary monstrosity is the mundane routines formed while living though the monstrosity of the Covid pandemic. Covid introduced new waves of what will now be considered normal routines, and thus, also impacted on the ways in which normal interactions with mobile technology are discussed and depicted in comics today.

Editorial Note

This article is part of the Conjuring a New Normal: Monstrous Routines and Mundane Horrors in Pandemic Lives and Dreamscapes Special Collection, edited by Alexandra Alberda and Julia Round, with assistance from the editorial team.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Boileau, K and Johnson, R 2021 Covid Chronicles: A Comics Anthology. Penn State Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9780271091723

Firth, S 2021 State of Emergency. Covid Chronicles: A Comics Anthology, 177–183. Penn State Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9780271091723-043

Hatfield, Charles 2009 Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. Univ. Press of Mississippi.

Jennings, R 2020 Doomscrolling, Explained. Vox. Available at: https://www.vox.com/the-goods/21547961/doomscrolling-meaning-definition-what-is-meme. Last accessed 20 August 2022.

Kirby, R 2021 April 11–15. Covid Chronicles: A Comics Anthology, 161–65. Penn State Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9780271091723-039

Langsdale, S and Coody, E R 2020. Monstrous Women in Comics. University of Mississippi Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.14325/mississippi/9781496827623.001.0001

Marrs, L 2016 The further fattening Adventures of Pudge, Girl Blimp. Marrs-Books.

Marrs, L 2021 Shelter-In-Place Sing. Covid Chronicles: A Comics Anthology, 119–23. Penn State Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9780271091723-028

McCloud, S 1993 Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Miller, J. 2021 Comics and Graphic Novel Sales Hit New High in Pandemic Year. Available at: https://comichron.com/blog/2021/06/29/comics-and-graphic-novel-sales-hit-new-high-in-pandemic-year/. Last accessed 25 September 2023.

Milliot, J 2022 Comics/Graphic Novel Sales Jumped 62% in 2021. Available at: https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/financial-reporting/article/89752-comics-graphic-novel-sales-jumped-62-in-2021.html. Last accessed 25 September 2023.

Price, M., et al. 2022 Doomscrolling during COVID-19: The Negative Association between Daily Social and Traditional Media Consumption and Mental Health Symptoms during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001202

Saji, S Venkatesan, S and Callender, B 2021 Comics in the Time of a Pan(Dem)Ic: COVID-19 Graphic Medicine, and Metaphors. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 64(1): 136–54. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2021.0010

Smith, R 2021 Quarantine Comix: A Memoir of Life in Lockdown. Icon Books.

Ytre-Arne, B and Moe, H 2021 Doomscrolling, Monitoring and Avoiding: News Use in COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown. Journalism Studies, 22(13): 1739–55. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1952475