Eszter Szép, Comics and The Body: Drawing, Reading, and Vulnerability, Ohio State University Press, 206 pages, 2020, ISBN: 978-0-8142-5772-2, 32 b & w illustrations.

Jennifer Worth’s 2007 paper on Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2003) questions how two-dimensional images can have the same legitimacy as the living body, and how comics can come to be seen as embodied (Worth 2007: 14). Comics and the Body (2020) (Figure 1) moves far beyond Worth’s question by considering the role the body (of both the comic artist and the reader) plays in creation and interpretation. This aim is distinguished from what Eszter Szép recognises as the prioritisation of cognitive meaning-making in comics studies,1 that has its roots in Scott McCloud’s conception of closure as a mental process that takes place in the empty space of the gutter (1994: 63).

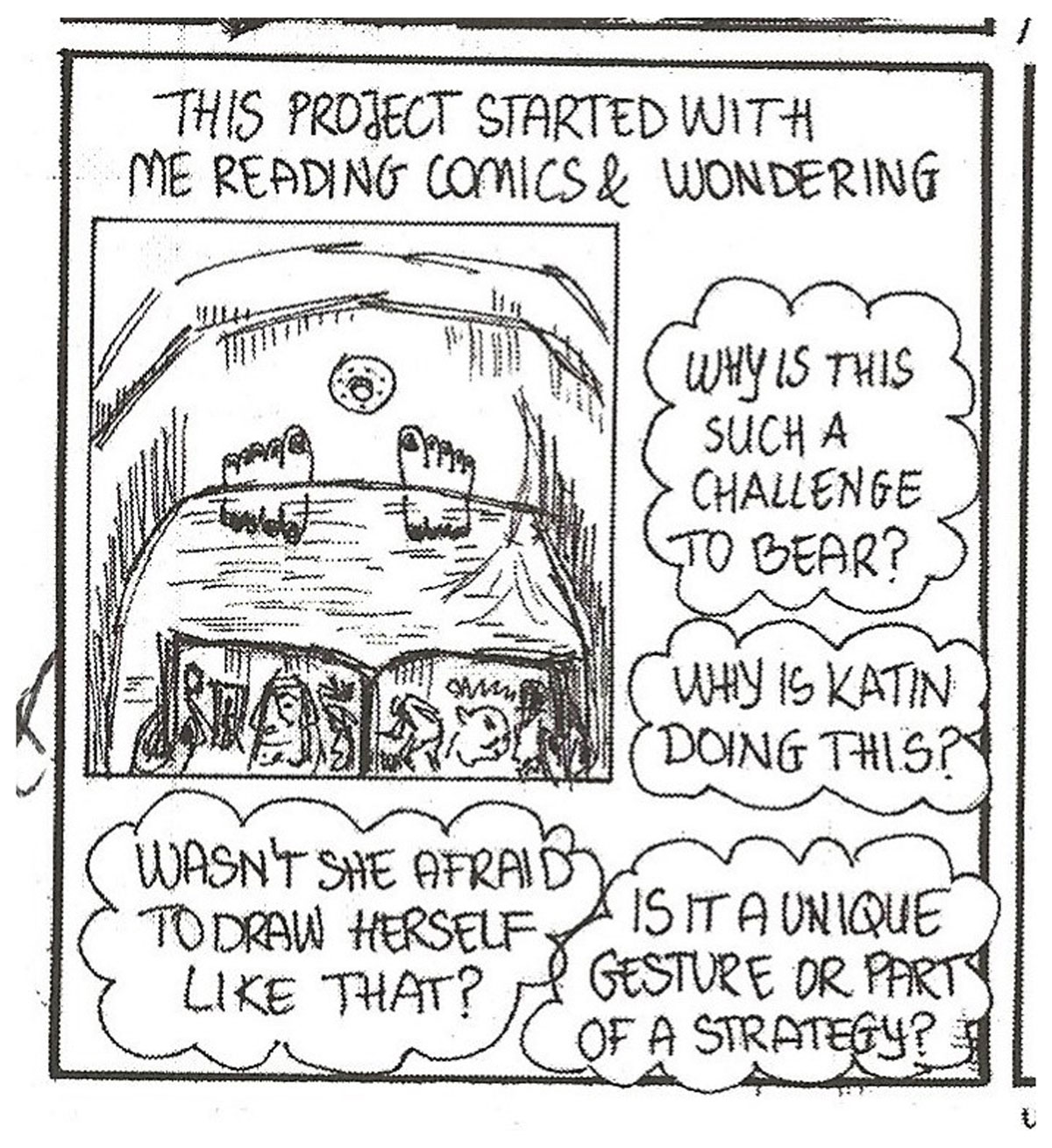

As such, it is refreshing that this monograph opens with Szép’s own embodied act of cognition, experiencing a visceral reaction to a moment of bodily vulnerability in Miriam Katin’s autobiographical comic Letting It Go (Katin 2013) whilst reading the comic in the bath, a moment that causes her to ask question such as ‘Why is this such a challenge to bear? What is happening to my body whilst reading that book, that scene?’ (Szép 2020: 1–2). What was happening to her body in this moment encapsulates the central thesis of this work, which is that non-fiction comics create a dialogue between artist and reader that is a transformative response to and exploration of vulnerability as a universal condition of human embodiment. Expanding on previous work that sees the line in comics as an embodied mark of the artist’s hand (Gardner, 2011), Szép takes this unit of the page to be the primary expressive and interpretative tool when it comes to the body and vulnerability.

In chapter one Szép examines the use of the line in the pedagogical comics of Lynda Barry, noting that she approaches the line as a form of embodied thinking that needs to be created in a relaxed dream-like state, something that is represented using elaborate spiral patterns and parallel lines of different sizes and textures. Despite this emphasis on relaxation, however, Szép notes that this bodily state is designed to create openness to an often-hidden vulnerability in order to work with and through it-a practice she refers to as ‘unlearning’ (Szép 2020: 62). Barry’s autobiographical inserts into these comics use different anthropomorphic creatures to voice her own self-doubt during creative blocks, creatures that draw stylistic reference to her other comics dealing with childhood trauma. As such Szép shows that the line links the body to its emotions, mental processes, and experiences.

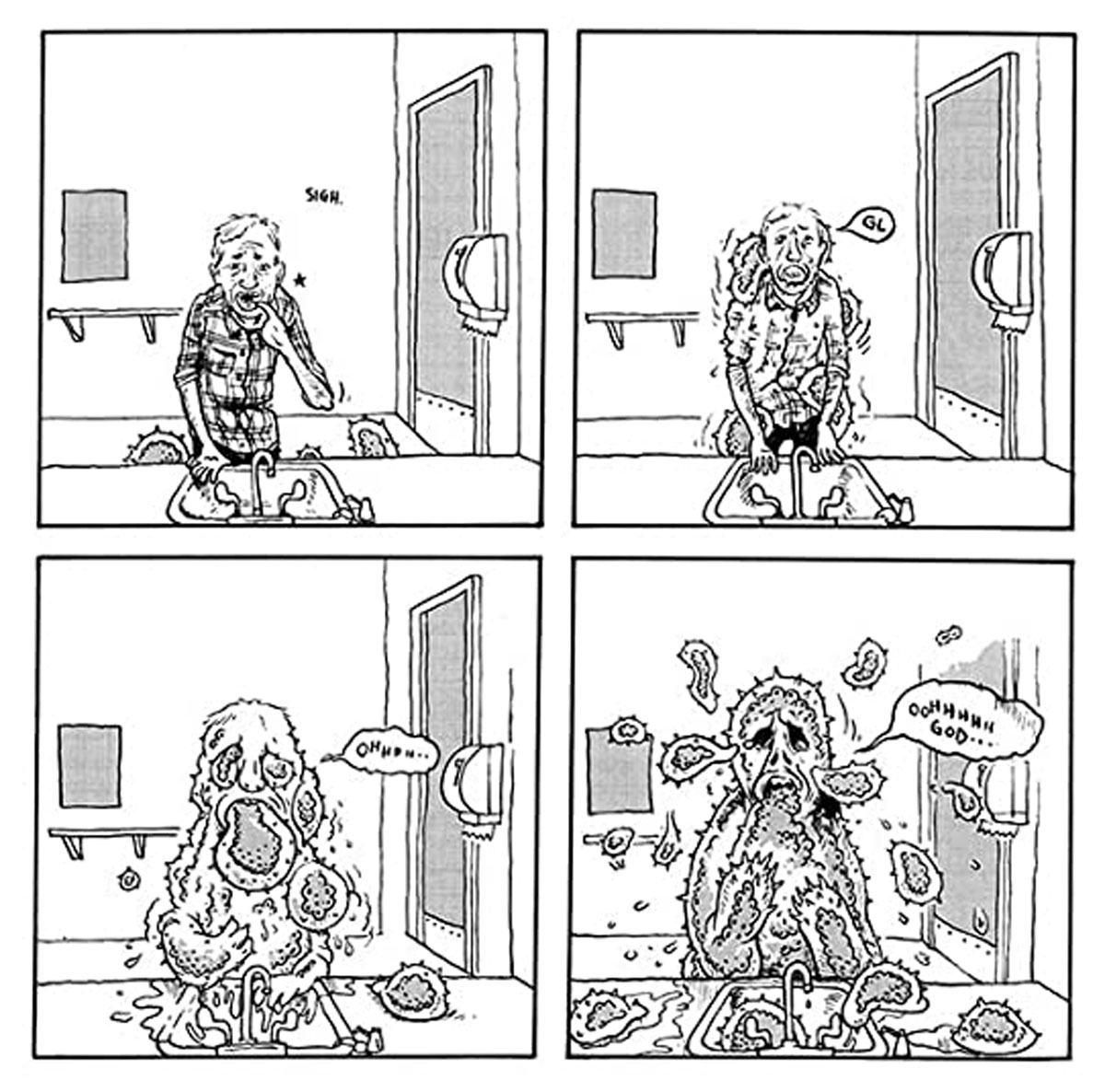

The potential for the line to transform the body and to critique certain bodily norms is explored in chapter two, with Szép providing an in-depth analysis of Ken Dahl’s autobiographical comic about him contracting herpes, Monsters (Dahl 2009). For Szép, Dahl’s constant drawing and redrawing of his body in various grotesque forms and states of transformation ‘can be read as an articulation of not only monstrosity…but vulnerability’ (Szép 2020: 80). Citing Margrit Shildrick’s Embodying the Monster: Encounters with the Vulnerable Self (Shildrick 2002), she links Dahl’s ever-changing approach to his own body to Shildrick’s deconstruction of the binary between monstrous and normative bodies, and vulnerable and stable ones-reaffirming the emphasis on universal vulnerability in this text.

Szép focuses on Dahl’s disruption of this boundary through his representation of a porous liminal skin, where the boundary between outside and inside is frequently blurred, with the virus encasing and becoming him (Figure 2). This blurring happens despite his status as ‘a heterosexual white male’ (Szép 2020: 83) -the figure against which Others (such as women or disabled people) are often marked as monstrous or vulnerable. I am somewhat sceptical of such a claim, and as such would offer Frederik Byrn Køhlert’s 2020 paper on Dahl’s other comic, Sick (Dahl 2016; under his real name Gabby Shulz) as a counterpoint to this, as it explores the way this comic reveals the process of making the taken for granted invisibility of whiteness visible through the metaphor of whiteness as illness.

Chapter three looks at the comics journalism of Joe Sacco, particularly his work on the Bosnian war. Szép discusses the presence of the body in Sacco’s labour-intensive crosshatching applied to backgrounds and surfaces, seeing it as a form of what Rosalyn Diprose calls ‘dwelling’ (Diprose 2013: 192), an interdependent relationship between people and environments. This stylistic approach mirrors the time and care spent with the subjects of his interviews, the local people impacted by the war, and in this way, drawing becomes an ethical act. Linking this to the common practice of comic artists posing for or having other people pose for their stories, Szép draws from interviews with Sacco where he discusses the difficultly of having to ‘inhabit’ (Sacco and Mitchell 2014: 65) other people’s stories of vulnerability and vulnerable bodies. Despite a visceral reaction to this process Sacco acknowledges that what he is doing is no way equivalent to what is experienced and here Szép both reinforces but also complicates the often-heavy emphasis in popular and scholarly discourse on comics as an emphatic medium by revealing it as an ethically risky and potentially unbalanced act.2

Chapter four returns to the opening scene of Comics & The Body to consider the reader’s bodily reactions and interpretation. Szép uses her own embodied reactions to Miriam Katin’s autobiographical accounts of escaping from the Nazis as a child and the legacy of that trauma, linking these reactions to theoretical work on embodied cognition. Drawing from Shaun Gallagher’s work on embodied cognition and the ‘body-schema’ (Gallagher 2006: 32) system that orientates the body in its everyday movements, Szép notes that the body can both expand to be part of something else (such as when we experience the car as our body when driving), but that in our everyday lives our own body and its processes are invisible to us, including the automatic action of turning the comics page.

Szép suggests that Katin uses different expressive and visceral uses of line (including scratchy almost completely black panels) and abject images of the body in pain or distress to make strange the automatic processes of reading and shock the reader back to their vulnerable bodies. In this way Szép’s analysis recalls Drew Leder’s theory of ‘dys-apperance’ (Leder 1990: 83), whereby the invisibility of the body is disrupted when the body ceases to function in its “normal” way, causing its radical and uncanny re-appearance. For Szép it is possible to experience this unusual interruption of “normal” embodiment because of elements on the page.

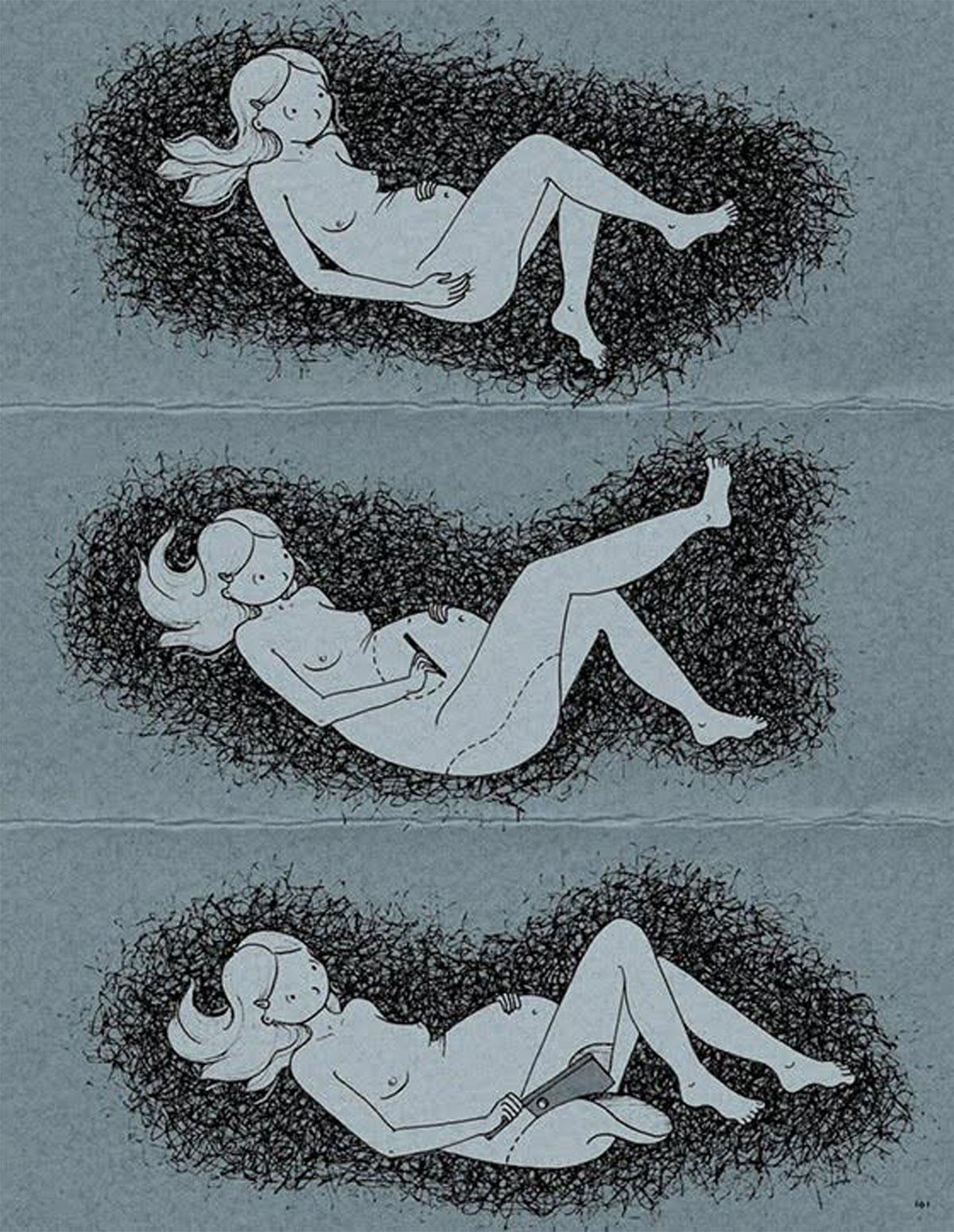

The final chapter considers how the materiality of a comic links to the body of the artist and the reader and shape interpretation. Analysing Katie Green’s autobiographical comic about her experience of anorexia and sexual assault Lighter Than My Shadow (Green 2013), Szép notes that ‘although it might seem paradoxical that a comic on the experience of having an extremely thin body is one of the heaviest graphic narratives on the market’ (Szép 2020: 167), she suggest that the thickness of the book actually creates a thematic link with Katie’s own disappearing body Whereas Green uses a scratchy black scribble or cloud that represents the subjective and overwhelming trauma of living in her body, Szép suggests that the material body of the comic is repurposed to remake Katie’s actual body. Green represents her body being cut up (Figure 3), swelling up, and being torn apart, and at one particularly vulnerable moment Katie is literally torn apart along with the pages of the book and redraws and rebuilds herself from this material, an act that implicates the reader in this moment. As Szép says of this sequence ‘it is impossible to harm the book without harming Katie’s body (Szép 2020: 172).

Szép then returns to Sacco once again with an examination of The Great War: The First Day of the Battle of the Somme (Sacco 2013) a 24-foot-long wordless comic that is printed as a single folding sheet of paper. Such a presentation foregrounds the materiality of the text in that the reader cannot read this comic in a conventional fashion and the reader will have to look closer at the text, bending over it, touching it, and spending time with it. The difficulty of moving through the text and the bodily positions one might have to occupy in order to be able to take it all in (lying across the floor with the entirety of the book spread out in front of you is not entirely viable) is linked directly by Szép to the positions of the bodies on the page (from crouching behind the trench to crawling through the mud), creating a dialogue of vulnerability between the reader and the figures depicted on the page. Interestingly, Szép shows that in this work these bodies are almost identical and become lost in the haptic details of explosions and gunfire of the battlefield, showing how they are cogs in a larger military machine.

Finally, in order to wrap up the contents of this book Szép ends with a conclusion in comics form, putting her theory into practice with the use of different qualities of line and the inclusion of her own autobiographical avatar.

Comics and the Disabled Body

I want to end this review by looking further at Szép’s approach to vulnerability and the body and its implications for disability and graphic medicine. Aside from thematic and theoretical engagement with illness and disability in this work, a further link can be found in the image of Szép reading in the bath that opens and closes the text (Figure 4). When I first saw this image, it instantly called to mind Frida Kahlo’s painting What the Water Gave Me (Kahlo 1938) something upon reading the annotations for this comic I realised was a deliberate reference by Szép. The autobiographical nature of this painting establishes this link to disability, given that the painting makes references to Kahlo’s childhood polio and her disability as a result of a streetcar accident.

Eszter Szép’s comic panel depicting her visceral reading experience that prompts many of the questions of this text and makes visual reference to the Frida Kahlo’s painting What the Water Gave Me (1938). Comics and the Body: Drawing. Reading, and Vulnerability (2020). Ohio University Press, p.184. © Ohio University Press.

Disability and vulnerability have also been highlighted and problematised by recent events. In a way Covid-19 can be seen to confirm this text’s central thesis regarding our shared vulnerability rooted in embodiment, however, in reality the pandemic has revealed how certain bodies have been classed as more vulnerable than others and yet the response to this vulnerability has been mixed. For example, six out of ten people who have died because of Covid-19 have been disabled (Charlton-Dailey: 2021)), with the risk of death from Covid being six times higher for people with learning disabilities (Clegg: 2020).

This vulnerability has been examined critically not as an inherent quality of the body but as a result of stark inequalities and prejudices made even more apparent because of Covid-19. For example, research into the significant risk and impact of Covid-19 on Black and South Asian communities in the UK has pointed to poor quality overcrowded housing, a greater likelihood of working in high risk professions, cultural barriers, and structural racism as contributing factors (Razai, Kankam, core Majeed, Esmail & Williams 2021). The greater risk for people with learning disabilities has also been attributed to higher numbers living in congregate care settings, but also prejudice (Courtenay & Cooper: 2021). An example of this prejudice at work was the reports of large numbers of people with learning disabilities and disabled people being sent do not resuscitate orders to sign in case they caught Covid and had to go into hospital (Tapper 2021). Whilst Szép does acknowledge this unequal balance of vulnerability, the question of how and why bodies become socially and politically marked is not the central concern of this work.

Szép’s use of Diprose’s conception of vulnerability being formed in dialogue with people and environments leads me to the social model of disability (Oliver & Sapey 1983), something that many disabled people evoked during the pandemic. The social model of disability rejects the medical view that disability is found in the physical impairment of a person, and instead it is inaccessible physical and ideological environments and prejudicial attitudes that are disabling-thus disabled people were not (or at least not only) vulnerable to Covid-19 because of their bodies but because of society. One disabled peer in the UK campaigned to remove the label of vulnerable from disabled people during the pandemic, arguing that ‘vulnerability…simply serves to anonymise our humanity and human rights’ (Pring 2020).

As Thomas Couser states in a critical paper he wrote on graphic medicine, the comics medium’s ability to show the sick and disabled body repeatedly across the page ‘might seem inconsistent with the aim of deflecting attention from supposedly defective bodies and highlighting disabling aspects of the environment’ (Couser 2018: 350). At the same time, he reflects on a growing critical approach to the social model, particularly from those with chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia and ME, who say that the social model denies the embodied experience of disability including pain, fear, suffering, and other complex emotions.

On the back of this observation, he critiques several works of graphic medicine that he sees as being distanced from the actual living disabled body of the artist through visual simplification, bodily metaphors, and anthropomorphism, something that he argues sanitises illness and disability. Whilst the potential for comics to individualise, sanitise, and create distance is something I have discussed in my own work, I do not fully agree with Couser’s statement here. Bodily metaphors in comics do have the power to comment on societal norms and lived experience, and there is also a risk that close attention to details of disabled bodies might encourage voyeurism and spectacle. Similarly, I believe Szép’s bodily focus can go someway to addressing the criticisms of the dogmatism of the social model.

In conclusion Comics & The Body plugs something of a gap in comics studies with its focus on cognitive meaning-making and evokes many interesting questions for areas such as graphic medicine, trauma studies, and disability studies. I also believe Szép’s methodology could be used to address two questions and concerns, the first a point of interest for myself, and the second outlined by Couser. Firstly, her focus on the body of the reader could be brought to bear on how different types of bodies (including disabled bodies) might interact with comics. Finally, Couser’s interest in comic artists whose impairments impact their quality of line such as Peter Dunlap-Shohl in My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s (Dunlap-Shohl 2015) is certainly one I think Szép would be well placed to address, In fact, a recently published Hungarian article by Szép on John Meir’s autobiographical comics concerning his MS (Miers: 2019) suggests this is a question she may already be thinking about. As such, I am excited to see the work she produces next.

Notes

- Ian Hague’s Comics and the Senses: A Multisensory Approach to Comics and Graphic Novels (2014) is a notable exception to this, although this focuses in the senses in isolation. [^]

- One text that does this in more detail is Kate Polak’s Ethics in the Gutter: Empathy and Historical Fiction in Comics (2017) (Szép cites both this and Hague’s book in her introduction). [^]

Author’s Note

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material under educational fair use/dealing for the purpose and criticism and review and full attribution and copyright information has been provided in the captions.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Charlton-Dailey, R. 2021 Please Stop Killing Us. The Unwritten, viewed 19 July 2021, https://www.theunwritten.co.uk/2021/02/14/please-stop-killing-us/#more-326

Courtenay, K. and Cooper, V. 2021 Covid 19: People with learning disabilities are highly vulnerable. BMJ. Volume 374, Issue 1701. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1701

Couser, G. T. 2018 Is There a Body in This Text? Embodiment in Graphic Somatography. a/b: Auto/Biography Studies. Volume 33, Issue 2. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/08989575.2018.1445585

Dahl, K. 2009 Monsters. Palm Springs, CA: Secret Aces.

Diprose, R. 2013 Corporeal Interdependence: From Vulnerability to Dwelling in Ethical Community. SubStance. Volume 42, Issue 3. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/sub.2013.0035

Gallagher, S. 2006 How the Body Shapes the Mind. Oxford: Clarendon Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/0199271941.001.0001

Gardner, J. 2011 Storylines. SubStance. Volume 40, Issue 1. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/sub.2011.0008

Green, K. 2013 Lighter Than My Shadow. London: Jonathon Cape.

Hague, I. 2014 Comics and the Senses: A Multisensory Approach to Comics and Graphic Novels. Abingdon: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315883052

Køhlert, F. B. 2020 “A Grotesque, Incurable Disease”: Whiteness as Illness in Gabby Schulz’s Sick. Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society. Volume 4, Issue 2. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/ink.2020.0018

Leder, D. 1990 The Absent Body. London: University of Chicago Press.

McCloud, S. 1994 Understanding Comics: The invisible Art. New York: HarperPerennial

Miers, J. 2019 So I guess my body pretty much hates me now. London: Comics Hub/University of the Arts London.

Oliver, M. & Sapey, B. 1983 Social Work with Disabled People. New York: Macmillan.

Polak, K. 2017. Ethics in the Gutter: Empathy and Historical Fiction in Comics. Columbus: The Ohio University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv16x2b4t

Pring, J. 2020 Coronavirus: Peer calls for an end to use of ‘vulnerable’ to describe disabled people. Disability News Service, viewed 17 June 2021 https://www.disabilitynewsservice.com/coronavirus-peer-calls-for-an-end-to-use-of-vulnerable-to-describe-disabled-people/

Razai, M. S., Kankam, H. K. N., Majeed, A., Esmail, A. and David, W. R. 2021 Mitigating ethnic disparities in covid-19 and beyond. BMJ. Volume 372, Issue 4921. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4921

Sacco, J. and Mitchell, W. J. T. 2014 Public Conversation. Critical Inquiry. Volume 40, issue 3. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/677330

Shildrick, M. 2002 Embodying the Monster: Encounters with the Vulnerable Self. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Szép, E. 2020 Comics and the Body: Drawing, Reading, and Vulnerability. Columbia: The Ohio State University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.26818/9780814214541

Tapper, J. 2021 Fury at ‘do not resuscitate’ notices given to Covid patients with learning disabilities. The Observer, viewed 19 July 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/13/new-do-not-resuscitate-orders-imposed-on-covid-19-patients-with-learning-difficulties

Worth, J. 2007 Unveiling: Persepolis as Embodied Performance. Theatre Research International. Volume 32, Issue 2. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0307883307002805