Introduction

The Batman villain Two-Face and François Rabelais’ Bridlegoose in The Third Book of Pantagruel ([1546] 1894) are identified with the law – or at least, the law distorted, exaggerated, caricatured. Two-Face decides matters based on the tossing of a double-faced coin, one side of which is defaced; in some respects, he is the successor to Rabelais’ Judge Bridlegoose, who decides the judicial cases before him by a throw of the dice. They both surrender their decision-making to the aleatory, in a manner that prompts us to gaze upon (or askance at) the [im]possible moment of decision. In the Judge Bridlegoose episode, the old Judge is on trial for his decision in a particular case, where his customary method of deciding cases by dice comes in for some discussion. Harvey Dent is also associated with the courtroom, and when he transforms into Two-Face, his obsessive decision-making still retains some ‘legal’ – even judicial – associations, even in its wild arbitrariness. This article takes a literary approach to the philosophy of law. The comparative approach draws out how these two characters illuminate broader questions of law and justice, through considerations of parody, satire, deconstruction, and play.

Mythical Origins and Mystique

Johan Huizinga remarks the play-like aspect of the adversarial system (from the contest to the wager) for resolving disputes in law:

Would it not be truer to say that the pronouncing of judgement (and hence legal justice itself) and trial by ordeal both have their roots in agonistic decision, where the outcome of the contest – whether by lots, chance, or a trial of some kind (strength, endurance, etc.) – speaks the final word? (Huizinga 1971: 82)

These processes belong to the category of ‘irrational’ decision-making (see William Twining, 2006: 35-61). Huizinga sees this resolution by contest or wager as pointing to ‘an affinity […] between law and play’ (Huizinga 1971: 76) that is embedded in law’s cultural origins. Rabelais’ Bridlegoose (whose decisions are based on the dice) indeed views the studious perusal of documents and evidence – which only impact his decisions insofar as their quantity affects his choice of dice – as comparable to recreational play, and therefore ‘healthful’. The consequences may however be grievous for the parties to the lawsuit/trial. While law would seem to require fixity (with ‘etymological foundation[s]’ that refer to ‘fixing’, ‘establishing’, etc2), Two-Face’s literally-flippant decision-making (by coin toss) seems likewise trivialising, but also somehow earnest and certainly consequential – indeed, it often instigates violent outcomes.

The suspicion of arbitrariness and/or unjustifiability strikes at the very heart of law – in the obfuscation of a violence in/of its originary myth, that is its violence in claiming/seizing its own justification and force, rooted in mystique – grounded in groundlessness, as Jacques Derrida (1990) notes. The origin would elude – in a bound that is also a bond, a binding; requiring of us a leap of faith. Peter Goodrich, discussing the literary in the legal, comments on the theological ‘foundational narrative’ and its ‘mythic’ connection to the ‘law of nature’:

The foundational narrative has to be one of necessity and as nothing human is of itself a necessity, authority and justification of the legal system lie in a mythic recourse to the law of nature as divine writ evidenced by the nomos of earth, here [giving the example of English common law] meaning the patterns and usages that persist and become the fictive figures of people and nation. (Goodrich 2021: 30)

Foundational narratives confer a certain force, becoming inextricable from the ‘founding’ moment itself (indeed, participating in the ‘founding’). Derrida comments on the ‘very moment of foundation or institution’ of law that attempts to justify itself, as being ‘a coup de force, of a performative and therefore interpretative violence that in itself is neither just nor unjust’ (Derrida 1990: 491–3) for there is no law or justice anterior to it to ground it: ‘Since the origin of authority, the foundation or ground, the position of the law can’t by definition rest on anything but themselves, they are themselves a violence without ground’ (493). The origin is a ‘mystical limit’ (493). Huizinga’s theory of the origin of law-as-play also posits it as anterior to justifying principles, such as ‘right’ and ‘wrong’; while play is not at odds with gravity for Huizinga, the idea of law-as-play goes some way towards un-fixing the moment that seeks to establish foundation.

Authorisation from a higher source would, in this view, be part of the retroactive mythicisation of origin. Huizinga cites biblical and classical antecedents to show that the distinction between ‘fate’, ‘Divine Will’, and ‘chance’ was blurred (1971: 79). He refers us to the etymology of the word ‘ordeal’ (through German), connecting it to ‘nothing more nor less than divine judgement’ (1971: 81). Bridlegoose’s judgements seem to defy mere probability. In Rabelais’ The Third Book of Pantagruel, Panurge expresses incredulity at Bridlegoose’s run of success/luck; Epistemon agrees that ‘[i]n good sooth, such a perpetuity of good luck is to be wondered at’ (3.XLIII). Pantagruel, in pronouncing judgement in Bridlegoose’s favour, seems to perceive the hand of God in Bridlegoose’s aleatory judicial decisions – a higher authority driving his agency through the vested authority of the court and re-confirmed on appeal by the ‘sovereign court’:

Truly, it seemeth unto me, that in the whole series of Bridlegoose’s juridical decrees there hath been I know not what of extraordinary savouring of the unspeakable benignity of God, that all those his preceding sentences, awards, and judgments, have been confirmed and approved of by yourselves in this your own venerable and sovereign court. (3.XLIII)3

Pantagruel suggests that the heavens are favourably disposed towards Bridlegoose because they have ‘contemplated the pure simplicity and sincere unfeignedness of Judge Bridlegoose in the acknowledgment of his inabilities’, and hence ‘did regulate that for him by chance which by the profoundest act of his maturest deliberation he was not able to reach unto’ (3.XLIV). Chance as divine guidance comes to patch up the trusting judge’s deficiencies. Conversely, Two-Face’s surrender to chance seems to spring from disillusionment and a loss of faith – tragically disillusioned, Two-Face resolves on this method of deciding matters by refusing conventional justification – because, ‘why not…’? (Finger, Kane, Robinson, and Roussos 1942: 4). Yet the deferral of decision to the coin also suggests deference to the coin’s ‘authority’ and reliance on this externalised decision-making process, alongside the oft-expressed cynicism of the villain.

Decision and the Incalculable

While Huizinga locates the roots of the adversarial approach in the ‘irrationality’ of the ‘contest’ (Huizinga 1971: 76) – ‘that is to say, in and by play’ with ‘the idea of divine judgement in the matter of abstract right and wrong’ arriving on the scene later (Huizinga 1971: 86–7) – both Bridlegoose and Two-Face take a leap into what is ‘beyond’ reason and beyond even the adversarial, suggesting a more ‘mystical’ violence that falls and intervenes from above, with the fall of the dice or coin.

The moment of decision partakes of the vertiginous [im]possibility of origination. Derrida notes that decision entails the encounter between calculation and the incalculable, taking a bound beyond guarantee:

Law is the element of calculation, and it is just that there be law, but justice is incalculable, it requires us to calculate with the incalculable; and aporetic experiences are the experiences, as improbable as they are necessary, of justice, that is to say of moments in which the decision between just and unjust is never insured by a rule. (Derrida 1990: 497)

Just judicial decisions do not merely ‘follow’ law ‘but must also assume it, approve it, confirm its value, by a reinstituting act of interpretation, as if ultimately nothing previously existed of the law, as if the judge himself invented the law in every case.’ Even in ‘conform[ing] to a preexisting law’, judgement constitutes a ‘responsible interpretation’ that does more than conserve the law:

In short, for a decision to be just and responsible, it must, in its proper moment if there is one, be both regulated and without regulation: it must conserve the law and also destroy it or suspend it enough to have to reinvent it in each case, rejustify it, at least reinvent it in the reaffirmation and the new and free confirmation of its principle. (Derrida 1990: 961)

In this view, the judge must be more than ‘a calculating machine’ (961); whereas on the other hand abandoning the law-as-rules and relying solely on her own interpretation, or else refraining from decision, is also not sufficient for a ‘just’ decision. This results in a paradox (a ‘double bind’), where justice is deferred:

It follows from this paradox that there is never a moment that we can say in the present that a decision is just (that is, free and responsible), or that someone is a just man – even less, ‘I am just.’ Instead of ‘just,’ we could say legal or legitimate, in conformity with a state of law, with the rules and conventions that authorize calculation but whose founding origin only defers the problem of justice. For in the founding of law or in its institution, the same problem of justice will have been posed and violently resolved, that is to say buried, dissimulated, repressed. (Derrida 1990: 961–3)

A just decision as law is ‘a decision that cuts, that divides’ – a decision that contains the possibility of radical divergence along with conservation: ‘A decision that didn’t go through the ordeal of the undecidable would not be a free decision, it would only be the programmable application or unfolding of a calculable process’ (Derrida 1990: 963). Both Bridlegoose’s and Two-Face’s methods would appear to embrace the incalculable, in a parodically literalised and paradoxically [ir]responsible fashion.

The satirical parody touches upon central principles of law, justice, and faith. Their decisions come to rest upon a balance of probabilities. Here, it is worth noting (as Twining [2006: 104] also reminds us) that legal verdicts fall short of absolute certainty: with the high threshold of ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ applying in criminal cases and the lower standard of ‘balance of probabilities’ in civil cases. Therefore, despite their refusal to even pretend to follow a grounding principle or value, the difference from regular practice that we witness in Bridlegoose’s and Two-Face’s decision-making may arguably be a difference in degree rather than in kind.

Pantagruel argues that Bridlegoose is fairer than his peers, because he is free from bias. Chance is divine, while the workings of law on the other hand are infiltrated by the self-interested and devilish practices of ‘the perverse advocates, bribing judges, law-monging attorneys, prevaricating counsellors, and other such-like law-wresting members of a court of justice, [who] turn by those means black to white, green to grey, and what is straight to a crooked ply’ (3.XLIV). Pantagruel laments the deficiencies of the law, its ‘unhallowed sentences and horrible decrees’, sources and authorities, and its tendency to sell itself to the highest bidder (3.XLIV).

The game of chance ostensibly ‘levels’ the ‘playing’ field of justice, in a manner that aspires to (and somewhat exceeds or overleaps) the principle of according the parties ‘equality of arms’, as well as that of ensuring the impartiality of the third-party adjudicator.4 It is a twisted parody of the figure of Blind Justice (Huizinga [1971: 79–80] suggests that the scales of justice were originally meant for weighing chances – an ‘oracle of lot’, ‘the emblem of uncertain chance, which is “in the balance”’). Where we would expect reasoned decisions, both Bridlegoose and Two-Face dispense with these. Twining notes that while Bridlegoose offers no justification for his methods (and is moreover not compelled to), a possible justification may be inferred, in that Bridlegoose’s methods are likely to be probabilistically right half the time, with Rabelais thus providing a critical contrast to the orthodoxy:

over the long run it was statistically highly probable that he would get the right result in about half the cases, whereas given the arbitrary confusion of the Pandects, the obfuscations and chicaneries of lawyers and the possibility of his own fallibility or corruption, there was no such guarantee that he would achieve this level of justice by purporting to decide on the merits. (Twining 2006: 126)

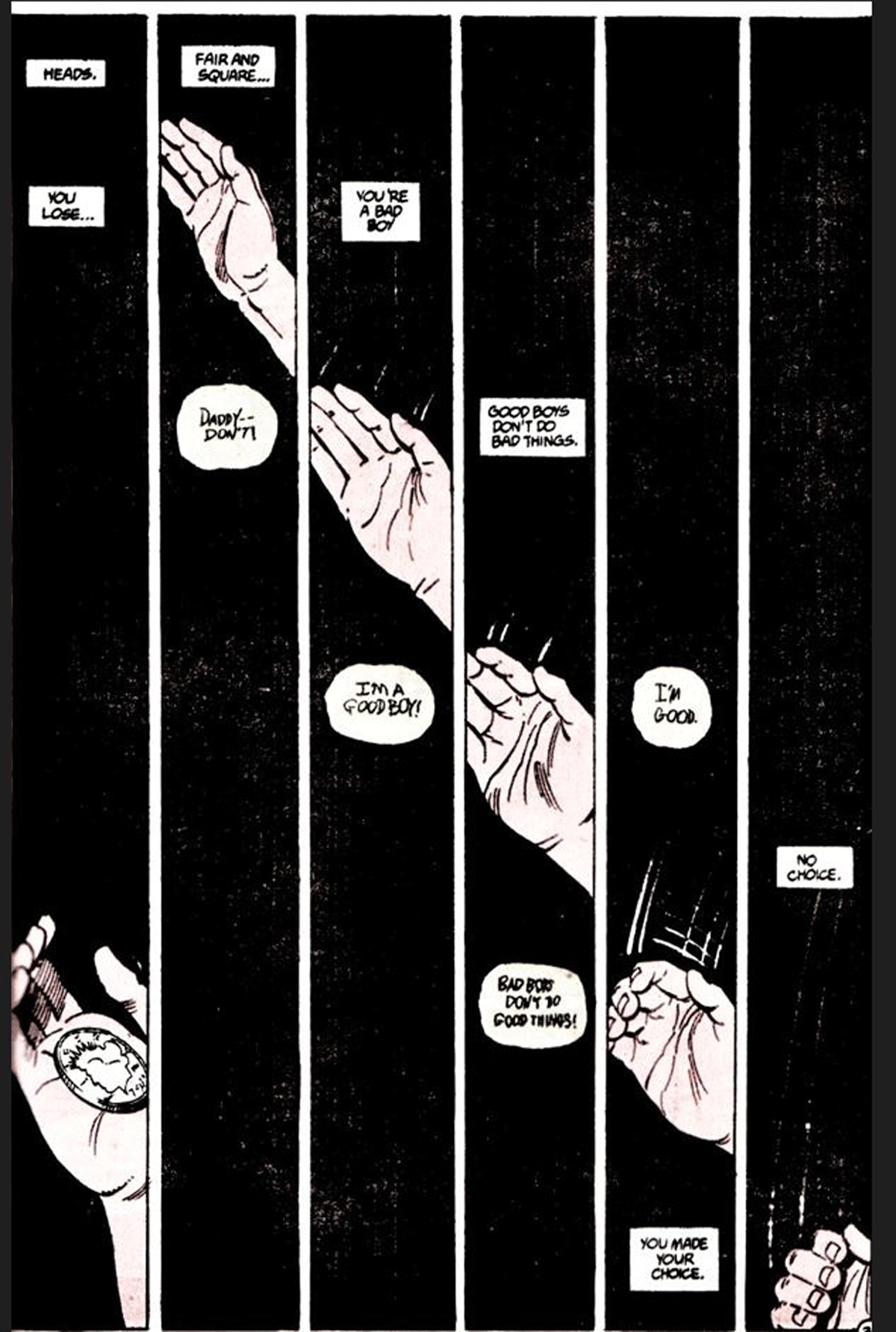

Two-Face comics show us one particularly abusive and corrupt alternative to Two-Face’s approach, in Harvey Dent’s father’s strategy of deciding whether his son deserves punishment in The Eye of the Beholder (Helfer, Sprouse, and Mitchell 1990). In contrast to Two-Face’s double-faced coin (one side of which is defaced), the two faces of the father’s coin are equivalent and the result is rigged, towards the attempted imposition of a terrible certainty. Harvey’s father always assigns ‘tails’ to his son, though unbeknownst to the young Harvey, the outcome is heads-or-heads. Harvey’s chance of obtaining a positive outcome is therefore almost nil – almost, because there is always the (albeit less probable) possibility that a flipped coin will not settle: for example in the punch-line ending to Detective Comics #66, Harvey’s coin lands on its edge in a crack in the floorboards (Finger, Kane, Robinson, and Roussos 1942: 13). Two-Face’s pre-origin story as Harvey Dent (the origin anterior to the disfigurement that births ‘Two-Face’) is thus overshadowed by a dominating and violently unreasonable Name of the Father (see Lacan 1993), where the roles of legislator, prosecutor, judge and punisher are, moreover, not distinguished; nor is ‘good’ distinguished from ‘bad’ (Helfer, Sprouse, and Mitchell 1990: 31). In the repeated comic panel sequences (e.g. Helfer, Sprouse, and Mitchell 1990: 2, 22, 31), while the tossed coin and punishing hand move obliquely through the black otherwise-featureless space, the panels are strictly vertical – indicating the domineering (somewhat phallic) verticality of the power relation (see Figure 1).5 Indeed, they suggest nothing less than the bars of a prison cell. The tyranny of law is here vested in a symbol (the father’s coin) that aspires to be the be-all-and-end-all, the final word and determination, yet deciding in advance – militating against the incalculable, attempting to close itself off to chance. In this version of the story, the father’s coin is passed on to Harvey and one side (the ‘bad’ side) defaced only later. The traumatised Two-Face repeats the ritual – with a difference, embracing wild chance.

The game of chance would appear to be equally unreasonable. However, the balance of probabilities would seem to invite a mathematicising approach. In another sense therefore, the game of chance is the reductio ad absurdum of a mathematicising probabilistic approach to logic, which also characterises the methods of some strands of the rationalist school. The gamification of probabilities in the two literary case studies analysed here calculates for the incalculable; yet the approach is unpinned from utilitarian and/or value-laden rationalist approaches to law (such as those approaches in the Benthamite tradition, where calculation is proposed as a base for legislation, as in the ‘moral thermometer […] which should exhibit every degree of happiness and suffering’ [Bentham 1843]). The extremes meet, as noted in a somewhat deconstructionist move by Twining:

[Bridlegoose] has revealed that of all the varied types of potential sceptics and relativists that we have considered, it is the most enthusiastic rationalists who are the nearest, among writers on law, to a genuinely sceptical position [vis-à-vis rationalism]. (Twining 2006: 130)6

In this grotesque (distorted yet in some ways distilled) form, it mounts a challenge through parody. The reductio to a single mechanism moreover allows for variations. Bridlegoose has his ‘little small dice’ for cases where ‘many bags’ are stacked on both sides; and ‘large great dice’ for when there are ‘fewer bags’, and the matter is therefore assumed to be simpler (3.XXXIX). We witness the mechanism’s exaggeration ad absurdum in Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth (Morrison and McKean 1989), where the therapy Two-Face is subjected to at Arkham Asylum takes the form of mathematicising and multiplying possibilities (‘we’ve successfully tackled Harvey’s obsession with duality’) ad absurdum: from the two-sided coin, to the six-sided die, to the seventy-eight possibilities of the tarot deck (‘next, we plan to introduce him to the I-Ching’). This increase in possibilities, supposed to wean him off his dependence on his coin, instead ends up cruelly immobilising his ability to make decisions – the therapy is in effect indistinguishable from punishment, devised to match and outdo the crime.

Parody as critique

Both Bridlegoose and Two-Face offer a satirical parody of law, which enables the critique outlined above. By ‘laying bare’ devices (Shklovsky [1921] 1990) of decision and adhering excessively to certain rules of procedure even as these are detached from their assumed principles, Bridlegoose and Two-Face’s ‘violations’ show up certain ‘fundamental’ similarities with the law itself, through contrast, isolation of elements, exaggeration – ‘fundamental’ here pointing to paradoxical foundations. Bridlegoose acknowledges the place of formality in conferring ‘force’ on judicial decisions – Bridlegoose hence follows certain conventions ritualistically, such as delaying judgement and perusing the evidence, though these tactics ultimately have no impact on the decisions he makes for one side or the other. However, this is not to say they serve no purpose whatsoever, for their impact is to render his decisions authoritative and official: ‘First, for formality sake, the omission whereof, that it maketh all, whatever is done, to be of no force nor value, is excellently well proved, by Spec. 1. tit. de instr. edit. et tit. de rescript. praesent’ (3.XL). Bridlegoose moreover acknowledges that it is in the nature of formality to sometimes trump substance: ‘oftentimes, in judicial proceedings, the formalities utterly destroy the materialities and substances of the causes and matters agitated; for Forma mutata, mutatur substantia’ (3.XL). This feature of procedure, he notes – appealing to the shared experience of his fellow-judges trying his case – ‘is not unknown to you, who have had many more experiments thereof than I.’ We are reminded of the farcically bloated procedure in the fictional case Jarndyce v. Jarndyce in Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, which only ends (with bouts of laughter) when the disputed inheritance has all been ‘absorbed in costs’ ([1853] 1996: 975).

Bridlegoose’s own attitude is accepting rather than critical, as if he has been ‘initiated’ into the bare game without adopting its associated values (in that context, such ‘values’ have been at any rate corrupted). Huizinga, commenting on the origins of justice as a ‘game’, draws attention to the ‘rules of the game’, with decisions deriving their determining force (‘incontrovertibility’) from these rules, even where these rules create an opening for luck and chance: ‘Justice is made subservient – and quite sincerely – to the rules of the game. We still acknowledge the incontrovertibility of such decisions when, failing to make up our minds, we resort to drawing lots or “tossing up”’ (1971: 79). This excessive formalism, literalism, and unfailing adherence to the rules even where they seem to serve no function other than the circular one of upholding the rules themselves is seen as key to Rabelais’ parody of law by Mikhail Bakhtin:

The legal term alea judiciorum (meaning the arbitrariness of court decisions) was understood by the judge literally, since alea means ‘dice.’ Basing himself on this metaphor, he was fully convinced that since he pronounced his judgments by dicing, he was acting in strict accordance with legal requirements. […] Thus all the cases judged by Bridlegoose are transformed into a gay parody, with the dice as the central image. (Bakhtin [1965] 1984: 238)

The rules for both Bridlegoose and Two-Face are rigidly and ritualistically there but ungrounded, detached from a justificatory framework. It is noteworthy that this procedural correctness, even when shown to be without ground or real purpose, is nonetheless a founding element in establishing the weight and authority of judgement (in Bridlegoose’s case), accompanied by more overt violence in Two-Face’s approach.

Parody has the ability to reveal something about the form more generally, in relation to typicality (Shklovsky [1921] 1990: 170). Bridlegoose makes repeated reference to the proximity of his own practice with the general practice in law:

which your worships do, as well as I, use, in this glorious sovereign court of yours. So do all other righteous judges in their decision of processes and final determination of legal differences […] Mark, that chance and fortune are good, honest, profitable, and necessary for ending of and putting a final closure to dissensions and debates in suits at law. (3.XXXIX)

Bridlegoose clearly believes he is ‘in obedience to the law’ and continually backs this up with references to weighty authorities and dresses them in Latin for further effect. Like Harvey Dent/Two-Face, who was first of all a prosecutor and District Attorney (then dons the robes of a judge during the events of No Man’s Land [Rucka and Teran 1999]), Bridlegoose bears a close association with the authority of law itself, becoming almost identified with it. Pantagruel draws attention to Bridlegoose’s long career as a judge – despite his apparently idiosyncratic methods, Bridlegoose is perfectly at home in the courts, and his ‘evenly balanced’ approach comes in for commendation: ‘his demeanours, for these forty years and upwards that he hath been a judge, having been so evenly balanced in the scales of uprightness’ (3.XLIII). It is worth noting that while Bridlegoose’s methods are questioned, they are not on trial – only his decision in a particular case is under review, and Bridlegoose’s defence is that his eyesight has dimmed with age and he mistook the dice. As Twining notes, ‘It is significant that at his trial Judge Bridlegoose felt no need, and was not asked, to justify his method of decision’ (Twining 2006: 126).

This stripping away of associated values and goals brings us close to Huizinga’s theory that at its source, ‘the ethical-juridical conception, comes to be overshadowed by the idea of winning and losing, that is, the purely agonistic conception’, which results in the foregrounding of the ‘element of chance’ (Huizinga 1971: 78); this is capable of being re-cast as a contest of unequal odds, such as a strength-based trial. Strength is an obviously arbitrarily selected criterion. However, this line of thought may lead us to the perhaps unsettling recognition that ‘there may be non-logical elements, even random processes, affecting the reasoning and choices of the decision-maker’, to be found even in ‘lawful decision-making’ (Robert French 2017: 603). Furthermore, the caricature of the ‘Hard-nosed Practitioner’ type as critically depicted by Twining (2006: 105), though an exaggeration, suggests that we cannot easily dismiss the continuing persistence of an attitude to law and legal practice stemming from the idea that the lawyer’s aim is to win a case, rather than to achieve justice through reason, and the perception that the adversarial trial is therefore, when everything else is stripped away, a ‘game’ at its core.

Two Faces of the Beast and the Law

When Bridlegoose is himself put on trial, he comes to occupy two roles that cannot be seamlessly reconciled. He appears as the accused before others called upon to judge him; yet he still appears as a judge and what is at issue is his judgement (one in particular, rather than his methods; though these are discussed). By making reference to the practices of the ‘sovereign court’ (that he claims to share) to support his defence, Bridlegoose stands before the court as a judge to be judged; by summoning the authority of the law in his defence, he comes to reflect and represent the law itself, put on trial.

Two-Face’s identity is invested in, and bound to, the two (connected-yet-heterogeneous) faces of his coin – ‘how about a man who staked his soul, his very actions on the spinning of a silver coin?… Because he was like that coin itself! He too had two sides…’ (Finger, Kane, Robinson, and Roussos 1942: 1). Similarly, prior to becoming Two-Face, he staked everything on the law: ‘The law is my life. It keeps me whole, maybe even keeps me sane’ (Helfer, Sprouse, and Mitchell 1990: 26; emphasis added). A paradox tears through Two-Face, in his inability to reconcile, or maintain total separation between, his various aspects in the trial of Jim Gordon (Rucka, Scott and Floyd, 1999) during the events of No Man’s Land, where he performs the functions of prosecutor, judge, and defense lawyer. In No Man’s Land, Gotham has been evacuated and the city is segregated from the rest of the world in a prolonged state of emergency, left to its own devices as it picks up the pieces in the aftermath of an earthquake. Staking out his territory, Two-Face rather conspicuously comes to stand for judgement when the orthodox order is suspended; while Gordon’s ‘Blue Boys’ in a different territory still try to represent and carry out law enforcement (though a faction within this, usurping and perverting the ‘rule of law’, turns towards methods that are increasingly fascistic and ruthless).

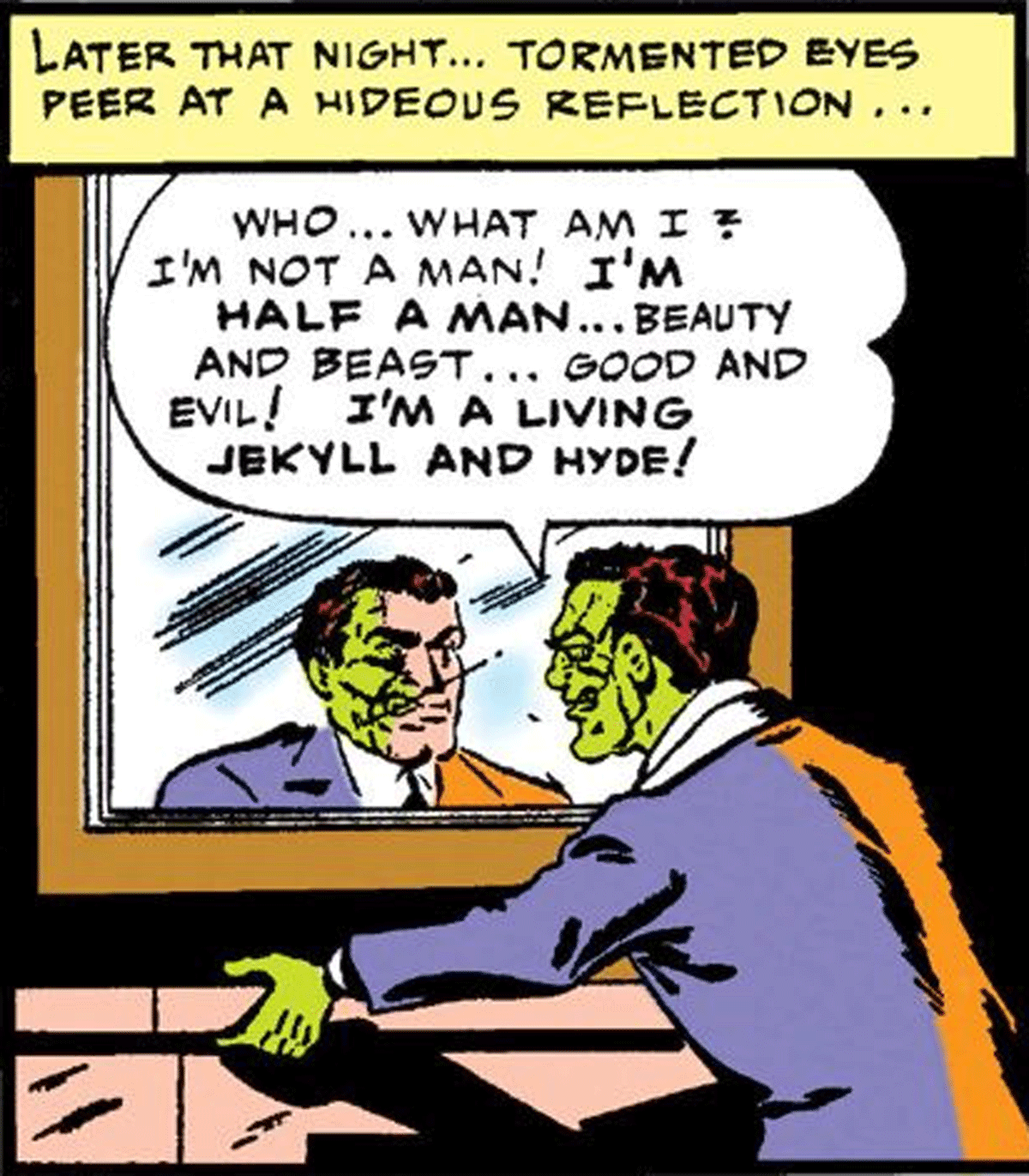

When introduced and initially disfigured, in Detective Comics #66 ‘Batman: The Crimes of Two-Face’ (Finger, Kane, Robinson, and Roussos 1942: 4), Harvey Kent (later ‘Dent’) exclaims before his reflection in a mirror: ‘Who… What am I? I’m not a man! I’m half a man… Beauty and beast… Good and evil! I’m a living Jekyll and Hyde!’ (Figure 2). The seeming opposition between the ‘beast’ as ‘other’ and ‘a sovereignty that is most often represented as human or divine, [is] in truth anthropo-theological’ (Derrida [2001] 2009: 14). The opposition masks a proximity. Criminal, beast, and sovereign share a ‘common being-outside-the-law’ and ‘a troubling resemblance’, a reminder too of the violence of the sovereign (the maker of law and the law itself):

they call on each other and recall each other, from one to the other; there is between sovereign, criminal, and beast a sort of obscure and fascinating complicity, or even a worrying mutual attraction, a worrying familiarity, an unheimlich, uncanny reciprocal haunting. (Derrida [2001] 2009: 17)

In the ‘Trial’ episode (1994) of Batman: The Animated Series, Joker is Judge, Two-Face is prosecutor, and Batman is the accused, charged with creating his villains. As an unofficial supplement to law, Batman is charged with generating new types of criminality. Though the verdict eventually rendered is that of innocence, some intriguing questions have been asked that stay with the viewer. Batman, as a rogue figure for justice, stands both within and outside the law – like the sovereign and the criminal; and indeed as his animal namesake implies, already a hybrid. As such, the villains tell us something about their hero opponents, and both villains and heroes tell us something about the system that co-produces them. The very power of law borne by the sovereign, who can make as well as suspend laws, is also that which marks the sovereign out as ‘brutal’, on a threshold, both in-and-out – double-faced and double-facing:

this arbitrary suspension or rupture of right […] runs the risk of making the sovereign look like the most brutal beast […] as though both of them were situated by definition at a distance from or above the laws, in nonrespect for the absolute law, the absolute law that they make or that they are but that they do not have to respect. Being-outside-the-law can, no doubt, on the one hand (and this is the figure of sovereignty), take the form of being-above-the-laws, and therefore take the form of the Law itself, of the origin of laws, the guarantor of laws, as though the Law, with a capital L, the condition of the law, were before, above, and therefore outside the law, external or even heterogeneous to the law; but being-outside-the-law can also, on the other hand (and this is the figure of what is most often understood by animality or bestiality), [being-outside-the-law can also] situate the place where the law does not appear, or is not respected, or gets violated. (Derrida [2001] 2009: 17)

Two-Face stands on that threshold, dis-figuring law itself, in his usurpation of its sovereign-bestial authority – making visible its ‘other’ side. The coin, like metaphor, is a currency of exchange, something put into circulation, destined to be replaceable – yet, in another theory of the origin of law, this exchange is the shifting ground for law itself: Friedrich Nietzsche traces the origins of law as calculation and of the fictional equivalence (jus talionis) between crime and punishment – shaping the individual’s relation with[in] law as subject – back to commerce and exchange, credit and debt (Nietzsche [1887] 2007: 39-40): ‘This would mean, in sum, that what makes us believe, credulous as we are, what makes us believe in an equivalence between crime and punishment, at bottom, is belief itself; it is the fiduciary phenomenon of credit or faith’ (Derrida [2000] 2014: 152).

The defacing of a coin was historically taken (with counterfeiting) as a sign of contempt of authority; it constituted a grievous offence tantamount to high treason, since it seemed to extend further than simply ‘offending’ authority. It seemed to stake a claim to the sovereign seat of authority itself, to authorise itself by usurping the ‘legitimate’ source of law. In England, in the ‘long eighteenth century’:

Defacing the image of a monarch, and attacking what is legally described as ‘the King’s Currency’, had significant political connotations with severe outcomes – an individual found guilty of these crimes would be hanged, drawn and quartered if male, and strangled and burned if female. (Robert S. Rock 2014)7

In practice, the punishment was usually hanging – no less a violent display of authority, surrounded by ceremony (Wennerlind 2004: 148). Law, at this boundary, shows itself at its most brutally violent in the force brought to bear to reassert its monopolising claim to authority and violence (Derrida [2000] 2017: 35) – a monopoly that, from his double-facing split/threshold position, Two-Face both challenges and reinforces. The criminal Two-Face seizes the force of law on semi-authorised grounds, by virtue of his professional career; he [illegimately] claims from this an absolute authority, at least as an agent for the deferred authority of chance. He thereby raises a challenge to (and reveals) the violence inherent in the legal system itself – making it sometimes difficult to distinguish between illegitimate and legitimate (or legitimating) violence.

This is a distinction hero-vigilantism likewise troubles. Thematically, superhero comics tend to engage directly with questions of law, order, and justification of force (see Bradford W. Reyns and Billy Henson 2010 for a quantitative approach), in a way that shows both critical difference and troubling similarity. Superhero-vigilante justice evades accountability at law – it seems to derive its ‘justification’ from supplementing inadequacies and inefficiencies within the legal system:

The nature of justice and the thorny relation of vigilante justice and violence to law have become central themes in the superhero genre. Superhero-vigilante justice is unauthorized by the legal structure, and unaccountable to it—it seems to seize its own justification in dealing with the inadequacies, inefficiencies, and overspill of official law enforcement and judicial systems, finding its raison d’être in supplementing existing deficiencies. (Bonello Rutter Giappone and Turner 2017: 48)

While Harvey Dent’s starting arena is the courtroom, Batman – The Eye of the Beholder suggests – is an outsider in that legal environment. Batman gives us his critical perspective on what goes on in the courtroom, seeing it as a kind of circus comedy, starring ‘the clowns of justice and the jugglers of truth’ (Helfer, Sprouse, and Mitchell 1990: 12). As such, superheroes can tell us something about these deficiencies in law and the legal system, in a manner that is again reminiscent of Bridlegoose (who works from within the legal system, but also in some crucial ways marks his difference):

Rabelais was specifically concerned to satirize the minutiae of the Pandects as well as the more familiar targets of the chicaneries of lawyers and the defects of legal procedures. But Judge Bridlegoose is sometimes interpreted as throwing down a broader challenge to the law – to do better than the dice, that is to get correct results in more cases than could be obtained by chance. (Twining 2006: 125)

At a further remove as (typically) a villain,8 what Two-Face – as a juggler of law – provides is a challenge to systems of law but also to Batman’s own values of justice, as detective-vigilante who works closely with Police Commissioner Jim Gordon (often joining forces against corrupt law enforcement in Gotham)9 – raising further fundamental and uncomfortable questions about law, justice, violence for Batman to contend with.

Conclusion

Thomas Giddens (2015: 8-15) highlights the shared foundations of comics and law in logic and reason, but also the limitations/inadequacy of logic and reason, which Giddens suggests comics are well-placed to demonstrate – the formalisation and framing through the ‘rational grid’ do not quite contain the image, but channel it multi-directionally, as affect, sensory appeal, context, etc spill over10 (see also: Goodrich on the image in law, 2021: 82-3). This is reminiscent of the Rabelaisian carnivalesque according to Bakhtin ([1965] 1984: 52, 420), that troubles and challenges the ‘static’ character of ‘official’ neatly ordered strict boundaries.

Parody in any medium tends to exceed or bend the frame even as it reflects (unflatteringly) the parodied form. Excessive formalism reveals its own in-built fault – a tendency towards irrationality; excessive rigidity is liable to be betrayed by its own inelasticity (Bergson [1900] 1980). Distortion and the grotesque are associated with satirical parody in the Bakhtinian sense, and both Bridlegoose and Two-Face offer grotesque caricatures. However, parody also defamiliarises (Shklovsky [1921] 1990) – its difference from the ‘original’ has the capacity to expose to our sight something in the ‘original’ and to destabilise our assumptions regarding it. In Detective Comics #66, Harvey/Two-Face encounters/confronts his split self in the mirror, prompting him to recast his view of his own identity and with it, his approach to his principles (including as a legal professional) – which thereafter veer into arbitrariness, anchored (rather, unfixed) by the flipping of a double-faced coin. The game of chance shows up arbitrariness haunting the process of calculation itself. As reflecting-distorting doubles of the law who (paradoxically) show no intention of abandoning the Law,11 Bridlegoose and Two-Face function as parodies;12 as parodies, they open up a space for critical distance (Hutcheon 1985), revealing the excesses already at work within the system itself, and inviting questions that go to the mythic core of law and its relation to justice, to law’s unstable self-justificatory grounds and foundational cracks, and to the very possibility of justice.

Notes

- Law and evidence scholar William Twining here discusses theoretical frameworks based on rationality and challenges to rationality in approaches to evidence and legal reasoning. [^]

- ‘The etymological foundation of most of the words which express the ideas of law and justice lies in the sphere of setting, fixing, establishing, stating, appointing, holding, ordering, choosing, dividing, binding, etc. All these ideas would seem to have little or no connection with, indeed to be opposed to, the semantic sphere which gives rise to the words for play. However, as we have observed all along, the sacredness and seriousness of an action by no means preclude its play-quality’ (Huizinga 1971: 76). [^]

- Richard Eggleston supports this ‘divine guidance’ interpretation (in Twining 2006: 156n156). [^]

- John Marshall Gest writes: ‘The method of Judge Bridlegoose indeed insures absolute judicial impartiality’ (Gest 1924: 409). [^]

- This could be said to be a moment where decision (albeit woefully over-determined) is suspended for a space. The unbearability of time – which we are prompted to read through the ‘linear’ (here: left to right) sequence, in Charles Hatfield’s terms (2009: 139–140, following Pierre Fresnault-Deruelle) – as the young Harvey’s fate hangs in the balance, is further stretched out by its tension with the page-length verticality of each panel. The verticality invites us to view the page ‘holistically’, yet the full picture is also denied us. Hatfield (140) suggests that such tensions pose a ‘challenge’ to the reader – and indeed, in this case (fittingly), the sequence is not so easy (or comfortable) to read. The coherence of the ‘moment’ is fractured, as the de-contextualised objects grotesquely dominate the space, occupying Harvey’s childhood fears and his recurring adult nightmares. This suspension is achieved through visual means that exploit a tension in the ‘relationship between perceived time and perceived space’, which Hatfield identifies as characteristic of comics, where ‘format’ (including page layout) is a ‘signifier in itself’ (144). [^]

- Twining observes that: ‘Interest in Bridlegoose has recently revived in connection with discussions about the potential uses and abuses of mathematical reasoning in legal processes’ (Twining 2006: 125). [^]

- On the American historical context, see Kenneth Scott (1957). [^]

- In the first comic to feature Two-Face and his origin story, the decision to become a (half-)criminal is also based on the toss of a coin (Finger, Kane, Robinson, and Roussos 1942: 4). The decision to do some good is likewise decided by the toss of a coin, for example in No Man’s Land (Rucka, Pearson, and Smith 1999). In effect, the defaced side of the coin does not suppress the non-criminal side – rather, it amplifies instability. As with Two-Face himself, there are two sides: the law is reduced to the coin; the coin is made to carry the weight of the law. [^]

- Scott Vollum and Cary D. Adkinson (2003: 101) observe that Batman ‘works outside the boundaries of the law and considers himself an arbiter of justice. Distrustful of law enforcement, Batman takes it upon himself to uphold justice and fight crime. While he often cooperates with law enforcement, he refuses to accept their boundaries as defining what is and is not just.’ Vollum and Adkinson, however, contrast Batman’s position with Superman’s, noting that the latter tends to appear more as an authorised upholder of law, American idealism, and the state, thus affirming these ‘sources’ of power (see also Reyns and Henson [2010] for a supporting view). However, it could be argued that the intervention of Superman – holding a power nearly invulnerable to challenge, and supposed to be ‘purer’ in ideals – also serves to show up the deficiencies of the law, both in terms of ineffectiveness and in terms of falling short of the ideal. Of course, such an implied purity of power without equal holds a terror of its own, and we are reminded of Derrida’s cautionary and trembling ‘Post-scriptum’ to ‘Force of Law’ (1990: 1040–1045), on the total devastation haunting the messianic vision of divine justice. Relatedly, Neal Curtis (2016: 7) gives the example of the super-powered Magog who, in his use of terrible ‘indiscriminate and extreme violence’, lacks Superman’s grounding values and aspires even beyond Superman’s self-imposed limits in the name of ‘justice’, leaving large-scale destruction in his wake. [^]

- For another discussion on the relationship between comics and law, including comics as critique of law, see Luis Gomez Romero and Ian Dahlman (2012). [^]

- Two-Face generally finds other ways to assert or use the law (through the law of chance); even when he resigns as District Attorney in the first Two-Face story, he resolves to use his legal knowledge as a criminal (Finger, Kane, Robinson, and Roussos 1942: 5). [^]

- On the double as parody, see Bakhtin [1963] 1984: 193–204. [^]

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the reviewers for their deeply engaged, generous, and thought-provoking feedback. Thanks too to Ivan Callus for his insightful comments on an earlier draft. I would also like to thank Ġorġ Mallia for kindly sharing his extensive comics resources with me; Samwel Mallia for his time; and David E. Zammit for his support. I am grateful to the editorial team for their efficiency and attention to detail.

Editorial Note

This article is a piece of research that underwent double blind peer review by two external reviewers, and it is part of the Graphic Justice Special Collection edited by Thomas Giddens and Ernesto Priego with support from the journal’s editorial team. Our gratitude to our pool of peer reviewers. Though the journal generally discourages the use of endnotes, the editors agreed to include them in this instance as they offer additional commentary and references that are useful but would have otherwise disrupted the main text. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material under educational fair use/dealing for the purpose and criticism and review and full attribution and copyright information has been provided in the captions.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Bakhtin, M 1963 Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics (trans. Caryl Emerson) 1984. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctt22727z1

Bakhtin, M 1965 Rabelais and His World (trans. Hélène Iswolsky) 1984. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Bentham, J 1843 Principles of the Civil Code. Available at: https://www.laits.utexas.edu/poltheory/bentham/pcc/pcc.pa01.c06.html Last accessed 10 August 2022.

Bergson, H 1900 Laughter. In: W. Sypher, ed. 1980. Comedy: ‘An Essay on Comedy’ by George Meredith, ‘Laughter’ by Henri Bergson. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. pp. 61–190.

Bonello Rutter Giappone, K and Turner, C 2017 How much Deadpool is too much Deadpool?. In: N. Michaud and J.T. May, eds. 2017. Deadpool and Philosophy: My Common Sense is Tingling. Chicago: Open Court. pp. 39–50.

Curtis, N 2016 Sovereignty and Superheroes. Manchester: Manchester University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7228/manchester/9780719085048.001.0001

Derrida, J 1990 Force de Loi: Le Fondement Mystique de l’Autorité. Cardozo Law Review, 11(5–6): 920–1046. Available at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/cdozo11&div=44&id=&page= Last accessed 19 November 2022.

Derrida J 1999–2000 The Death Penalty, Volume I (trans. Peggy Kamuf). Eds. G. Bennington, M. Crépon, and T. Dutoit. 2014. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Derrida, J 2000–1 The Death Penalty, Volume II (trans. E. Rottenberg). Eds. G. Bennington and M. Crépon. 2017. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Derrida, J 2001–2 The Beast and the Sovereign, vol. 1 (trans. G. Bennington). Eds.: M. Lisse, M-L. Mallet, and G. Michaud. 2009. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226144399.001.0001

Dickens, C 1853. Bleak House. 1996. London: Penguin Classics.

Finger, B (w), Kane, B (p), Robinson, J and Roussos, G (i) 1942 Batman: The Crimes of Two-Face. Detective Comics (Volume 1) #66 Aug. National Comics Publications [DC Comics].

French, R 2017 Judge Bridlegoose, Randomness and Rationality in Administrative Decision-Making. Monash University Law Review, 43(3): 591–604. Available at: https://bridges.monash.edu/articles/journal_contribution/Judge_Bridlegoose_Randomness_and_Rationality_in_Administrative_Decision-Making/10066049. Last accessed 19 November 2022.

Gest, JM 1924 The Trial of Judge Bridlegoose. American Law Review, 58(3): 402–421. Available at: https://heinonline-org.ejournals.um.edu.mt/HOL/Page?public=true&handle=hein.journals/amlr71&div=73&start_page=503&collection&collection=journals. Last accessed 19 November 2022.

Giddens, T 2015 Lex Comica: On Comics and Legal Theory. In: T. Giddens, ed. 2015. Graphic Justice: Intersections of Comics and Law. Oxon: Routledge. pp. 8–15. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315765754

Gomez Romero, L and Dahlman, I 2012 Introduction – Justice Framed: Law in comics and graphic novels. Law Text Culture, 16(1): 3–32. Available at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/2. Last accessed 19 November 2022.

Goodrich, P 2021 Advanced Introduction to Law and Literature. Cheltenham and MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Hatfield, C 2009 An Art of Tensions. In: J. Heer and K. Worcester eds. 2009. A Comics Studies Reader. Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. pp. 132–148.

Helfer, A (w), Sprouse, C (p), and Mitchell, S (i). The Eye of the Beholder. Batman Annual (Volume 1) #14 Jul. 1990 DC Comics.

Huizinga, J 1971 Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Hutcheon, L 1985 A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms. New York: Methuen.

Lacan, J 1993 The Psychoses 1955–1956: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book III (trans. Russell Grigg). Ed. Jacques-Alain Miller. New York and London: W.W. Norton and Company.

Morrison, G (w) and McKean, D (i) 1989 Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth. DC Comics.

Nietzsche, F 1887 On the Genealogy of Morality (trans. Carol Diethe). Ed. Keith Ansell-Pearson. 2007. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rabelais, F 1546 The Third Book of Pantagruel, in Gargantua and his Son Pantagruel, The Works of Rabelais (trans. Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty and Peter Antony Motteux). 1894. Derby: The Moray Press. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1200/1200-h/1200-h.htm. Last accessed 19 November 2022.

Reyns, BW and Henson, B 2010 Superhero Justice: The Depiction of Crime and Justice in Modern-Age Comic Books and Graphic Novels. Sociology of Crime, Law and Deviance, 14: 45–66. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1108/S1521-6136(2010)0000014006

Rock, RS 2014 Criminal Skill: The Counterfeiter’s Craft in the Long Eighteenth Century. Coins, Crime and History: A Numismatic and Social History of Counterfeiting. Available at: https://crimeandcoins.wordpress.com/2014/03/30/criminal-skill-the-counterfeiters-craft-in-the-long-eighteenth-century/ Last accessed 19 November 2022.

Rucka, G (w), Pearson, J (p), and Smith, C (i) 1999 Two Down Batman Chronicles (Volume 1) #16 March. DC Comics.

Rucka, G (w), Scott, D (p), and Floyd, J (i) 1999 Jurisprudence, Part II. Detective Comics (Volume 1) #739 Dec. DC Comics.

Rucka, G (w) and Teran, F (p, i) 1999 Mosaic, Part 2. Detective Comics (Volume 1) #732 May DC Comics.

Scott, K 1957 Counterfeiting in Colonial America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shklovsky, V 1921 The Novel as Parody: Sterne’s Tristram Shandy. In: Theory of Prose (trans. Benjamin Sher) 1990. Normal, IL: Dalkey Archive Press. pp. 147–170.

Trial 1994 Batman: The Animated Series. Fox Kids, May 16

Twining, W 2006 Rethinking Evidence: Exploratory Essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511617249

Vollum, S and Adkinson, CD 2003 The Portrayal of Crime and Justice in the Comic Book Superhero Mythos. Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 10 (2): 96–108. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b0ee82df793927c77add8b6/t/601080b4f2ec0d185a6a2af1/1611694260237/1+Vollum+2003.pdf. Last accessed 19 November 2022.

Wennerlind, C 2004 The Death Penalty as Monetary Policy: The Practice and Punishment of Monetary Crime, 1690–1830. History of Political Economy, 36 (1): 131–161. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1215/00182702-36-1-131