Background

When we first put the call out for this special collection, it was amidst governmental demands that their citizens adjust to ‘new normals’ and at a time when publics seemed split: between those who wanted to get back to everyday life and those who thought that we weren’t ready to retire our masks or return to shared spaces. Many of these concerns are still relevant some years on. We were interested in the comics that emerged as a result of these differing perspectives, and especially in how comics artists employed different genres, tropes, and symbolism to convey this, particularly relating to the Gothic.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals came forward with their talents and interests to try and help other people, from bakers to health trainers to gardeners and beyond. Among those, and not only noticed by those of us already watching and following them on social media, were comics artists, who started to create and share pandemic comics - mostly online, but followed by print formats. Comics anthologies produced during the pandemic presented a wide range of experiences, while also focusing on specific places or people. These works include: COVID Chronicles: A Comics Anthology (2021) edited by Kendra Boileau and Rich Johnson, COVID Chronicles (2020) by Ethan Sacks, Dalibor Talajić, and Lee Loughridge telling stories from the frontlines, PANDEMIX: Quarantine Comics in the Age of ‘Rona (2020) edited by Dean Haspiel and Whitney Matheson to support artists from the Hero Initiative: Helping Comic Creators in Need, “Pandemic” News Project (2020) by the Charlotte Journalism Collaborative to tell multiple perspectives from Charlotte NC, and The Lockdown Lowdown: Graphic Narratives for Viral Times (2022) zine series, including a special issue on “Women and Covid, a gendered pandemic”.

These comics ranged from informational comics that educated about different aspects of the pandemic, to stories of people’s isolated and ‘new’ normal lives, to social change-focused comics that showed how the pandemic exacerbated inequalities such as racism and poverty. Doctors, nurses and other medical professionals used the medium to tell about their experiences in the field and to take readers behind the hazard doors that blocked many people from seeing loved ones and the reality of hospitals. At the start of the pandemic the Graphic Medicine Collective started organising the comics they came across into genres to demonstrate the breadth of the work created. This introduction doesn’t have the space to detail all the different ways comics creators engaged with readers, communities, and different initiatives around the world, nor the space to analyse how they were technically shared via social media. But amidst their various formats, genres, and stories, these creators also conveyed a range of emotions and tones in their work and the wider spaces of social media platforms afforded readers a glimpse into their intentions, such as calls to actions, sharing information on how to get help, and how the creators were personally doing during these times.

Beyond the production of comics, the authors of this special collection add their work to the growing body of scholarship that has reflected on pandemic comics. While comics have featured in wider discussions of the pandemic, such as Pandemics and Epidemics in Cultural Representation (ed. Venkatesan et al 2022), the vast majority of research takes the form of journal articles. These come from both science and humanities backgrounds, and take in many different disciplines and scholarly fields (social science, medical humanities, and artistic or literary criticism). They may be practice-based (such as Whatley 2022) or critical in nature. Some consider the means by which comics have represented the pandemic itself, considering elements such as metaphor (Saji et al 2021) or humour (Jürgens et al 2021). However, the majority take a more applied approach, for example exploring the ways that comics can be used beneficially to manage the effects of the pandemic. Kearns and Kearns (2020) investigate the potential of comics to aid public health communication by conveying scientific information in engaging ways, while scholars such as Malau et al (2021), Saputra and Pasha (2021) and Utomo and Ahsanah (2020) - and many more - explore the potential of digital comics as learning resources to enhance homeschooling in subjects ranging from biology to grammar.

Many critical studies explicitly contextualise the pandemic against intersecting social issues, such as the Black Lives Matter protests. For example, Krishnan et al (2020) draw attention to the ways that pandemics past and present have disproportionately affected Black populations in greater numbers. West et al (2023) detail the methods and impact of their pilot study on the ways that graphic medicine workshops can enable wellbeing and resilience in the intersecting contexts of the pandemic and racial injustices. Venkatesan and Joshi (2023) explore the power of comics as counter-narratives to the increased levels of discrimination faced by East Asians in the wake of the pandemic. This very brief snapshot suggests, perhaps, that in some respects the pandemic has moved comics analysis away from literary close readings of exceptionalist texts, towards a greater emphasis on applied studies and a wider consideration of social and contextual factors.

When we devised this call for papers, we framed it in Gothic and monstrous terms, focusing on the way that the pandemic revealed buried risks, changed mundane routines, created haunting worries and traumas, and made ‘spectres’ such as debt, loss, anxiety and uncertainty newly visible. We were interested in exploring the fears of the cultural moment and how these had informed the themes and moods of the comics stories being told. Gothic has long been theorised as a response to social trauma (Punter 1980: 14) and as a means to articulate cultural fears. A focus on monstrosity and contagion underpins some of the best-known Gothic archetypes (the vampire, the zombie), which exist at the borders of life and death - a space that perhaps feels all too appropriate to pandemic living. The ways in which borders break down, as social norms are discarded, rules are transgressed, and invisible fears become visible threats, is something that this collection explores effectively. This is something that comics seem well-suited to do, as both comics and Gothic carry similar tensions within them. Radcliffe ([1826] 2023) suggests that Gothic oscillates between the expansion of terror and the contraction of horror, and later scholars have explored the ways that many of its underpinning critical concepts (the abject, the uncanny) revolve around the collapse of boundaries or meaning.

Comics are also full of tensions and dichotomies: as a multimodal form which also relies heavily upon reader involvement. Their storytelling is simultaneously paradigmatic (the spatial page layout) and syntagmatic (the linear story created); giving readers a fragmented tale that nonetheless carries holistic meaning. Considering pandemic comics thus offers a way to explore comics’ formal storytelling, by examining the ways that creators use the medium to create affect and frame emotion. Comics have been argued to be a gothic medium in many ways (Round 2014: 2019; Schneider 2014; Smith 2007), within links between the two fields being identified across multiple aspects, for example as Round (2019: 419) also argues that ‘comics can be considered Gothic in historical, thematic, cultural, structural and formalist terms’. In broad strokes, the historical argument draws on a shared history of (Western) woodcuts and (Eastern) genres such as ukiyo-e that depicted gory or fantastical scenes, and the impact of the global response to ‘American-style’ horror comics of the 1950s. The thematic argument notes the presence of transformation and mutation in popular genres ranging from the early nineteenth century to the contemporary superheroic (Ahmed 2019) and the way that other Gothic themes such as trauma and isolation inform contemporary genres such as autobiographix (Schneider 2010) and graphic medicine (Green 2023). A tension between high and low culture informs both Gothic and the comics medium (Pizzino 2016) and many fan practices enact a similar set of tensions (Round 2014). The accessibility of small press comics, webcomics, zines and other self-publishing formats sits in counterpoint to top-down industry practices and publishers’ rigorous protection of their intellectual property and copyright. These tensions also underpin comics structure and narratology, for example as storyworld borders are transgressed or word and image are juxtaposed, placing readers in uncanny positions that disturb and fragment identity.

Themes and content

The appropriateness of comics to express moments of fear and tension and their accessibility as a form of creative expression both speak to the pandemic moment. This foregrounded unspoken fears and tensions, as sickness statistics and political feelings became the subject of everyday conversation. Simultaneously, many found themselves looking to fill time at home by seeking new creative outlets (from baking sourdough to mask-making) and moments of community interaction (online quizzes, social media and zoom calls). Both new states demonstrate a democratisation: towards (newly spoken) themes and (newly creative) activities that comics were well-placed to fill due to their affinity to stories of the self and ease of production and distribution.

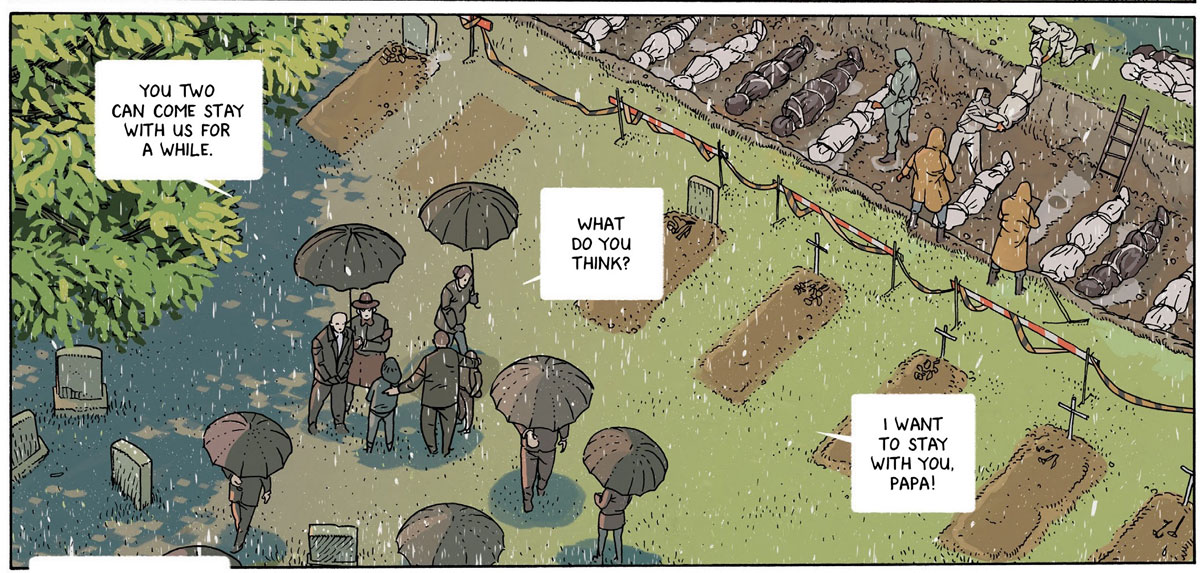

The articles in this collection engage with these ideas and provide unique angles on comics creation and communities related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the difficulties experienced during the establishment of ‘new normal(s)’. In our first piece, ‘Necropolitics and Pandemic Premediation in The Fall’s Neo-Western State of Exception’, Anna Marta Marini and Michael Fuchs explore the ways that this series anticipates many of the social issues of the pandemic, including the collapse of boundaries and borders (between city and nature; between panels), the juxtaposition of government rhetoric with lack of action, and the (re)creation of systems of hostility, sovereignty and social hierarchies as people were forced into new spaces (Figure 1). Marini and Fuchs investigate the impact of the comics medium in creating and foregrounding these themes through juxtaposition, the (ab)use of refugee visual tropes that sustain mass representation and anonymity over individualism, and character focalisation (Marini and Fuchs 2023).

Marie’s death is visually put into the context of the flu pandemic’s death toll, The Fall collected edition, 2021: 20 © 2021 Jared Muralt. In Marini and Fuchs 2023.

Donald Unger’s exploration of ‘Collectors, Storytellers, and Web Pros: Making Comics and Building Community During the Pandemic’ then takes a different perspective by exploring the development of three online comics communities during the pandemic. Unger’s position as a participant-observer in these communities and both comics creator and comics scholar gives him a unique perspective from which to offer ethnographic observations on the way that the pandemic affected existing comics communities and events, before closely looking at three case studies. These discuss the different dynamics and platforms used by the ‘Cartoonist Kayfabe’ YouTube channel, the ‘Sequential Artists Workshop’ online workshop programme, and the ‘Comic Lab’ activities including their podcast, Patreon and Discord discussions. Unger’s ethnographic discussion explores the ways that categories of collecting, storytelling, and professional practice interact in these communities and emphasise the myriad of priorities available to comics creators, scholars and fans both on and offline (Unger 2023).

Stephanie M. Garcia also analyses the online world of the COVID-19 pandemic, but this time by examining how comics artists depicted doomscrolling and the impact of mobile technology in the time when the concept of ‘new normal’ was becoming a part of the later pandemic. She argues that mobile devices became lifelines and objects of anxiety due to social isolation during the pandemic and the constant stream of negative news people encountered through increased online lives. In ‘Expressions of Doomscrolling in Pandemic Comics: How Portrayals of Mobile Technology Shifted to a New Normal after COVID-19,’ Garcia uses Hatfield’s (2009) four types of tensions to frame her analysis of how comics creators approached storytelling to express how people experienced the pandemic’s monstrosity and relief through their mobile devices. She places the comics she analyses in their political, temporal and social contexts in order to demonstrate the universality of doomscrolling during the pandemic (Garcia 2023).

Moving forward

It is notable that these articles were produced in response to a very broad call for papers. The subjects that they engage with therefore provide limited data of a sort on the pandemic, as these aspects of communities and technologies were the ones that contributors wanted to write about. Taken together, these papers draw attention to the flexibility of the comics medium, demonstrating its suitability to convey affect and to frame deeply personal stories within a wider social context. But as befits the darkness of a pandemic moment, these analyses do not simply celebrate the strengths of the medium. Their investigations of the behaviours of comics readers and producers during the pandemic also draw attention to the limitations of comics as a creative medium and field of study: by foregrounding the ways that historical tropes, genre conventions, social structures and past beliefs inform contemporary depictions. This stresses the need for nuanced readings that respond to intersectional issues, a call to arms that speaks to the current position of both the comics industry and the academic field of comics studies. Rather than rearticulating the divisions and hierarchies of the past, a global pandemic could offer a chance to see across cultures and comics communities; to revisit historical arguments and (re)consider the much more complex origins and developments of the medium and its genres; and to make connections outside of established boundaries and borders.

As Graphic Medicine grows as scholarly field of study, there has been an increasing awareness of how early scholarly attention focused on a limited amount of comics (Noe & Levin 2020) and thus there is a need to diversify the works and creators that are analysed, as well as broader analyses of the comics creation, engagement and community. The authors of this special collection contribute towards diversifying scholarship in the field, such as the intersectional representation of health with refugee, technological, and cross-cultural experiences in the comics medium. In several authors’ efforts to bridge historical and contemporary phenomenon, they place graphic medicine in a longer and broader continuum of visual culture, while the specificities of our most recent pandemic and the comics medium, and the digital spaces they are interacted within, present unique studies of our post-COVID-19 societies. More broadly, the authors contribute to our shared understanding of the pandemic through a myriad of relatable comics experiences: as we doomscroll, contemplate lack of government action, or search for online communities in a simultaneously shrinking and expanding world.

Editorial Note

This article is part of the Conjuring a New Normal: Monstrous Routines and Mundane Horrors in Pandemic Lives and Dreamscapes Special Collection, edited by Alexandra Alberda and Julia Round, with assistance from the editorial team.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Ahmed, M. (2019) Monstrous Imaginaries: Romanticism’s Legacy in Comics. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. DOI: http://doi.org/10.14325/mississippi/9781496825261.001.0001

Garcia, S. (2023) Expressions of Doomscrolling in Pandemic Comics: How Portrayals of Mobile Technology Shifted to a New Normal After COVID-19 The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship 13(1). DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/cg.10296

Green, M. (2023) ‘“Keep it Gothic, Man”: Gothic and Graphic Medicine in Ian Williams’ The Bad Doctor’, Gothic Studies 25(3), (forthcoming). DOI: http://doi.org/10.3366/gothic.2023.0176

Jürgens, A. & Fiadotava, A. &. Tscharke, D. & Viaña, J.N. (2021) “Spreading fun: Comic zombies, Joker viruses and COVID-19 jokes”, Journal of Science & Popular Culture, 4(1), 39. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1386/jspc_00024_1

Kearns, C. & Kearns, N. (2020) “The role of comics in public health communication during the COVID-19 pandemic”, Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 43:3, 139–149, DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/17453054.2020.1761248

Krishnan, L. & Ogunwale, S. M. & Cooper, L.A. (2020) “Historical Insights on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, and Racial Disparities: Illuminating a Path Forward”, Annals of Internal Medicine, 15 September 2020. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7326/M20-2223

Malau, R.R.D, & Sirait, S.H.K. & Jeni, J. & Damopolii, I. (2021) “Using Comics to Teach the Human Digestive System: Its Effect on Student Learning Outcomes During a Pandemic” Report of Biological Education 2 (2) pp.72–80. DOI: http://doi.org/10.37150/rebion.v2i2.1418

Marini, A.M. & Fuchs, M. (2023) “Necropolitics and Pandemic Premediation in The Fall’s Neo-Western State of Exception” The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship 13(1). DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/cg.10053

Muralt, J (2021) The Fall. Collected edition. Portland: Image Comics.

Noe, M. N. & Levin, L.L. (2020) “Mapping the use of comics in health education: A scoping review of the graphic medicine literature”. Graphic Medicine [online] Available from: https://www.graphicmedicine.org/mapping-comics-health-education/ Accessed 17 December 2023.

Pizzino, C. (2016) Arresting Development. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Punter, D. (1980) The Literature of Terror. Oxford: Blackwell.

Radcliffe, A. (2023) “On the Supernatural in Poetry”, New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal 16(1), 1826: pp.145–52. http://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/english/melani/gothic/radcliffe1.html. Accessed 14 June 2023.

Round, J. (2014) Gothic in Comics and Graphic Novels: A Critical Approach. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Round, J. (2019) “Gothic and Comics: From A Haunt of Fear to a Haunted Medium”, Gothic and the Arts, ed. David Punter. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp.418–433. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9781474432375-033

Saji, S. & Venkatesan S. & Callender, B. (2021) “Comics in the Time of a Pan(dem)ic: COVID-19, Graphic Medicine, and Metaphors.” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 64(1) 136–154. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2021.0010

Saputra, V.H. & and Pasha, D. (2021) “Comics as Learning Medium During the Covid-19 Pandemic”, Proceeding International Conference on Science and Engineering, 4, pp.330–334. http://sunankalijaga.org/prosiding/index.php/icse/article/view/681. Accessed 30 August 2023.

Schneider, C.W. (2010) “Young Daughter, Old Artificer: Constructing the Gothic Fun Home”, Studies in Comics 1(2), pp.337–358. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1386/stic.1.2.337_1

Schneider, C.W. (2014) Framing Fear: The Gothic Mode in Graphic Literature. Trier: Wiss. Verlag Trier.

Smith, A.W. (2007) “Gothic and the Graphic Novel”, The Routledge Companion to Gothic, ed. Catherine Spooner and Emma McEvoy. London: Routledge, pp.251–259.

Unger, D. (2023) “Collectors, Storytellers, and Web Pros: Making Comics and Building Community During the Pandemic” The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship 13(1). DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/cg.10009

Utomo, D.T.P. & Ahsanah, F. (2020) “Utilizing Digital Comics in College Students’ Grammar Class”, JELTL (Journal of English Language Teaching and Linguistics) Vol. 5(3): pp.393–403. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21462/jeltl.v5i3.449

Venkatesan, S. & Chatterjee, A. & Lewis, A.D. & Callender, B. (2022) Pandemics and Epidemics in Cultural Representation. London: Springer Nature. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1296-2

Venkatesan, S. & Joshi, I.A. (2023) ‘“I AM NOT A VIRUS”: COVID-19, Anti-Asian Hate, and Comics as Counternarratives’, Journal of Medical Humanities. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-023-09800-6

West, K. & Jackson, K.R. & Spears, T.L. & Callander, B. (2023) “Creating Comics to Address Well-Being and Resilience During the COVID-19 Pandemic”, Health Promotion Practice, 24(1) pp.26–30. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/15248399211065407

Whatley, E. (2022) “Drawing the Invisible: Comics as a Way of Depicting Psychological Responses to the Pandemic”, The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, 12(1), pp.1–9. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/cg.6354