About Nick Sousanis

Nick Sousanis is an Eisner-winning comics maker and an Associate Professor of Humanities & Liberal Studies at San Francisco State University, where he started a Comics Studies program. His book, Unflattening (2015) won the Lynd Ward Prize for Best Graphic Novel, the 2016 American Publishers Awards for Professional and Scholarly Excellence and was nominated for an Eisner-Award in the Best Scholarly/Academic work category, among other numerous accolades. His other works include “Against the Flow” and “Upwards” in The Boston Globe (2015a), “The Fragile Framework” for Nature in conjunction with the 2015 Paris Climate Accord co-authored with Rich Monastersky, and “A Life in Comics” (n.d.) for Columbia University Magazine. He is currently working on his next book, Nostos to be published by Harvard University Press. See more at http://www.spinweaveandcut.com or on Twitter @nsousanis.

The Interview

This conversation was conducted over email and subsequently edited. KS stands for Kay Sohini, the interviewer and NS stands for Nick Sousanis, the interviewee.

KS: How do you begin a piece? I know that you do not work with a script, so I am curious about what your workflow looks like.

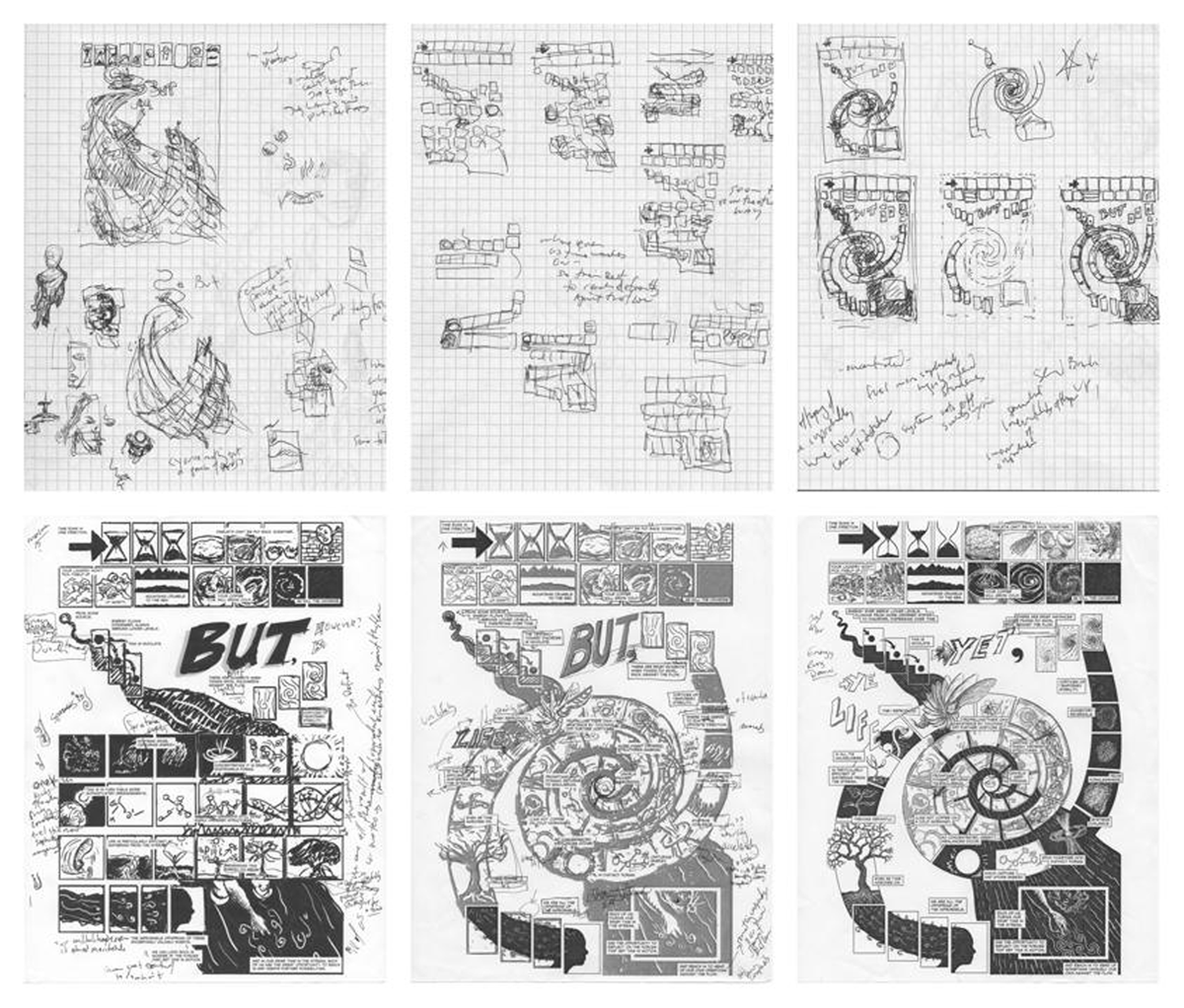

NS: I always begin with something I’m curious about – some ideas or information that I want to make sense of for myself. From there, I typically move to large, cheap newsprint paper and try to put down all the things I’m thinking of – as sketches, in words – and then start organizing ideas with arrows and other graphical notation. I may make successive versions of this as it overflows and new ideas occur, and with them better ways of organizing it all start to emerge. If it’s something that I don’t already know a lot about (which is often), I’ll start digging into readings and see where that takes me. This may proceed by itself or maybe that will quickly lead to new iterations of my sketchmaps. There’s a lot of back and forth as things take shape. At some point the sketches are too numerous and are a bit overwhelming, so I’ll type things up from them into an outline of sorts. It’s a lot easier to keep track of ideas and search them in a text document so I’ll synthesize things from all the different sketchmaps into this. Then I’ll probably annotate and draw on the printed outline as well and use this to generate new sketchmaps.

Eventually, I’ll feel things have reached the point where I can start in on a chapter. This will require a new set of sketchmaps detailing the breakdown/thumbnails of the chapter (this too, may mean a bunch more research as I’m getting deeper into the subject matter). With that, I’ll expand the text outline to accompany the chapter, and more back and forth between these. When I’ve got the beats per page in acceptable form, I can finally start the pages! And then I switch over to my notebook. I design pages on gridded paper, which helps me keep things straight and scaled correctly, since it’s more about architecture of the page than nice drawings. Here, I’ll work out the exact movement of forms on the page and reading flow. And then, and only then, I’ll start in on the first page of the chapter and proceed sequentially from there, repeating the design process as I get to each new spread. This means doing layout in photoshop, sticking in bits of text from my outline and notes, and then playing with how it all flows and where it fits. The latter involves enormous amounts of cutting and finding very specific words to serve my purposes – and as few of them as I can. (Working in comics forces me to be a better editor for myself than I am in writing – as evidenced by my lengthy responses here!) Now, I’m working on specific drawings – which often means a ton of research on the things I’m drawing, so I have to dig up a ridiculous number of images to work from to get the information right on the page. Frequently even at this point, I realize something through my drawings that I realize I don’t understand in the research or feel I need to know more about, so I start reading again – and that may shift things even for a tiny element on the page. But eventually things fully congeal, and I get closer to final drawing and tight inking, and firm up exactly what words stay and where they go. And then maybe I finish the page. I know when I’m done (or nearly so) when I want to look at it for a long stretch and just enjoy moving through it and am pleased with how it all works together. Before that, it might be acceptable, but not so pleasing – so I know I must push through. It’s a long process!

KS: I hear you and I think I empathize with that. I tend not to work from a script either, since my work is so heavily reliant on images, so my process usually involves a LOT of trial and error. It is time-intensive, but this is exactly what makes the process so educational to me as a creator, so I suppose this method has its pros and cons!

Coming to the next question, I think it has been nearly six years since Unflattening was published. Going by the responses on Twitter, it seems that every few months, somebody or the other comes up with a new interpretation of what the book is doing. Is there a particular interpretation that took you by surprise, something that you didn’t think of at all, not even peripherally, while drawing Unflattening?

NS: Yeah, this has happened a lot – and somehow, I’m still surprised by it! My approach in using metaphor and stripping out terminology that ties the meaning to a particular field was always intended to allow people to approach the work from wherever they happened to come from and find their own way in. I noted this experience early on in my doctoral work, after making a comic as a chapter for my advisor Ruth Vinz’s book on doing narrative inquiry (Sousanis, 2011). This piece used the metaphors of drawing and seeing to get at the research process. And what I found is the background of the reader greatly affected what they thought it was about. Some would say it was a comic about drawing, some on seeing, and others (usually academics) saw it as a piece about research. They were all correct – which was exactly what I’d hoped! It meant something to each reader, and the core idea still came through, but they could own the meaning from their particular perspective. It’s a tricky dance of language – finding words that mean precisely what I want, but still with the ambiguity to have multiple meanings. My favorite question that teachers ask students when teaching Unflattening: what’s it about? Responses are far and wide. To me, it’s a book about education and learning (and comic books) but people apply it to their experiences in so many different ways – and I’m always geeked when I see students come up with new ways to apply it to something in their own experience. Generally, I suppose the business-related responses are the most surprising. I spoke with the Well-Read Investor Podcast, Unflattening made a list of best books on innovation for entrepreneurs, it’s been used in workshop facilitation, and someone recently described it as a “meditation on non-fungibility” – which I’m still not clear on what that means, but that’s great by me!

I’ll say one more thing on this – my approach came from the political comics I made before starting my doctoral program. I wanted to get away from comics that said “ra-ra!” for our side but do not reach people who don’t already agree with you. How can we connect to people and have them stay with a conversation longer and see themselves in what you’re talking about? For me, using metaphorical imagery and stripping out some of the language barriers that we build up between ourselves was the way at it. It can make my work difficult to classify but I’m great with that. I’m difficult to classify – we all are! Why shouldn’t our works reflect that complexity?

KS: Absolutely! You recently posted about how drawing the first chapter of Nostos involved some thirty or so pages of annotated sources. It was incredible to see the amount of work and research that goes into one chapter. I guess this question comes from my own creator anxiety, but how do you (if you do) make sure that a detail that you worked into the page painstakingly is visible to the reader?

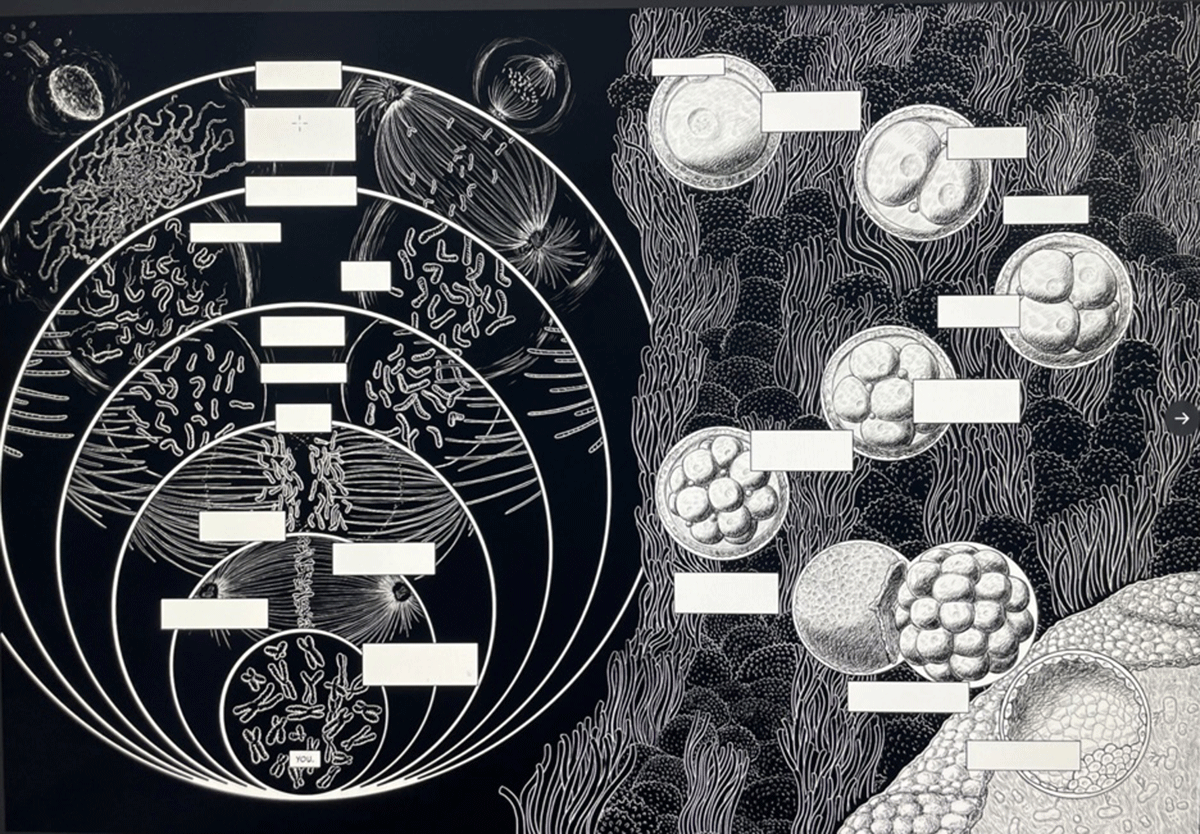

NS: Yeah, that chapter was nutty – I didn’t know a lot about not-yet-born babies and newborns (at least outside of lived experience) and now I’m overflowing with things I could tell you about this time. Most of this is invisible to the reader or at least to most readers. The key for me is to get everything as correct as I possibly can – this applies to the information and the drawings (not that we can separate them out) and often as much in what I don’t show. It’s true, the average reader won’t know the difference in a lot of what I put on the page, but there will be readers that do – and they matter to me. I think about this in terms of things from nature that I draw, for instance. My mom is a naturalist – so when I draw a spider or a bird or something, I draw a specific one that makes sense with the environment I’m placing it in, and all of that. I’m quite aware that my mom will know if it’s not right! But I think this can be applied broadly to at least the kind of comics I make. And it’s interesting in doing the research – so often drawings and diagrams I find to use as research are wrong or missing something. And I only know because I’ve looked at and read so much of the literature that I start to notice discrepancies and I have to figure out what should be. So perhaps I need to get it right in case the work is used by other people. But I always find that if I do all I can to get the specifics correct, then that leads me to making better work. And thinking again about the people who don’t know the difference initially – I think that it invites them to reread and discover new things. I’ve heard from readers of Unflattening who read the notes and then the book all over again as if a new experience. I like the idea of layering so much meaning on the page that you can keep coming back to it to make new discoveries. And all of this speaks to your question above – to the science person who reads it, the book is a slightly different thing than the person without that background. To someone who works with babies or is a recent parent, they are going to have a greatly different appreciation of my chapter on babies than someone farther from that experience. But it has to work for both.

KS: This is a thing that I find fascinating about drawing nonfiction comics—one must read and refer to so much to draw just a couple of pages. It’s a really involved process. But both as a maker and a reader, finding the connections can be very rewarding.

Speaking of making and finding connections, I feel like there’s some sort of a creative-intellectual expedience in trying to make the medium work for you. I only ever managed to solve a Rubik’s cube once in my life but working out the layout and the composition of a comics page often feels like that to me: like I just solved a Rubik’s cube without a YouTube video. I suspect that the finished pages do not really convey this. Do you have a method to document your process, a behind-the-scenes of sorts?

NS: Ha – I’ve never solved a Rubik’s cube – so my hat’s off to you! I’m going to make a slight tangent here – I get asked periodically if I find a connection between my comics-making and my mathematics background. I struggled a bit to answer that early on, besides some of the mathematical subject matter that I inevitably weave into my work, but as I’ve reflected on this more over the years, I see deep connections between how I learned to write proofs and how I construct pages. I had some fantastic mathematics professors back at university, who were both creative and extremely clear in demonstrating their thought process – and in impressing upon us how important this is. My proofs professor, who I’m still in touch with, stressed how clearly the work had to communicate what you’d done and how aesthetically beautiful that organization could be as well. There’s something very satisfying about finishing a proof where the pieces all have come together in this neat way, as if it was always obvious. But, not so unlike a comics page, when you start – you don’t know where you’re going, you have to feel your way through it and start to build some sensible structure to help you find your way. And once it’s there, you refine it so it’s shareable to others. I’m not sure I would recommend a proofs course for all comics artists (!) but there’s something in that that I think would be greatly beneficial, and the more I reflect on this, the more I want to make a comic making parallels between proofs and comics-making.

To your specific question on documentation – I save everything. I only work on my comics designing in my newsprint pages and my gridded notebooks (if I sketch something elsewhere, I redraw it in one of those for continuity) – and I date all of it. I’m a little sloppier with printouts of the pages in process that I then draw on, but it’s usually easy enough to figure out. I’ve also loved seeing process, and often been as interested in that as the finished product (this is true as well in mathematics…). When I ran a university art space back in Detroit – I put on exhibitions that looked at the process at the same time as exhibiting final works (Sousanis, n.d.). Early on when I would talk on my comics work, I’d share a few images of my process and see people really light up in response. I find that if you don’t have experience creating a kind of thing, the finished product looks like magic – like it just arrived out of the creator’s head fully formed. But the truth is it’s never like that – and so I think getting access to the thinking behind it both makes the work richer, but more importantly it shows people how they might find their own way into making works of their own. So, I’ve kept sharing more of the behind-the-scenes stuff – I’m way too slow and can’t work on my work frequently enough to do time lapse or some other kind of video of my process (Figure 1). But I can collect it all since I design everything on paper and organize it and keep making more of that available. A thoroughly documented example can be found on my website.1

KS: This is amazing! Thank you for sharing. Last Spring, when I audited your Comics and Culture class, you introduced us to the De Luca effect. We looked at Gianni De Luca’s rendition of Hamlet, and several derivations such as the one from Nightwing. Since then, I have used the effect in at least 3–4 of my own pages, each time a little differently than the last because this medium is so endlessly generative. What are some formally rich works that you find yourself going back to when you are looking to be inspired?

NS: I’m glad that had such an impact on you – and have really enjoyed seeing what you’ve created deploying that approach! What I do in classes really feeds my work (and to a similar extent, things I try on my pages, give me ideas for things to do with students). I gather a ton of interesting examples to share with students so we can explore how that affects our approaches to storytelling – what does a different ordering principle let us say in ways we couldn’t with something different? For instance, I got curious about hexagonal grids on pages2 – and started trying to find what I could (there aren’t a lot as it’s hard to make reading order with hexagons – easier for maps). I then thought about circles as an ordering principle, and with some social media crowd-sourcing – came up with tons of examples for class (I put all the examples that I collected up on my site). As I started the new book, I decided that each chapter would have a particular organizing constraint for the overall composition. And here I had this resource of circular compositions handy3 ! Right now, I’m in the midst of drawing that chapter where every page is somehow using circles as integral to the layout. A good challenge, but also tied into my subject matter (at least that’s what I tell myself).

As for particular authors – sure, I keep a lot of things within reach, the various works of Alan Moore and collaborators, JH Williams, Frank Quitely, Marc-Antoine Mathieu, Kevin Huizenga – authors who pay great attention to the formal structure of their compositions. But at the same time, I draw on anyone – often reading My Little Pony comics with my daughter, I’ll see an example of some neat use of the page that I take a snapshot of for class, and my own mental reference. Comics authors are always trying to solve problems on the page and the solutions they hit upon are important to have on hand when you’re trying to tackle your own challenges. In fact, my daughter and I just reread one of our favorite comics ever – a short Uncle Scrooge & Donald Duck comic by Don Rosa called “A Matter of Some Gravity.” It’s this brilliant story where the ducks are magicked so as to experience gravity as if horizontal – but only for themselves, everything else is normal. As the story unfolds, they have to figure out how to navigate the world (and save Scrooge’s Number One dime!) in increasingly ridiculous fashion. But what Rosa does from the first page – even before the spell has been cast – is organize the page split top and bottom And then when the spell is cast, the upper grid is the normal perspective, so Scrooge and Donald are sideways in it, and the lower half is always devoted to the duck’s point of view, so they are right side up for the reader, but everything else is wrong. It’s a brilliant choice, and in organizing it that way Rosa really teaches you how to read the comic, and I think that’s a big thing in all comics – building into the architecture the ways you want your reader to approach it. In my teaching (and certainly in my work) I really emphasize the importance of constraints to aid in the creative process (frequently drawing on the work of Matt Madden, whose 99 Ways to Tell a Story (Madden, 2005) I think is an essential text for anyone looking to make comics) – and this applies to comics of all kinds!

KS: The circular compositions from Nostos that you have been sharing on Twitter are a sight to behold. And comics that implicitly teach you how to read comics are my favorite kind (Figure 2). Like Unflattening! I am going to take this opportunity to ‘formally’ ask you a question that I feel like I have dropped in your DM at least a handful of times since I started “Drawing Unbelonging.” Your answer has bailed me out of several creator’s blocks since 2020 so maybe it will help whoever is reading this too: What would you tell somebody who is stuck, or somebody who is just starting to draw comics?

NS: To those who are stuck whether as a comics maker or really any creative endeavor – I’d say get a big sheet of paper and start making marks on it. Whatever comes to you, get your arm moving and your eyes starting to make connections. Things will start to reveal themselves and congeal as you go. It’s a lesson I believe in strongly and yet still have to relearn frequently. I was stuck on the new book for a long stretch – and I kept trying to read and think myself to a solution. It kept not working. I had a ton of the ideas figured out, but not the frame that made it feel like my work. And then finally I got out my big sheets out and started going – and all these ideas simply poured out onto the page – and I was making connections at a rate I couldn’t quite fathom and was surprising myself as I went. And then things made sense – and I could do the other work – the refining to turn it into something shareable. What’s frustrating is that I know this – but the habits of thinking as an internal activity of stillness are hard to let go of.

To the person just starting to draw comics – I’d say draw comics on whatever you feel like. Start short – make one-page comics, two-page comics, and mini-comics. Give yourself a constraint of length so that you can say – I finished a comic, and then get going on the next one. Read lots of comics so you can start to identify solutions to things you’re trying in your own comics, and that as you become a better reader of comics that expanded vision is fueling you to become a better maker.

KS: Yes! Personally, whenever I am stuck, I read and then I read some more till I magically have ideas and an inclination to draw again. I remember reading The Secret to Superhuman Strength (Bechdel, 2021) the very week it came out, and then moving to my desk in a daze and thumbnailing a whole chapter without really thinking about it. Bechdel is something else. She inspires me to create in a way that I don’t quite understand but I am very grateful for, nonetheless. What was the last thing you read?

NS: I regularly get things from the comic shop (the awesome Comix Experience here in SF!), continuing a weekly ritual I’ve been observing since I was like twelve (though not always so weekly now). While I don’t talk much about them, this still includes superhero comics. In part, this is due to a general soap opera-like concern for the health and well-being for these characters whose lives I’ve been reading about my whole life, and beyond that, the genre attracts some tremendous authors whom I both enjoy and offer a lot of inspiration. On that note, Nightwing #87 – drawn by Bruno Redondo and written by Tom Taylor – a continuous sequence stretching across all 22 pages of the comic utilizing the beforementioned De Luca effect (Redondo and Taylor, 2021). Really terrific example of something that can be done in comics, brilliantly executed. Kelly Sue DeConnick and Phil Jimenez’s long-awaited project Wonder Woman: Historia (Sue DeConnick and Jimenez, 2021) was brilliant in its world-building, mythology reimagining (akin to The Sandman a generation prior), and a tour de force of drawing and composition from Jimenez. All around an ambitious, glorious, breathtaking achievement! Having been a kid reading comics in that seminal year for comics 1986, this feels like it has the potential to spark a similar enrichment of what authors might aspire to in mainstream comics. The past two years I’ve been picking up books that I really want to read, but rarely get around to reading (outside of all that I read with my kids). But more recently I pushed myself to read even if only a little bit each night, so 15 minutes or so at a time, I’ve been getting myself through a few of these (and so many to go!). Gene Yang’s Dragon Hoops (Gene Luen Yang, 2020) was so good! I teach his essential work American Born Chinese (Luen Yang, 2006) frequently, and this feels like a whole other level of masterful storytelling and cartooning from Yang. Even knowing the account was a true story, while reading it, I was still on the edge of my seat and in disbelief with what I read. He held together so many layers of complexity – including his own approach to and struggles in writing nonfiction/memoir and I think it’s incredibly informative for others looking to make this sort of work. Alison Bechdel’s The Secret to Superhuman Strength (Bechdel, 2021), as you mention, was an absolute delight – a word perhaps not often associated with her work, and as always incredibly smart storytelling making full use of the form! The use of a broad color palette was wonderful and quite welcome. It was great too to get sort of sideways views of some of the stories from her other memoirs – it’s richer knowing her whole work and seeing how this informed readings of those, and the different narratives she moved between, each speaking and informing the other was quite brilliant. Additionally, as someone who was an athlete and made my living teaching tennis up until the end of my doctoral program, it was great to see sports and athletic activity in general taken up in comics – to more such!

I’d never bought a Ninjak4 comic until this past year, but I never miss a chance to read a comic drawn by Javier Pulido! Pulido’s style feels somewhere between homaging Ditko and abstraction, and this was a master class in page composition, design, and color – there’s so much to learn from in all that he does on the page! His two-page spreads in particular were fantastic – truly innovative approaches to composition, carving up the space in unique ways, and they all worked. Pulido did a few blog posts on his process that I know I’ll draw on for myself and students. The other work of recent note, is Friday Book One drawn by Pulido’s compatriot Marcos Martín, another artist I will pick up anything he’s drawn, and written by Ed Brubaker. It’s a gorgeous, clever, and engrossing tale – and the sort of mystery story I’d read with my seven-year-old, if not for some more mature content. Martín shines in composition and design, as always – and some absolutely stunning figure drawing (I loved the glimpses into his character designs at the back as well). There are so many great books out all the time – I really can’t keep up even knowing about them, let alone reading them. A good problem to have!

KS: I am taking notes! The Nightwing sequence you mention is absolutely stunning. And yes, time is a such a sneaky little thing. In “Comics in and of the Moment,” we wanted to emphasize the “of the moment” aspect of comics responses. I think because of the Graphic Medicine-centric comics we saw in the wake of Covid 19, I forgot that certain comics take longer to draw, so we had to extend our deadlines for several of our contributors. I see two types of comics/graphic scholarship: first, the kind where, if you take out the images, the text remains perfectly coherent in and of itself; second, the kind where the text and the image make meaning interdependently. Personally, I find the second more rewarding, but without talking heads, or without illustrative images one constantly must find new ways to express ideas. I believe that we need more graphic scholarship everywhere, but the time-consuming nature of the latter kind concerns me a little as a creator. I love the mostly non-illustrative route I took in “Drawing Unbelonging” but I keep thinking that there are finite hours in the day and that I can’t possibly keep it up!

I am not sure that there’s a coherent question in there. I guess I am just wondering what your thoughts on illustrative comics are, versus comics as the thing itself, and how time constraints factor into that equation. Not that the two cannot overlap.

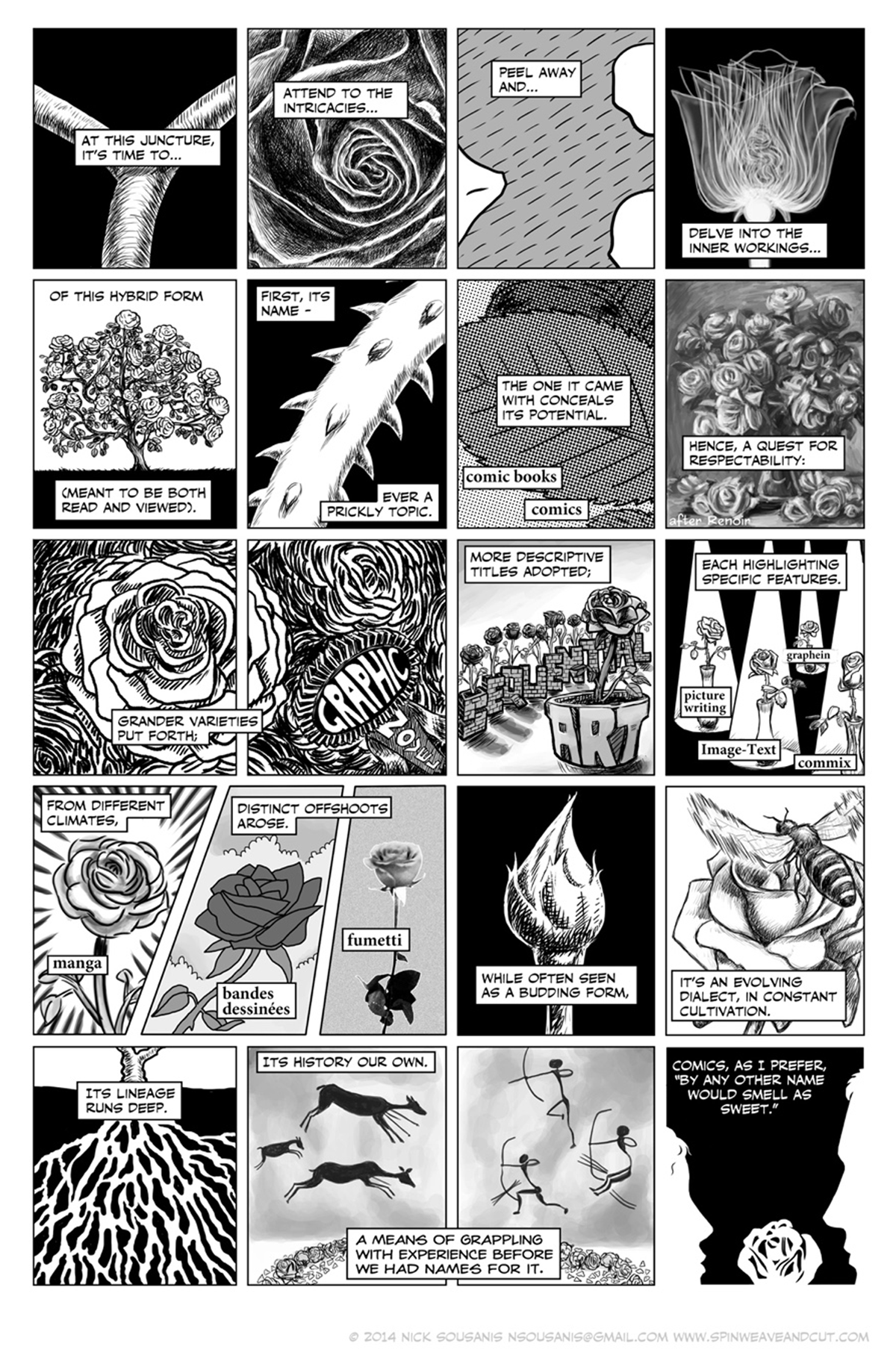

NS: I have a pretty strong bias here. When I returned to full on making comics as an adult (political comics around the 2004 US Presidential election), that first comic I made looked a whole lot like a Scott McCloud comic – there I was, sitting at my drawing desk, narrating the essay. And that was fun and productive (I still like it) – but Scott already did this and does it so phenomenally well! When I did the follow up comic, just two weeks later (the initial one was prior to the election, the second right after), I knew I wanted to find something different, and took inspiration from Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie’s “This Is Information,” (Moore and Gebbie, 2002) from a 9/11 anthology. It’s a great short comic essay using visual metaphors to get at some deep issues around the tragic events. This sparked my thoughts on using visual and verbal metaphors to get at my ideas – and I’ve been following that trajectory ever since. This second comic, titled “A Show of Hands” (Sousanis, 2004) was about voting, and for this grid-based comic each panel had to have something to do with a hand. The constraint was liberating and generative (besides fueling my approach generally, I’ve done some specific pages/short comics using a similar tight constraint (perhaps most significantly the “Rabbit” page5 from my game comic and the “Rose” page6 in Unflattening), and now have made it an exercise in my classes (Figure 3).

The “Rose” page. Unflattening © Nick Sousanis, 2015.

What’s wonderful about the comics form, and one of the joys in teaching comics, is how vast approaches to making comics are! Comics can be richly illustrated, they can have the most minimal of pictures, they can be text-heavy or wordless. There are all these different axes and a spectrum of choices in between and I feel everyone can find their way into comics. The reason I start all my courses and workshop with my ‘Grids and Gestures’ (Sousanis, 2015) comics-making activity is, partly to show people how much they know about drawing even if they claim they can’t draw, but more so I think it opens up possibilities for how one can use the page to organize your thoughts that won’t happen with an activity that says make a grid of six panels on a page and then draw in them a sequence of events in your day. That’s not to say that’s bad and someone won’t learn something, but they won’t be nudged to see greater potential on the page and in themselves. And I see this so much in my students – some who come in drawing wonderfully, and some who never really demonstrate great prowess of craft but still find profound ways to get their thoughts down on the page.

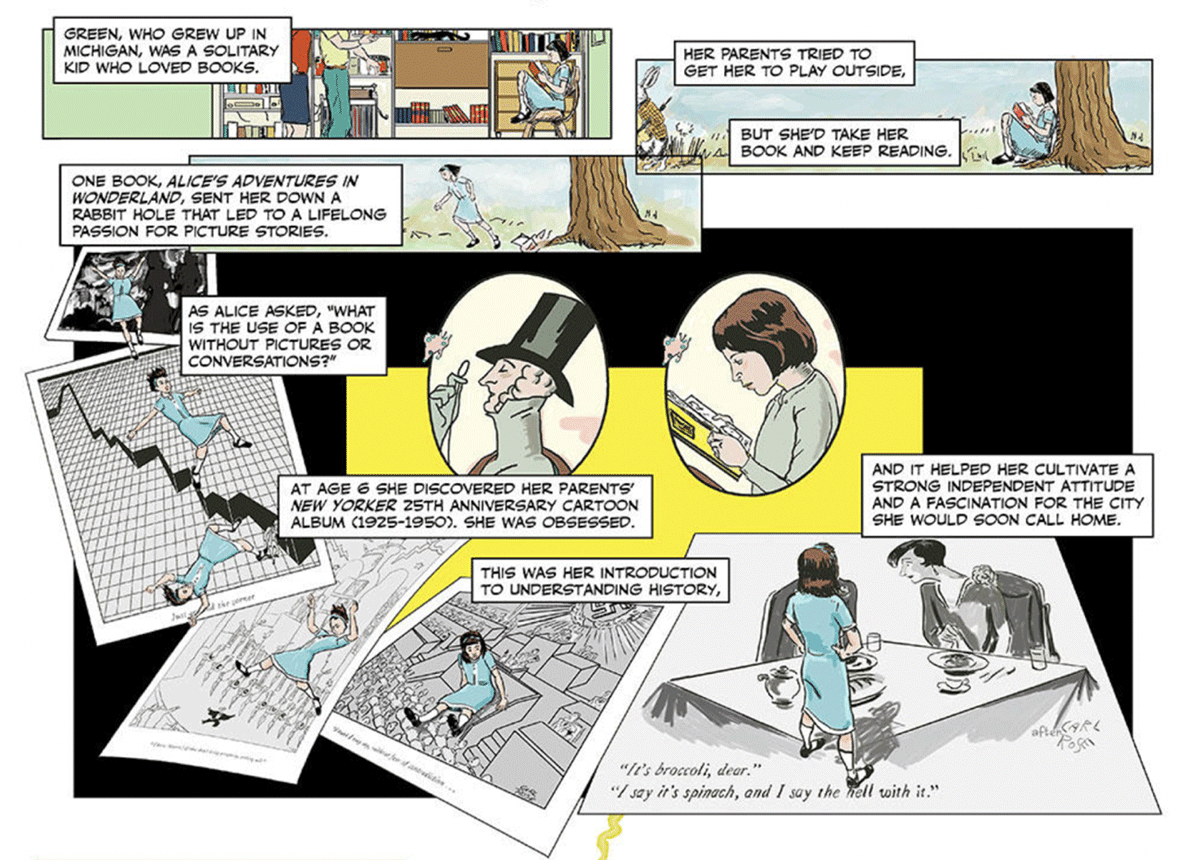

One way I look at the impact of Understanding Comics (at least for me) (McCloud, 1994), is that it showed how expansive comics can be and offered people handholds for finding their own way into them. And I think the mistake some have made is to see what McCloud did as The Way to make educational/informational comics. It’s a way, it’s his way – and he rocks it. But what else can we do? (And this I really think is his closing message in the book – it’s an invitation to find our own way of making comics and add to the conversation of all that comics can be.) When I was approached by Nature to do the comic on climate change for the Paris climate talks, one of the first things I told them on the phone call with my eventual co-author (the wonderful science journalist Richard Monastersky) and the editors was that if they wanted me to draw a scientist or journalist walking around explaining things, I was the wrong person to do the job. Despite that, they still went for it – and it was a tremendously difficult project – for me, but also for my co-author. I know that they had anticipated giving me a script of scientific information to include on each page, and instead it was this enormous thing where I had to learn all of the science so I could start to develop some organizational structures to make sense of it all and manage it in the short space that we had to work with. This was pretty similar to my response to initially being offered the chance to make a comic for Columbia Magazine on my friend comics librarian Karen Green (for which I ultimately won an Eisner award for best short story (Figure 4)). I said no – not really the sort of thing I do or do particularly well. When they circled back to me a few months later, I said I’d see if I found an approach that matched how I worked, otherwise still no. And then with a weekend to think about it, something occurred to me from my teaching – I get students to follow “Muses” – work in styles of authors they want to emulate and learn from, and so I got super excited to make a comic on Karen through the comics that she loved to read.

That was something different and far more compelling to me than drawing a straight narrative of her life. It gave me an opportunity to learn and to play and push myself to try things I’d never done before (figuring out how to make an Al Jaffee-esque Mad Fold-In using words that Karen actually said that also made the point I was trying to close with was perhaps the hardest thing I have ever attempted). None of that says there’s anything wrong with a more straightforward approach (and honestly, I know there are plenty of readers who prefer it – it can certainly be more accessible and easier to get into what you’re reading), it’s just not mine, at least not now. And absolutely, as you point out – these tend to be more difficult and significantly slower to make. As I describe my own work – I have no characters, no story really, no avatar of myself or something to draw each time – so I’m always trying to figure out what metaphors I’m using, what kinds of imagery will I draw, and how the reader will experience it on the page. It makes me a not particularly nimble comics author, which is something I’d like to be – I marvel at watching my students do things so quickly, and hopefully that will rub off on me someday. :)

Ultimately, I’m not going to tell anybody how to make comics (I don’t even tell my students, I just give them things to try, and they figure out their own path) – that’s a question each of us has to figure out for ourselves. But I do think exploring all that comics have to offer, getting a grip on the different affordances that they make available, and seeing which ones resonate with each maker’s particular perspective can lead to inventing rich and generative ways of working. Comics are vast and offer a source for continual discovery. My final advice to anyone looking to make comics: dive in and see where it takes you!

Notes

- Sketching Entropy: http://spinweaveandcut.com/sketching-entropy/. [^]

- Hexagonal compositions: http://spinweaveandcut.com/hexagonal-compositions/. [^]

- Circular compositions: http://spinweaveandcut.com/hexagonal-compositions/. [^]

- Ninjak https://pulidooninjak.blogspot.com/2021/07/on-ninjak.html. [^]

- The Rabbit page: https://spinweaveandcut.com/rocky-mt-comics-conference-and-rabbits-at-glc/. [^]

- The ‘rose’ page from Unflatttening: https://spinweaveandcut.com/rscon5-visualizing-references-and-behind-the-scenes-sketches/. [^]

Author’s Note

The images included in this article are copyright © Nick Sousanis and shared under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

Editors’ Note

This article is part of the Rapid Responses: Comics in and of The Moment Special Collection, edited by Jeanette D’Arcy and Kay Sohini, with Ernesto Priego and Peter Wilkins.

Competing Interests

The author is on the editorial team of The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship. Nick Sousanis is an external examiner on the author’s PhD dissertation committee.

References

Bechdel, A. (2021). The Secret To Superhuman Strength. S.L.: Mariner Books.

Gene Luen Yang (2020). Dragon hoops. New York: First Second.

Luen Yang, G. (2006). American Born Chinese. New York: First Second.

Madden, M. (2005). 99 Ways To Tell A Story: Exercises In Style. Chamberlain Bros.

McCloud, S. (1994). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. HarperCollins Publishers.

Monastersky, R. and Sousanis, N. (2015b). The Fragile Framework. Nature 527, 427–435 [online]. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1038/527427a

Moore, A. and Gebbie, M. (2002). This is Information. In: 9-11: Artists Respond. Dark Horse Comics, Chaos! Comics, and Image Comics.

Redondo, B. and Taylor, T. (2021). Nightwing. DC.

Sousanis, N. (n.d.). A Life in Comics: The Graphic Adventures of Karen Green. Columbia Magazine. [online] Available at: https://magazine.columbia.edu/article/life-comics-graphic-adventures-karen-green. [Accessed 21 Mar. 2022]

Sousanis, N. (n.d.). Security. [Comics] Available at: https://spinweaveandcut.com/security/ [Accessed 21 Mar. 2022].

Sousanis, N. (2004). Show of Hands. [Comics] Available at: https://spinweaveandcut.com/show-of-hands/ [Accessed 21 Mar. 2022].

Sousanis, N. (2011). Mind the Gaps. In: On Narrative Inquiry: Approaches to Language and Literacy. [online] Teachers College Press. Available at: https://spinweaveandcut.com/in-print-mind-the-gaps/ [Accessed 21 Mar. 2022].

Sousanis, N. (2015). Grids and Gestures: A Comics Making Exercise. SANE journal: Sequential Art Narrative in Education [online], 2(1). Available at: http://spinweaveandcut.com/grids-gestures/ [Accessed 21 Mar. 2022].

Sousanis, N. (2015a). Against the Flow. The Boston Globe [online]. 4 Oct. Available at: https://spinweaveandcut.com/sketching-entropy/ [Accessed 21 Mar. 2022].

Sue DeConnick, K. and Jimenez, P. (2021). Wonder Woman Historia: The Amazons. DC.